There are better remedies for antisemitism

As longtime bastions of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, several Ivy League schools were once terrified of opening their doors to Jews. A. Lawrence Lowell, Harvard’s president from 1909 to 1933, contended that “where Jews become numerous, they drive off other people and then leave themselves.” He dismantled the university’s Semitics department and tried to introduce a quota for Jews, alarmed that the share of Jewish students grew from 6% to 22% between 1908 and 1922.

At Yale, a 1922 memo from an admissions chairman urged limits on “the alien and unwashed element,” a phrase from a document found in a university folder labeled “Jewish Problem.” Reflecting a general distaste for diversity, Yale medical school Dean Milton Winternitz in the mid-1930s said: “Never admit more than five Jews, take only two Italian Catholics, and take no blacks at all.” As it turned out, Yale in 1923 adopted an informal quota limiting Jews to no more than 10% of the undergraduate student body, a figure that held sway until the early 1960s.

Worried about the large share of Jews enrolled at Columbia, the school went so far in 1928 as to set up a separate preprofessional college in Brooklyn, Seth Low Junior College, where many Jewish students were routed. As the Columbia Spectator reported, SLJC was created expressly to reduce the number of Jewish students on the main Morningside campus. In “Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University,” Columbia historian Robert McCaughey notes that enrollment of Jewish students at Columbia College after the junior college opened dropped from 40% to 25%.

The two-year junior college was shuttered in 1936, but not before editors on the school paper, “The Scop,” derided Jews as displaying “sneering, hypercritical, protesting, and disloyal characteristics.” The editors added that “only a small limited number of Jews can be assimilated each year. They [the universities] often cite incidents, from past experiences, of disloyalty, redundant individualism, and undeserved disparagement which they claim have been characteristically displayed by large bodies of Jewish students.”

As reported by The Current, the editorial board at the paper was almost entirely Jewish, a discomfiting element that Jews who camped with today’s antisemites might take note of. “The fact that a predominantly Jewish group of students wrote such a virulently anti-Semitic editorial proves how deeply ingrained these impressions of Jews were within society at the time, or at least within the academic elite,” The Current noted. “The Scop editorial board internalized the unfavorable rhetoric about Jews that surrounded them, and believed it was smart for Columbia College to limit its number of Jewish students, for if it didn’t do that, it would end up as miserable as Seth Low.”

At SLJC, one student was a young Isaac Asimov, who later wrote of a bad conversation with an admissions officer: “The interviewer didn’t say something that I eventually found to be the case, which was that the Seth Low student body was heavily Jewish, with a strong Italian minority. It was clear that the purpose of the school was to give bright youngsters of unacceptable social characteristics a Columbia education without too badly contaminating the elite young men of the College itself by their formal presence.“

Given that background, the debate over the best response to Jews coming under siege – sometimes physically — amid pro-Palestinian encampments at such schools is especially painful. After decades of Jews having to hammer on the doors to get into the nation’s top schools, it is troubling to read impassioned arguments that they should stop knocking and go elsewhere.

Attacking several elite schools for antisemitism and a host of other evils that he conflates, for instance, Mosaic Magazine publisher Eric Cohen writes in “The Exodus Project:” “These colleges are controlled by true believers. Their faculties and administrators enthusiastically embrace the very world view – call it ‘intersectionality,’ call it ‘critical race theory,’ call it ‘wokism,’ call it ‘DEI,’ call it ‘social justice,’ call it whatever you want – that nurtured the civilizational assault that now treats the Jews and Israel as target number one and America itself as the big game.”

Cohen’s answer: Jews should abandon such Northeastern schools and instead head to Texas, Florida, Alabama and such. “We simply need to celebrate and encourage the new exodus; and we need to help make the best of these schools into true exemplars of academic excellence. ‘Wow Harvard!’ should give way to ‘Why Harvard?’”

Earlier, in a City Journal piece headlined “Columbia is Beyond Reform,” Tablet editor at large Liel Leibovitz similarly argued: “The administrators seem beyond redemption. Sad to say, but the students are, too: very few at Columbia, veterans of seminars about allyship and intersectionality, bothered stepping out and standing together with their beleaguered Jewish peers.”

Leibovitz, an Israeli who earned his doctorate at Columbia, concluded: “Maybe it’s time to let Columbia, Yale, and other elite schools become what they already basically are: finishing schools for the children of Chinese, Qatari, and other global elites. And let anyone interested in America’s future pursue education elsewhere. For some, this will mean applying to alternative institutions, like the University of Austin; for others, trade schools might offer a remunerative alternative.”

But is shunning such schools really the best course for Jews, for the schools, for American society? Would it not be better if, instead, more Jews attended them and if Jewish donors stepped up to fund programs aimed at educating all the students on such campuses about antisemitism and Jewish history (particularly in Israel)? Would it not be better if curricula such as Columbia’s famous core curriculum were modified to include such mandatory instruction?

Indeed, amid a national rise in antisemitism, is fleeing to schools in Florida, Texas and elsewhere even reasonable? Dara Horn, a Harvard graduate and author of the nonfiction essay collection “People Love Dead Jews,” writes of her travels around the country in which she met many Jewish college and high school students who accepted the casual denigration of Jews as normal. “They are growing up with it,” she writes in a piece for The Atlantic. “In a Dallas suburb, teenagers told me, shrugging, about how their friends’ Jewish fraternities at Texas colleges have been ‘chalked.’ I had to ask what ‘chalking’ meant: anti-Semitic graffiti made by vandals who lacked spray paint.”

Horn served on a now-disbanded antisemitism committee created at Harvard by ousted president Claudine Gay, but has become a critic of the university’s efforts to combat antisemitism. She is also a member of a group of Jewish alumni examining Harvard’s courses for antisemitism, according to The Boston Globe. As reported by the Globe, she told the group that “there are entire Harvard courses and programs and events that are premised on antisemitic lies.” Horn cited the spring 2024 course Global Health and Population 264: ‘The Settler Colonial Determinants of Health’ as an example of one such class in her article for The Atlantic.

Would it not be better if alumni and others likewise scoured courses at Columbia, Yale and other schools – including many not in the Ivy League – in efforts to eliminate antisemitism? Would many courses in Middle East Studies departments survive such scrutiny? Should they? Already, Columbia has taken steps to review or oust academics who’ve violated school policies with antisemitic comments – see the cases of Mohamed Abdou, Hamid Dabashi and Joseph Andoni Massad – and should more such efforts not be encouraged? Would such departments do better for students and the research world with a faculty that is not overwhelmingly Arabist, but more balanced?

And would it not be better if, instead of abandoning appropriate efforts at education in diversity, equity and inclusion — a bête noire of the right — that DEI training be broadened to include Jews as a vulnerable group? Have the repeated instances of antisemitic violence not demonstrated such vulnerability enough?

To be sure, this would take some doing, as Horn implies:

“Many public and private institutions have invested enormously in recent years in attempts to defang bigotry; ours is an era in which even sneaker companies feel obliged to publicly denounce hate,” Horn writes. “But diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives have proved to be no match for anti-Semitism, for a clear reason: the durable idea of anti-Semitism as justice. DEI efforts are designed to combat the effects of social prejudice by insisting on equity: Some people in our society have too much power and too much privilege, and are overrepresented, so justice requires leveling the playing field.”

As she argues, antisemitism is a different sort of animal and one, I submit, that demands a different approach in DEI programming.

“It is a conspiracy theory: the big lie that Jews are supervillains manipulating others,” Horn writes. “The righteous fight for justice therefore does not require protecting Jews as a vulnerable minority. Instead, it requires taking Jews down. This idea is tacitly endorsed by Jews’ bizarre exclusion from discussion in many DEI trainings and even policies, despite their high ranking in American hate-crime statistics. The premise, for instance, that Jews don’t experience bigotry because they are ‘white,’ itself a fraught idea, would suggest that white LGBTQ people don’t experience bigotry either—a premise that no DEI policy would endorse (not to mention the fact that many Jews are not white).”

Apparently unlike the critics of DEI, I should note that I learned a lot from DEI programming at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Talking with Black colleagues about issues generally never aired was helpful; in fact, few white faculty members are aware of everyday slights that some Black colleagues face — one told me he routinely was questioned by police when he approached a university building in casual clothes on a weekend, something his white peers didn’t run into. I also read several helpful books that I otherwise would not have picked up.

And I learned a great deal co-teaching a course in which students examined past news coverage in Nebraska of racial and ethnic matters; it was a remarkable experience for me and my students alike. That course came about because issues of racial discrimination in the state were much on the mind of some administrators and faculty and a past Omaha World-Herald editor in the wake of the George Floyd killing.

As should be evident from my questions, I find the arguments for abandoning the Ivy League schools and others unpersuasive, even harmful. In part, this is because I have had warm ties to such schools – much of my professional and academic success came from my attending the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, a place that was eye-opening for me (in part because of a brilliant Jewish faculty member). Also, one of my daughters graduated from Columbia College and the other, who is now a rabbi, from the Jewish Theological Seminary, which associated with Columbia.

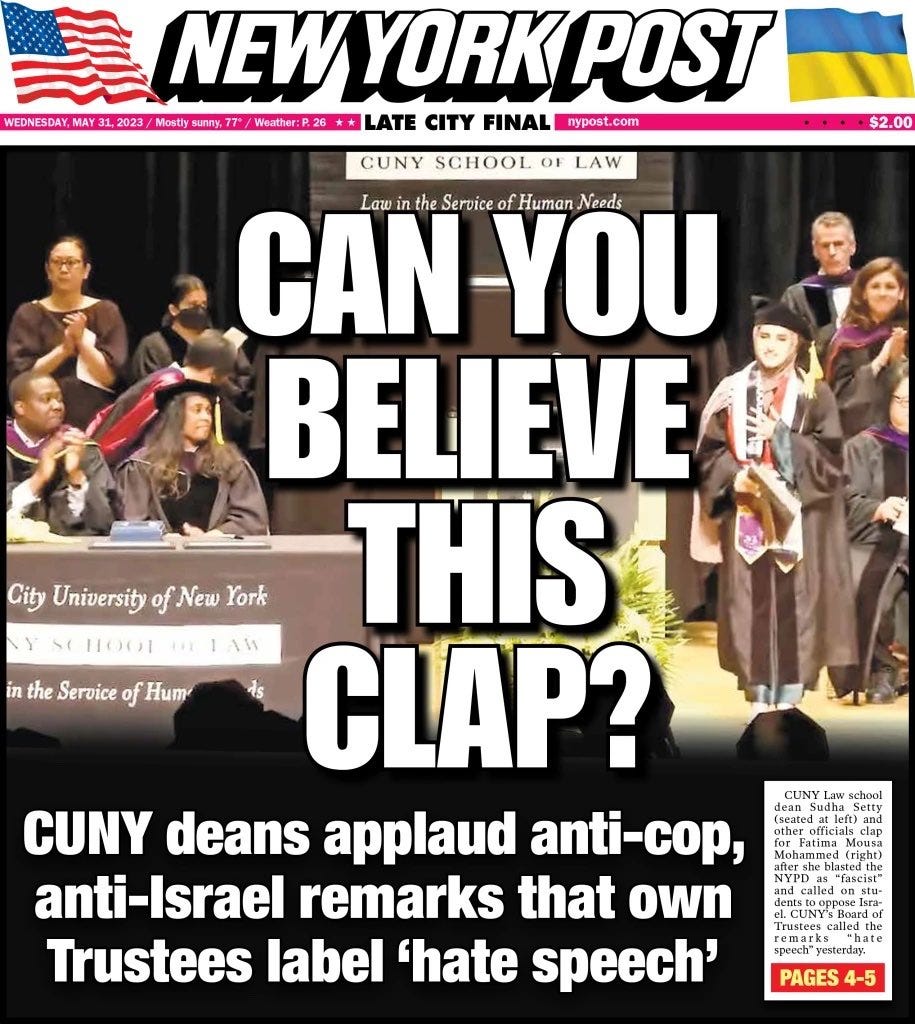

But I am not blind to the flaws at Columbia and elsewhere. They’ve been dramatically underscored by the encampments, which to me are evidence of poor education about Israel, Palestine and the Middle East. Personally, in fact, I felt the sting of some of the bigoted attitudes among faculty members; my book about Islamist terror, “Divided Loyalties,” was accepted a few years ago for publication by the Columbia University Press, only to be blackballed by a lone faculty member on the press’s advisory committee because the person objected to the university publishing anything on Islamist terror. (The Michigan State University Press, fortunately, did not share those objections).

Nonetheless, I believe the answer to the gaping flaws at such schools is not to boycott them, a response oddly reminiscent of the boycott Israel efforts so common among some academics now. Rather, the answer is to fix the schools, to implement curricula that would combat the ignorance that fuels the encampments and drives antisemitism. I believe the answer includes endowing positions for academics who can teach from the viewpoint of fostering coexistence between Israelis and Arabs in and around Israel.

In sum, I believe the answer is to engage with such schools, not to desert them. They are too important to leave to the antisemites.