The Messenger lost millions and now a lot of journalists have lost work

With the sudden death of The Messenger, an ambitious news site plagued by trouble from without and within, mass media has suffered another devastating blow. The outlet’s demise comes atop staff cuts at Time magazine, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times and Business Insider, layoffs that have cast hundreds of top-notch journalists onto unemployment lines.

There is plenty of reason to mourn this loss – not so much for the site, but rather for the people involved. As my former BusinessWeek colleague Tom Lowry wrote on LinkedIn, the shutdown made for “a tough day – brutal, really,” adding how “sad for all [his] The Messenger colleagues who find themselves suddenly without a job …” That group included some 300 people, half of whom were journalists, including many from A-list publications.

Along with Lowry, BW veterans working there included Ciro Scotti, Dawn Kopecki and Justin Bachman. These superb talents joined a similarly impressive group in the much-touted venture, which went live only last May. In that short time, the group on the site’s business news team did outstanding work, as Kopecki described in a sad LI post. Indeed, she was prepping the best efforts for journalism contests as the site’s owners shut it down.

But this latest collapse – along with the drip-by-drip bloodletting at other big pubs – raises the question of what kind of journalism we will have going forward. The Messenger was slammed by many critics for its lack of innovation, its attempts to duplicate the glories of a media environment long since gone. Even as storied outlets such as The New York Times still find a large audience, the journalistic innovators that are succeeding nowadays seem to be far more locally focused and to not rely on advertising of the sort The Messenger never quite got.

In short, most of today’s promising news operations reflect the decline of the mass approach and the rise of targeted efforts.

Take, for instance, a couple pioneering outlets from Nebraska, the Flatwater Free Press and the Nebraska Examiner. The Flatwater Free Press, supported by donors and subscribers, has broken some of the most important stories in its well-defined turf, including award-winning coverage of Nebraska’s prison and parole board. The Nebraska Examiner, a nonprofit that is part of the States Newsroom national network, broke news that cost a leading gubernatorial candidate his race.

In a neighboring state, The Colorado Sun, another subscriber-supported site, has won a slew of awards for its important journalistic work. The controversial introduction of wolves in the state, for instance, has made for a series of major pieces. Similarly, its tick-tock account of a devastating fire shed light on the vulnerability of residential areas to climate change.

Such local news operations – often manned by small staffs and backed by foundations, donors or subscribers – are doing what any business must; they are serving their markets. They offer local, tightly focused content that makes a difference in people’s lives, a bold contrast with the outsize – one might say inflated — ambitions of the founders of The Messenger.

Principal owner Jimmy Finkelstein, former owner of The Hill, had raised $50 million to launch The Messenger. He staffed bureaus in major cities with some of the best journalists from outlets such as POLITICO, the Los Angeles Times, NBC News and Reuters, wooing them with generous pay. As the Daily Beast reported, on The Messenger’s launch last spring, managers predicted that the company would bring in $100 million annually and average over 100 million hits a month by the end of this year. (In December, it drew 24 million visitors, the New York Times reported).

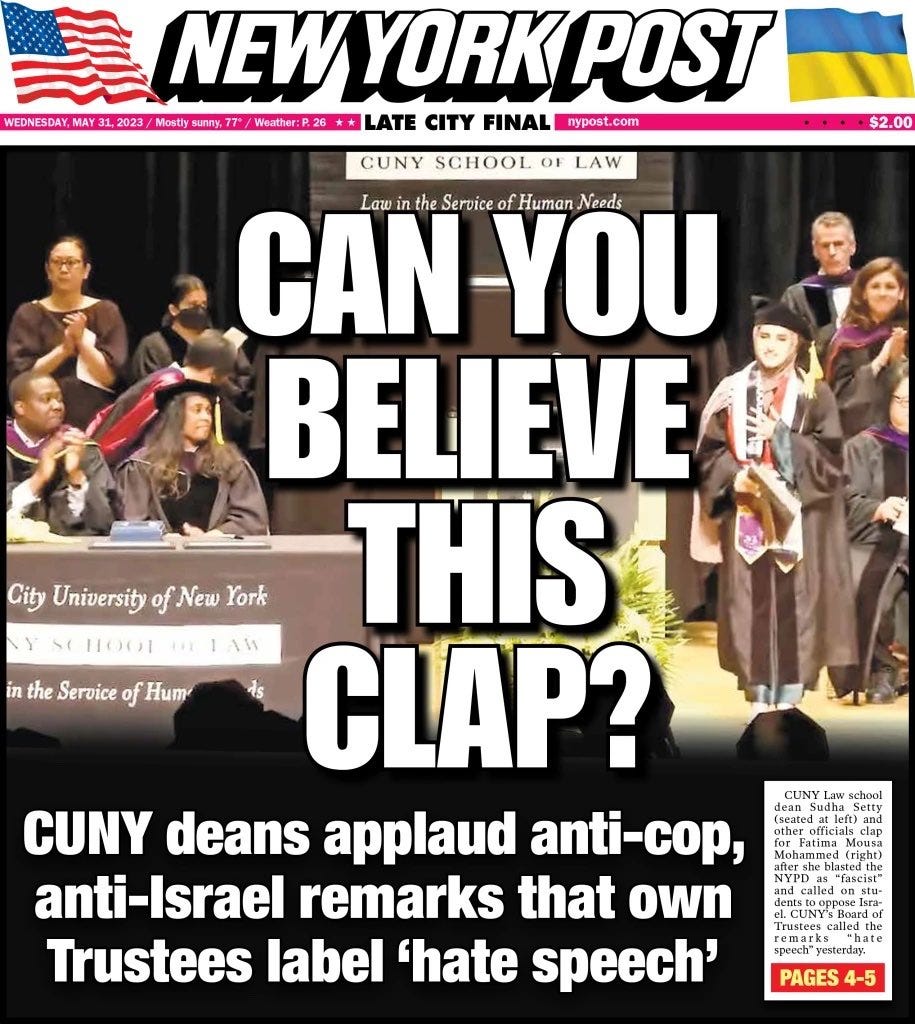

But the effort seemed doomed from the start. Months before its launch, critics derided its business plan as “delusional” and mocked its high-profile execs for trying to serve a media environment that no longer existed. Finkelstein, in his mid-70s, had said he hoped the site would appeal to audiences who had warmed to “60 Minutes” and “Vanity Fair.” As a critic quoted by the New York Post put it, “Whenever a new website references an old magazine and TV show, you know they are not looking towards tomorrow.”

Then, once it debuted, the site was troubled by internal friction, as well as criticism from outside. As The New York Times reported, staffers chafed at demands to rewrite competitor stories, as their editors pressed them to churn out work to build hits. Communication within the outfit was so poor that multiple teams of reporters worked on the same topics, unaware of each other’s efforts.

For me, much of this is reminiscent of the last days of BusinessWeek. Fifteen years ago, we were all scrambling to deal with the Net. And part of the answer was doing anything to generate traffic. We had a magazine staff and a separate online staff, but we all fed an online operation whose main metric, it seemed, was eyeballs. As Chicago bureau chief, I was routinely pressed to file anything and everything about Boeing, for instance, no matter how slight. Why? The big-name company drew traffic.

BusinessWeek ultimately was sold – for essentially nothing – to Bloomberg and rechristened as Bloomberg Businessweek. Just recently, Bloomberg announced that the weekly print edition will be taken monthly. Long before that, though — back in the 2007-09 period — there was a desperation about our efforts that seemed to be replicated so many years later at The Messenger.

Only days after The Messenger’s launch last May 15, politics editor Gregg Birnbaum quit, disgusted with the culture of the place. “Who doesn’t like traffic to their news site?” he said in an email shared by The New York Times. “But the rapacious and blind desperate chasing of traffic — by the nonstop gerbil wheel rewriting story after story that has first appeared in other media outlets in the hope that something, anything, will go viral — has been a shock to the system and a disappointment to many of the outstanding quality journalists at The Messenger who are trying to focus on meaningful original and distinctive reporting.”

With its biggest debut effort, an interview with former President (and Finkelstein friend) Donald J. Trump, the outlet bent over backwards to avoid seeming partisan, as it promised impartiality and objectivity. Instead, what it did was just to duck controversy, avoid hard issues. For giving Trump an uncritical platform, the admittedly partisan Mother Jones lambasted the Messenger as “just another media outlet that enables extreme politics and the inflaming of divisions.” MJ Washington bureau chief David Corn argued that when its “down-the-middle approach is applied to a political extremist, the result is not objective journalism but the amplification and legitimization of extremism—and that can threaten honest political discourse and even democracy itself.”

On the left, publications such as Mother Jones and, perhaps, The Atlantic, seem to have carved out niches. On the right, outfits such as National Review have found an audience, as The New York Sun and The Free Press are attempting to do. Outlets such as POLITICO endure by zeroing on specific interest areas, much as trade journals like The Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Ed serve particular markets. And, across the nation, the small nonprofits seem to fill a vital need in down-the-middle general interest news, albeit local (nothing like the grandiose targets The Messenger leaders aimed for).

It is surprising that the lessons of serving particular audiences were lost on Finkelstein. After all, he had been involved with such tightly focused publications as The Hollywood Reporter, Adweek, Billboard and The Hill, which his father, Jerry, co-founded in the 1990s with New York Times journalist Martin Tolchin. The younger Finkelstein raised some of the money for The Messenger by selling The Hill. But he had long lusted after bigger stages, in 2015 bidding unsuccessfully for New York’s Daily News.

In the end, The Messenger was the product of the flawed vision of a man who appeared to have little touch with an audience and less with the best interests of his staffers. As he burned through tens of millions, it appears Finkelstein didn’t bother to set aside anything for severance or health insurance for his staffers. Not surprisingly, some, have filed suit, seeking damages, as reported by Variety.

Finkelstein even slighted his staff in announcing the end of the publication. The staffers read about the shutdown first from reports in The New York Times, the Daily Beast and elsewhere before they got an email from the Florida-based failed mogul. For the journalists involved, this is a sad loss. Few, however, will shed a tear for the pied piper who led them down the rat hole.