Should exponents of unpopular — but widely held — views get a forum on campus?

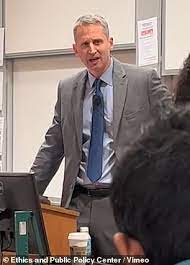

Princeton University Professor Robert P. George, 68, boasts a resume few could equal.

After earning degrees from Swarthmore, Harvard and Oxford, this grandson of immigrant coal miners from Morgantown, West Virginia, went on to chair the U.S. Commission on International Freedom. Earlier, he served on President George Bush’s Council on Bioethics and was a President Bill Clinton appointee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He has also served as the U.S. member of UNESCO’s World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (COMEST) and as a former Judicial Fellow at the Supreme Court of the United States.

His honors include the U.S. Presidential Citizens Medal, the Honorific Medal for the Defense of Human Rights of the Republic of Poland, the Canterbury Medal of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, the Sidney Hook Memorial Award of the National Association of Scholars, the Philip Merrill Award of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni, the Bradley Prize for Intellectual and Civic Achievement, the Irving Kristol Award of the American Enterprise Institute, the James Q. Wilson Award of the Association for the Study of Free Institutions, Princeton University’s President’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, and the Stanley N. Kelley, Jr. Teaching Award of the Department of Politics at Princeton.

Despite the fact that he is an outspoken conservative, he counts among his friends Harvard Prof. and noted liberal philosopher Cornel West. The two have appeared in venues together.

George seems like someone from whom students at Washington College might learn something.

But even when his subject was “Campus Illiberalism” – the trend of speakers being silenced because of views some find repugnant – he was shouted down at the small Maryland school on Sept. 7. As The Chronicle of Higher Education just reported, a small group of protesters entered the room, yelling and playing loud music. They ignored pleas for civility from the professor who invited George, Joseph Prud’homme, who heads the school’s Institute for Religion, Politics and Culture and who had earned his doctorate at Princeton.

Prud’homme led a silenced George out of the venue.

The Princeton prof’s cancellable offense: he has opposed same-sex marriage, abortion, and expansions of transgender rights. While he wasn’t slated to speak about those topics, per se, his very appearance was enough to merit him being shut down in the view of some students.

As The Chronicle reported, shortly before his talk, an associate professor of English at Washington emailed a student a link to George’s accountability profile from the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation that carried several examples of George’s anti-LGBTQ remarks. The information spread on campus and the groundwork for the protest was set.

Certainly, many reasonable folks would be repulsed by comments attributed to him. Of transgenderism, he said in 2016, “There are few superstitious beliefs as absurd as the idea that a woman can be trapped in a man’s body and [vice versa].” When New Yorkers supported gay marriage in 2011, he hearkened back to a time when being gay was “beneath the dignity of human beings as free and rational creatures.” He had cofounded the National Organization for Marriage. And he argued that gay relationships have “no intelligible basis in them for the norms of monogamy, exclusivity, and the pledge of permanence.”

Moreover, it appears from a January 2023 piece in the Princeton Alumni Weekly that George hasn’t updated his views any. In that piece, titled “Crashing the Conservative Party,” he bemoaned the arrival at the university in recent years of students who “are just, you know, fully in line with — totally on board with — can give you chapter and verse as if it’s the catechism of — the whole ‘woke’ program: environmentalism, racial issues, sexual issues, and so forth.”

Of course, the students at Washington didn’t give him the chance to make his case against “illiberalism.” Nor did they challenge him to defend his views on sexual identity or abortion. They just made enough noise to drive him out.

FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, complained about the “heckler’s veto” imposed on George, suggesting that college security officials should have escorted the protesters out of the room. The outfit said they were entitled to hold signs in the back the room or make “fleeting commentary,” so long as they weren’t disruptive.

“But when the event cannot proceed as planned because protesters talk over speakers, drown them out with other sounds, or cause other disruptions that substantially impede the ability to deliver remarks, Washington College must use the resources at its disposal to prevent this pernicious form of mob censorship, and to ensure audiences can, at the very least, hear the speakers talk,” FIRE Program Officer Graham Piro wrote. “When Washington College allows silencing of speakers like George, its message to all in the campus community is that those who engage in disruptive conduct have the power to dictate which voices and views may be heard on campus.”

One could argue that, despite his achievements and honors, George is simply an intellectual dinosaur whose views on sexual matters don’t even warrant conversation. Notwithstanding their roots in his apparently deep religious faith, those attitudes are simply well past their expiration dates. After all, same-sex marriage was legalized nationwide in 2015 and long before that was declared legal in many states.

But we would then face a conundrum. In fact, those views – however benighted they seem to many – are still shared by a fair number of Americans. A year ago, the Pew Research Center reported that 37% of those surveyed thought same-sex marriage to be bad for society, for instance. And abortion continues to polarize the public.

So, does shutting down a talk by someone who espouses such attitudes make the views disappear? Would it not be more sensible, instead, to hold those stances up to scrutiny? Would it not be better for protesters even to shun his appearance and, perhaps, set up a presentation by someone who could refute the ideas? Or, even better, to put someone such as George on a stage with an intellectual opponent to argue their different cases?

After all, isn’t one of the purposes of higher education to hash out difficult matters and to teach students to think about them critically? Wouldn’t such a session serve everyone better than just making noise?