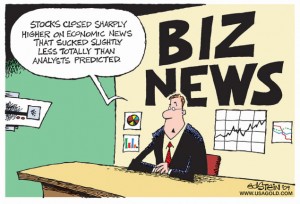

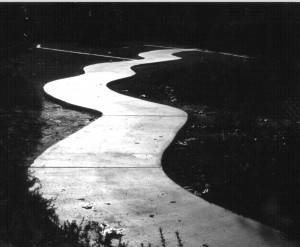

Career choices used to be simple. Go to school to be, say, a doctor, lawyer or reporter. Get your degree, apprentice as an intern, an associate or a budding Jimmy Olsen, and then ply your trade. In medicine or law you would make a lot of money and learn golf for when you retired at 55. But for growing numbers of us life rarely moves from point A to B anymore. Instead, we follow a long and winding road with some fascinating forks.

Career choices used to be simple. Go to school to be, say, a doctor, lawyer or reporter. Get your degree, apprentice as an intern, an associate or a budding Jimmy Olsen, and then ply your trade. In medicine or law you would make a lot of money and learn golf for when you retired at 55. But for growing numbers of us life rarely moves from point A to B anymore. Instead, we follow a long and winding road with some fascinating forks.

Consider Lynde McCormick, a colleague at the Rocky Mountain News in Denver in the 1980s. While working as a business reporter, Lynde wielded a deft touch with words. He had a sharp eye for big, broad stories and wrote weekly takeouts for a supplement we called Business Tuesday, doing packages the rest of us all wanted to do. Later, he rose to business editor, where — among other things — he waged war on adverbs. If it ended in an “ly,” he’d say, kill it. A Californian, he also had a weakness for fast cars and from time to time turned his hand to new car reviews.

Lynde’s career has taken some stunning turns since then. He left the Rocky for the bright lights at a TV channel the Christian Science Monitor experimented with and then joined Monitor Radio. An adventurer, he landed a job with CNBC in Hong Kong, a spot he loved. When CNBC pulled the plug in ’96 on its Hong Kong operation and merged with Dow Jones TV in Singapore, Lynde says, he moved back to Boston to serve as business editor at the Monitor’s newspaper. Meantime, his equally adventurous wife, Andrea, started a company that imported Chinese antique furniture.

Then things got interesting. After a couple of years, he joined her business. The pair drove around the country, towing a trailer and doing antiques shows, as many as three each month. Eight years ago, they opened a gallery in Manhattan, The Han Horse on Lexington Avenue, to market furniture from the late Qing Dynasty (1700-1900) and pottery artifacts from as long ago as 206 BC. They continue to run it, even though the antiques business has been a tough go in recent years.

Then things got interesting. After a couple of years, he joined her business. The pair drove around the country, towing a trailer and doing antiques shows, as many as three each month. Eight years ago, they opened a gallery in Manhattan, The Han Horse on Lexington Avenue, to market furniture from the late Qing Dynasty (1700-1900) and pottery artifacts from as long ago as 206 BC. They continue to run it, even though the antiques business has been a tough go in recent years.

By something of a back door, the McCormicks also got into the restaurant business. They backed a friend who opened a spot in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn and wound up running it when he ran into personal problems. The Brooklyn Label serves espresso drinks that Lynde says are “amazingly good.” It’s gotten some good notices from, for instance, New York Magazine.

As his career has unfolded, Lynde’s reporting skills have come in handy. “I have constantly tried to gather as much information as possible, going to expert sources, listening to what they had to say, and then using the parts that made sense for our restaurant,” he says. “It’s a lot like writing a story – you gather the best information possible and then use your own judgment and intelligence to figure out how to use it.”

He also has developed a good sense of marketing and customer service — which might be helpful for journalists. “With both businesses, our philosophy has been that when someone walks through the door, the goal is not to sell them something but to make them want to come back,” Lynde says. “The result is that people, generally, like us… which has a lot to do with why we are still in business.”

He also has developed a good sense of marketing and customer service — which might be helpful for journalists. “With both businesses, our philosophy has been that when someone walks through the door, the goal is not to sell them something but to make them want to come back,” Lynde says. “The result is that people, generally, like us… which has a lot to do with why we are still in business.”

Today, the Rocky is no more, a victim of the Internet and the great newspaper consolidation wave. The Monitor serves up its news coverage mostly online, a route many news outfits may wind up taking. And CNBC soldiers on. But the skills Lynde mastered at such places are helping him in ways he likely never imagined. I expect he has few regrets for the time he spent learning them.

For many journalists and journalism students, the road won’t be straight. But the views can make it damn interesting.