Isn’t there an ancient myth about an oracle that reflects different images of the same event to different viewers? Celebrations of Christmas seem like that to me, especially after watching the buildup to the holiday in China.

Isn’t there an ancient myth about an oracle that reflects different images of the same event to different viewers? Celebrations of Christmas seem like that to me, especially after watching the buildup to the holiday in China.

China, of course, has little history to make Dec. 25 any more than just another day. For modern China, where atheism is a requirement for Communist Party membership, celebrating Christmas is odd, to say the least. Mao would spin wildly in his grave at the idea. And Buddhists, who practice the dominant religion in the country, would have little use for marking a foreign god’s birthday. And yet, the Chinese have rushed to embrace the day – though in their own peculiarly non-religious way. They see in it what they want to see, just as many Americans do.

Celebrations of the day abound in China, at least in the cities. It’s a big day for young people, especially, who wish one another Merry Christmas. Some, particularly lovers, give each other presents. One of my teacher’s aides at Tsinghua, a bright young man going through the grueling yearlong process of applying for membership in the Party, was fretting over what to get his girlfriend, for instance. (Let’s not tell his Party sponsor about that). And Wei Wei, a delightful grad student, just sent me an electronic Christmas card on the Tencent system, a Chinese email system.

It’s a bit of a mystery, this adoption of the holiday. Certainly, it’s understandable why the department stores in Beijing would deck themselves out for the day. Like American retailers, they’ve found that carols on the PA systems, twinkling lights and images of Santa, reindeer and decorated evergreens help drive people to buy. It’s a retail holiday in the States, too, of course. There’s a buck (or a yuan) to be made. Plus, in Beijing, there are Westerners to cater to.

It’s a bit of a mystery, this adoption of the holiday. Certainly, it’s understandable why the department stores in Beijing would deck themselves out for the day. Like American retailers, they’ve found that carols on the PA systems, twinkling lights and images of Santa, reindeer and decorated evergreens help drive people to buy. It’s a retail holiday in the States, too, of course. There’s a buck (or a yuan) to be made. Plus, in Beijing, there are Westerners to cater to.

But there’s more to it in China. The Chinese seem to see Christmas as part of what it means to be like the West. They have a manic drive under way to teach English to all school kids. They have taken to capitalism in ways that would stun Adam Smith and are worrying demagogic American politicians. Some 120,000 Chinese are studying at American universities, including my own school, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, where we are forging exchange alliances with Chinese schools.

China is going through a headlong love affair with all things foreign, a feeling of being smitten that is almost adolescent in its passion. A saying in the country holds that the moon shines brighter on foreign lands, and the American moon in particular has the Chinese in full swoon. Indeed, Beijing, Shanghai, and even inland cities such as Xi’an, along with British-dominated Hong Kong warm to anything American. Just look at the proliferation of outlets for Starbucks, McDonald’s, KFC and Pizza Hut, not to mention American-branded clothes and other products (even counterfeit ones). Steve Jobs was mourned in ways no Politburo member could expect to be (counterfeit copies of the new biography graced peddler’s carts seemingly in minutes after it was issued; I got one for the equivalent of $3).

China is going through a headlong love affair with all things foreign, a feeling of being smitten that is almost adolescent in its passion. A saying in the country holds that the moon shines brighter on foreign lands, and the American moon in particular has the Chinese in full swoon. Indeed, Beijing, Shanghai, and even inland cities such as Xi’an, along with British-dominated Hong Kong warm to anything American. Just look at the proliferation of outlets for Starbucks, McDonald’s, KFC and Pizza Hut, not to mention American-branded clothes and other products (even counterfeit ones). Steve Jobs was mourned in ways no Politburo member could expect to be (counterfeit copies of the new biography graced peddler’s carts seemingly in minutes after it was issued; I got one for the equivalent of $3).

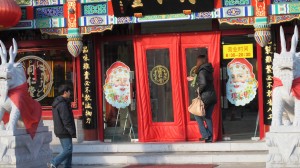

The odd thing, of course, is that it’s Christmas without Christ. The imagery gracing the stores – which, you can be sure, is Party-approved or at least not opposed – is all about Santa Claus, trees and reindeer. One does not see crucifixes, crèches or pictures of Jesus (not that there are many of these in American malls either). A friend says her nine-year-old daughter has been practicing to sing in a school Christmas pageant, though there won’t be any religious elements in it (I’m not sure how many non-religious songs there are beyond Jingle Bells and Frosty the Snowman. But, even if Silent Night is on the list, the religious words would be sung without any divine intent).

Many of my non-religious friends in the U.S. take the same tack, of course. Even some Jews have Christmas trees (“Hanukkah Bushes”), arguing that such pagan-derived symbols are part of the non-religious character the holiday has taken on. It’s just a cultural thing, they say, and what’s wrong with giving presents and offering one another good wishes? Then, of course, there’s the idea that no occasion for a party ought to be passed up.

Many of my non-religious friends in the U.S. take the same tack, of course. Even some Jews have Christmas trees (“Hanukkah Bushes”), arguing that such pagan-derived symbols are part of the non-religious character the holiday has taken on. It’s just a cultural thing, they say, and what’s wrong with giving presents and offering one another good wishes? Then, of course, there’s the idea that no occasion for a party ought to be passed up.

Still, there’s something shallow about the Chinese celebration of the holiday. It has a hollow ring. Along with stripping out the religious elements, the Chinese have no traditional basis for the day, nothing that links it to anything Chinese. Far more important, of course, are the Chinese New Year and other holidays where it seems the whole nation is on trains and planes to get home. Those days, far older than anything we have in the West, are all about the warmth of family.

For now, Christmas in China still is no home-and-hearth holiday. People work on the day. Schools remain in session, at least when the date falls on a weekday. And present-giving hasn’t become the potentially bankrupting affair that it is for so many American parents. Oddly, perhaps, that’s heartening. Sure, it’s funny to see pictures of smiling, white-bearded, red-nosed St. Nick (of course, one wonders if the Coca-Cola-fostered image has anything to do with the saint). But, Scrooge-like as it may sound, there’s something pathetic about it. China has plenty of traditions to mark, after all, and many have been around longer than the couple thousand thousand years Westerners have been marking the mid-winter holiday.