A cruise offers a few lessons

Some 52 years ago, I made a silly mistake. Seeing myself as very much a counterculture creature at that time, I looked on high school proms as just so unhip. The formal clothes, corsages, etc., were just not my jam, as we might say now. They seemed so, well, Establishment and the cool kids were anything but that. So, I skipped my prom.

Now, I have a different view. Such anti-Establishment notions, it seems to me today, were essentially snobbish, ways of looking down one’s nose at others who were just not “aware” enough (today we might say “woke”). I didn’t disdain friends who rushed off to rent formal clothes, and get dates, photographs and limos arranged, but I thought the scene just wasn’t for me. Somehow, I was above or at least apart from all that.

Of course, I would have liked the motel rooms that groups of the guys booked at the Jersey Shore for them and their well-coiffed newly adult (i.e., about 18 years old) girlfriends. But that would have been for other reasons.

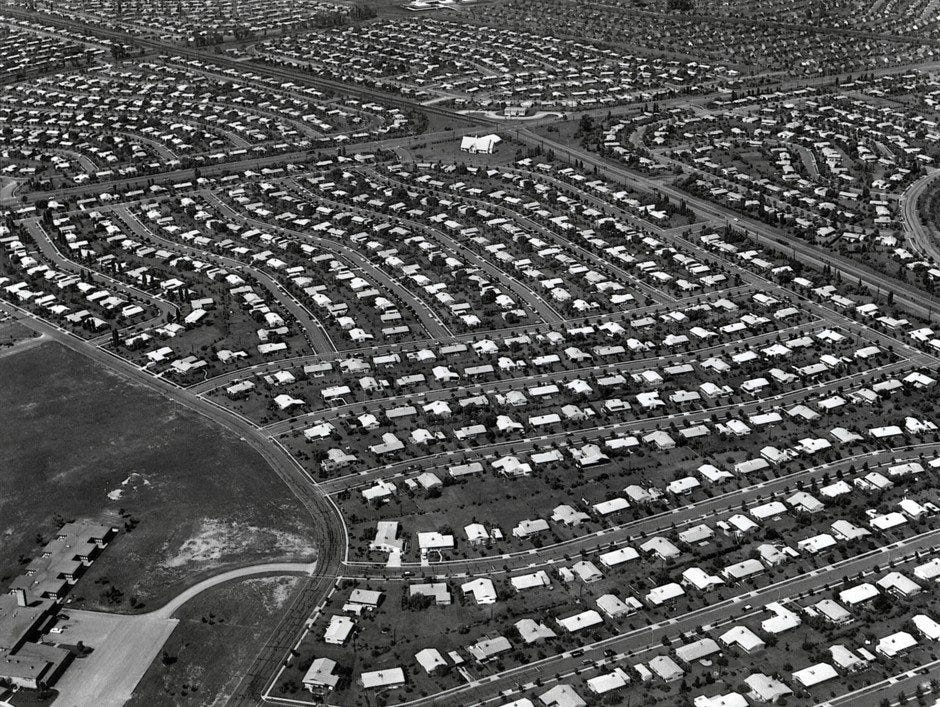

I’m put in mind of all this because I just got back from what surely has to be one of the most Establishment things one can do — a cruise on the Disney Dream. For a week, my wife and I, our son and daughter-in-law and three grandkids steamed about the Mediterranean. We stopped off at a few Greek islands and we spent a good bit of time on board a very large ship, one that holds 4,000 souls and a host of cartoon characters.

This was, in some ways, very prom-like. Girls and women on such trips dress up as princesses, men and boys as pirates or princes – and those are not just the employees, but the cruisers. Meanwhile, Disney employees parade about, decked out as Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck and a host of others in the Mouse House universe, strutting and posing for photos to the delight of kids and their parents, alike.

All the while, music from uplifting Disney movies plays in the background on nearly all 13 decks on that ship. Some tunes are reprised during evening shows when cast members in Broadway-style productions caper about on a stage suited to any New York legitimate theater. Think “Beauty and the Beast” in a venue that rocks and sways slightly. The production values are impressive.

And then there’s the food. It’s unlimited at breakfast and lunch and is exceptionally varied. In the evenings, dinner rotates among several lavishly appointed restaurants. We skipped the adults only restaurants, though they were there for those wanting to get away from the kids for a while. For such times — or anytime — there were, nursery and kid’s club programs (that kids, like the 3-year-old with us, really, really want to go to).

A couple wading pools and an adults only pool (complete with wade-up bar) round out the offerings. And above it all, folks can fly through a tube on fast-rushing water, the AquaDuck water coaster. Remarkable fun. There’s also a track for burning off the many calories one consumes, along with a workout room and spa.

I’m no Disney cultist of the sort found at times in the parks and on the ships – people who count their visits on many more than two Mickey hands. But our weeklong adventure, to and from a port near Rome with stops in Naples/Pompeii, Mykonos, Santorini, and Chania on Crete, was extraordinary. Yes, it was the ultimate conventional tourist thing to do, but it was wonderful.

Reality, of course, is all too ugly at times in ways that make Cruella De Vil and evil stepmothers seem far too tame. But with Disney one can be immersed in a fantasy world that can be surprisingly engaging when seen through the eyes of the 6-and-under set, like our grandkids. Piracy in the real world is monstrous, but on the boat it’s all makeup and “aarghing.”

Moreover, the real-life elements that make Disney ride high among entertainment and hospitality companies are exceptional. From a business point of view, the company knows its markets, knows what its public wants, and it serves that up to a fare-thee-well.

On board the Disney Dream, the details knock your socks off (or those yellow Mickey shoes, perhaps). Portraits of characters around the ship move and talk when one stands before them. Waiters know what the kids eat each night. The level of cleanliness in the halls and staterooms (post-cleaning) is the definition of shipshape.

And the staff — the “cast members” — bring their A-game each day. From stateroom “hosts” who make the beds to ship mechanics, people greet guests warmly on sight. Each night, the ship’s officer group –- clad in Navy-like dress whites – gather for events to chat amiably with guests.

As I dealt with the multilingual and ethnically varied crew and staff, as well as with fellow guests, I was reminded of a bright, bold contrast, one involving the blinkered view of the world that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis brought to his silly fight with Disney. Recall that DeSantis in 2022 signed the Parental Rights in Education Act. As NPR reported, the “Don’t Say Gay” law restricts how sexual orientation and gender identity are discussed in the schools. Disney’s former CEO Bob Chapek spoke out against the law and said he’d work to overturn it. “That angered DeSantis, who then worked with Republican lawmakers to pass a measure revoking Disney’s self-governing status,” NPR said.

DeSantis, of course, also derided the “wokeism” that he argued plagued Disney. The company famously reaches out to customers and staff of varied backgrounds and orientations, and the governor lambasted that approach as he tried to appeal to a very different constituency – the straight, white anti-LGBTQ and anti-immigrant crew that dominates the MAGA GOP.

On the ship, the variety of people that Disney serves and employs is apparent. The cruises draw passengers of all sorts, including straight white folks. Its crew includes people from all across the world, some of whom (such as our dinner servers) are supporting families back in India and elsewhere with their earnings from several-month stints on board ship.

Disney both employs and serves the broadest of markets. Its “wokeism” and its aggressive embrace of diversity may have offended DeSantis (or perhaps he was just being opportunistic about that). But the company’s decisions to appeal to a rainbow-like array of constituencies in films, music and other vehicles (including ships) are simply smart business moves. Disney CEO Bob Iger, who succeeded Chapek, may or may not share a welcoming ideology, but he knows what his customers and staffers want. He knows those whom he serves.

DeSantis’s political moves, by contrast, seemed aimed at a very narrow slice of the electorate, one that surely will diminish in time. MAGA bigotry and narrow-mindedness won’t disappear, of course, but demographics suggest it will appeal to fewer and fewer Americans over time.

So Disney is remarkably conservative – consider those carefully coiffed princesses and happy tales of good prevailing over evil – but also progressive. It is prom-like but with a modern spin, perhaps something akin to the group dates that many high schoolers now indulge in, rather than conventional couples nights out.

Curiously, today’s wokeism is really just an updated version of the counterculturalism of my high school years in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In that sense, a Disney cruise or visits to the parks can be pretty hip things to do.

I later regretted missing my prom, but I’ve made up for it with visits to Disney parks in Florida and outside Paris with grandkids, along with that cruise. Smitten with the Dream, my wife and I are making arrangements for another such big boat ride next year, this one with more grandkids.

I still can’t quite bring myself to wear those Disney ears, as some adults on the cruise did. But, if one of the grandkids insists, I won’t fight too hard.