Business reporter John Rebchook’s face is worth studying. It may be the face of the new journalism – or at least one of them.

Business reporter John Rebchook’s face is worth studying. It may be the face of the new journalism – or at least one of them.

Let’s get to know him a bit. Some 30 years ago, John cut his teeth in journalism at the El Paso Herald-Post. While there he wrote a lede that proved memorable enough to be included in Mel Mencher’s Reporting and Writing textbook, one a lot of us grew up on. The lede went like this:

In less than three miles, Joseph L. Jody III ran six stop signs, changed lanes improperly four times, ran one red light, and drove 60 mph in a 30 mph zone all without a driver’s license. Two days later, he again drove without a driver’s license.

This time he ran a stop sign and drove 80 mph in a 45 mph zone. For his 16 moving violations Jody was fined $1,795.

He never paid. Police say that Jody has moved to Houston. Of the estimated 30,000 to 40,000 outstanding traffic warrants in police files, Jody owes the largest single amount.

Still, Jody’s fines account for a small part of at least $500,000 owed to the city in unpaid traffic warrants.

In February, Mayor Jonathan Rogers began a crackdown on scofflaws in order to retrieve some $838,000 in unpaid war¬rants. As of mid March, some $368,465 had been paid.

Clever, eh? It’s a classic example of the delayed lede, one that teases the reader a bit before getting to the point, or nut graf, of the story. Today, however, I suspect that such a lede would suffer a swift death in an editor’s keyboard. Even John, in his new life as a Web journalist, would likely spike it as ill-suited to our impatient, get-to-the-point times.

Nowadays, John’s prose goes more like this:

Colorado Attorney General John Suthers announced today that his office has filed a lawsuit against Western Sky Financial, a South Dakota-based online lender, and its principal, Martin A. Webb, for making unlicensed, high-interest loans to Colorado consumers.

According to the lawsuit, filed in Denver District Court, the company made more than 200 loans to Colorado consumers since at least March 2010, during which time it was not licensed with the state. The loans to ranged in value from $400 to $2,600 and had terms ranging from seven months to 36 months. The loans’ annual percentage rates ranged from 140 percent to 300 percent.

John’s reporting today can’t dally or tease. He gets to the point in part because he’s not writing for a newspaper any longer, but rather for his own blog, the pleasantly green-logoed Inside Real Estate News: Colorado’s Real Estate News Source.

John’s readers, like Net readers generally, have little patience for cleverness or meandering. They want the news at the top, so they can move on quickly if it doesn’t grab them. They don’t graze languidly, but rather rush to pull out the news that is relevant to their business. They take what they need and dash off to the next meeting.

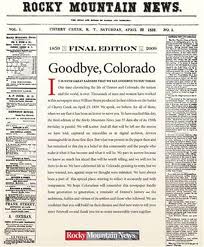

John, who worked at the Rocky Mountain News for some 26 years until it folded in 2009, is an example of a new kind of journalist. It’s not just his prose that makes him interesting. It’s his business.

When the Rocky died, John took his expertise as the paper’s longtime real estate editor and created his Net product. It’s a vehicle for and about players and projects in the real estate industry in Colorado. He has a few sponsors who pay for ads on his site and, he says, help him make a living (albeit not quite as cushy a living as when he was a veteran editor at the Rocky.)

When the Rocky died, John took his expertise as the paper’s longtime real estate editor and created his Net product. It’s a vehicle for and about players and projects in the real estate industry in Colorado. He has a few sponsors who pay for ads on his site and, he says, help him make a living (albeit not quite as cushy a living as when he was a veteran editor at the Rocky.)

As Inside Real Estate News grows, however, John expects that the returns will grow, too. He’s so confident in it that he recently turned down a job at a local weekly in Denver. He likes being his own boss, he says.

Lots of journalists may wind up running their own shows in coming years. Online reading is surging as traditional print newspapers struggle. And the fate of outfits such as The Huffington Post, recently sold to AOL for $315 million, suggest that the appetite for well-devised Web products is hefty. (John, would you settle for 1/315th of that?)

Of course, would-be Web journalists do have to bear a few things in mind, and John’s experience underscores them. First, he offers content that is in high demand, at least in certain circles. Much of what he does is specialized and it isn’t commodity news readily available in lots of other places. What’s more, he works fast, getting his news out ahead of the pack.

Finally, John is able to handle the business side of his operation, taking time to market his services to advertisers even as he stays on top of the news. He stays on top of the growth of the Net, too, putting out the word about his blog on Facebook.

John’s grinning punim isn’t the only look of journalism in the future. TV, magazines, and other vehicles will likely have a place, alongside some newspapers – on the Web or not. But take a close look at him anyway. Whether in textbooks or on the Net, he has plenty to teach us.