Almost no country can do big things as well as China can. It rebuilt a sprawling section of Beijing to make room for the Olympics a few years ago. It has created a subway system in the city that has few peers. Its bullet trains have narrowed vast distances between cities whose stunning architecture is almost certainly the most advanced on the globe. It is building a vast system for moving water from the lush south to the dry north, a nation-spanning effort that residents of the U.S. Southwest could only marvel at.

So why can’t Beijing do something about pollution? We’re not talking about a little whiff of smoke every now and then. No, the city’s air is so bad that popular wisdom here says the numerical scale for measuring it had to be expanded. On many days, the poisons are so bad that the U.S. Embassy warns people to stay indoors with windows closed. The embassy provides a Twitter feed to measure air quality hourly, and was embarrassed a while ago when the term “crazy bad” went out on the feed by mistake. The air that day was 20 times as bad as the guideline provided by the World Health Organization.

People here buy household air purifiers and sophisticated masks. Without protection, one hardly wants to go out – you can feel the weight of the bad air deep in your lungs. Teary eyes, runny noses and scratchy throats are the norm. Wholly enervating.

What’s more, the pollution sullies the air far from downtown. One can drive an hour and an half north, going into the mountains, and still not escape the eye-stinging smog. Early afternoons look like dusk on bad days, with no hint of a sun up beyond the foul, dense mist. Friends compare it to a sci-fi movie set in a world where ecological disaster blotted out the light. It’s common to see people wearing surgical masks – some fancy, colored types — on the roads of the city.

Troublingly, it’s not as if China can’t cut down on the smog. For big events, such as the Olympics — and, probably, the recent Beijing Marathon — authorities can shut down the factories and power plants. Routinely, they limit driving by alternating odd and even license plates to try to contain road-choking traffic and, incidentally perhaps, limit foul emissions. Officials supposedly seed the clouds in normally dry Beijing at times to clear the air. And certainly there are clear, nice days, when the sky is blue and the sun brilliant — just too few of them.

Indeed, it’s ironic that China sees the growth of green energy around the world as a great business opportunity. It plans to be a global powerhouse in the production of devices and technology to serve the needs of the world’s businesses for ecologically sound production techniques.

And yet, China continues to depend for much of its energy on coal. Wagons haul the stuff around for people to buy for cooking. Much of the country’s electricity comes from coal, and one doubts that this is the so-called clean coal of the West. Certainly, if coal accounts for much of Beijing’s visibly awful smog, it is anything but clean. Fossil fuels, in general, drive this economy, just as they do that of the U.S., windmills aside.

China’s leaders are smart people. As they permit the pollution to ravage their people – creating God knows what amount of disease now and in the future – they must have made some sort of cost-benefit calculation. They must have weighed the costs of their headlong rush to modernize against the environmental harm their policies are causing, and judged that public health (and comfort) can be sacrificed. As they’ve let millions of cars take the place of millions of bicycles in just the last decade or so, they must have calculated that their people feel the tradeoff is worth it – wealth for health.

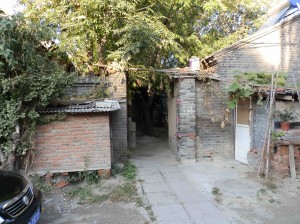

Then again, one has to wonder whether it’s been all that conscious and deliberate. The astounding growth of the last couple decades has brought many discomforts – inflation, widening inequality in income, the destruction of ground-level life in neighborhoods formed by low-profile warrens known as hutongs in favor of endless rows of high-rise apartment blocks. Much of the change has been good, of course, and the use of market forces to accomplish it is testimony to how powerful such forces can be. And it may be that pollution – certainly an unintended consequence – has come along as just another unpleasant byproduct. Controlling it may now just seem too difficult, with too many people committed to keep the steamroller growth going at any cost.

A friend from Japan says Chinese leaders are trying to address the issue. They have been in consultation with Japanese scientists and experts who wrestled down much of their pollution problem years ago. They’d like to rein in the problem here in China and do so even as they keep growing their economy.

But one wonders how far off the solution will be. Sadly, I’m reminded of the Lyndon LaRouche folks back in the U.S. They used to argue that the drive to control pollution, especially efforts to halt it in the Third World, was part of some bizarre conspiracy to keep poor countries poor. That was nonsense, of course. And certainly there’s no conspiracy now within developing countries to foster pollution. Still, tolerating the poisonous air is a choice. And for many of today’s Chinese – young and old – that choice will prove to be a deadly one.