Misinformation abounds in the Israel-Hamas war

As Israeli forces move in on the Al Shifa Hospital in Gaza, they and the world will soon learn whether their intelligence, corroborated by American information sources, is correct that the facility masks an elaborate underground Hamas command and control center. The denials by Hamas leaders about the site and their rejections of the charge that they use human shields – in this case, vulnerable patients – to protect their operations will either be validated or shown to be more disinformation.

But will the Arab world see or believe the reports? Or will it see what it chooses to see and is often fed, a nonstop parade of Palestinian victims in videos served up on CNN and other outlets? Will that world see mostly the propaganda shared by Qatari-owned Al Jazeera that, instead of displaying the savagery of October 7th in Israel, airs clips of Hamas terrorists nuzzling Jewish babies?

As The New Yorker so capably reported, much of the Arab audience is seeing heroic and compassionate fighters, as Al Jazeera displays them. In one oft-downloaded clip, the so-called “bismillah” video, a terrorist vigorously pats the back of a crying baby pressed against his shoulder—the same shoulder carrying his Kalashnikov.

“Another fighter, wearing a camouflage uniform, bandages the foot of an Israeli boy of toddler age, then puts the boy on his lap while jerking the crying baby back and forth in a stroller,” the magazine reported. “A camera zooms in on the confused face of the boy as an unseen fighter, speaking broken English, instructs him to repeat the Arabic word meaning ‘in the name of God.’ ‘Say bismillah,’ the fighter says. The boy complies, in a soft Hebrew accent.”

Experts quoted by The New Yorker derided such clips as ham-fisted propaganda. Michael Milshtein, a retired Israeli intelligence official, told the magazine that the bismillah video “demonstrates Hamas’s arrogance toward the West—that they think all Westerners are stupid, that, if they show images of these barbarian terrorists holding babies and hugging them, people in the West will say, ‘Oh, they are so sweet. We were wrong about them!’ It’s ridiculous.”

But the cruel nonsense gains traction in much of the Arab world. Ghaith al-Omari—a former adviser to the Palestinian Authority and a longtime opponent of Hamas—told the magazine that such videos had convinced many Arabs that the group’s fighters, unlike ISIS, “are humane and respect Islamic laws of war.” He added, “It has resonated throughout the Arab world. This is now the line you see not only in Hamas media but in most Arab media, in Jordan, Egypt, and North Africa. The dominant narrative has become the narrative of Hamas.”

Indeed, to Palestinians and other Arabs, the crass video hit the target. “It was posted to Al Jazeera’s Facebook page for Egypt, and has been viewed more than 1.4 million times,” The New Yorker reported. “Nearly seventy-five thousand viewers have liked it, and nearly three thousand have left comments, many of them admiring. One commenter praised ‘the morals of the fighters of the Islamic resistance.’”

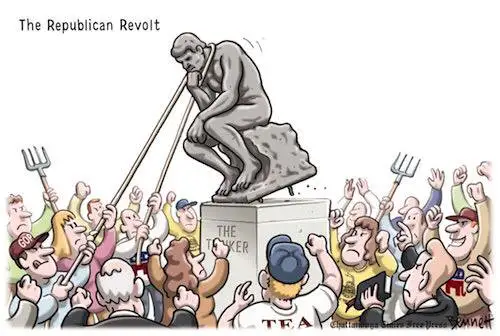

Much as American audiences can choose to view media that confirm their prejudices, the rest of the world can do so, as well. And a good part of that world isn’t seeing the truth – as best as honest journalists can discover it – but is getting propaganda, as best as Hamas and its supporters can craft it.

Misinformation abounds. The New York Times reported on how imagery from other wars is being widely circulated under headlines about the Israel-Hamas war, for example. “A heap of dead children swaddled in white, described as Palestinians killed by Israeli forces. (In fact, the children are Syrian and the photograph was taken in 2013.),” the Times recounted. “A young boy trembling in the dark, covered in a white residue and grasping a tree, cast as ‘another traumatized child in Gaza.’ (In fact, the video was taken after a recent flood in Tajikistan.)”

For the most part, major Western news outlets have been careful to check the imagery and information they get and they avoid publicizing it. However, some have been embarrassed by revelations that they employed photographers who were cheerleaders for Hamas. CNN and AP, for instance, used freelancer Hassan Eslaiah, who provided video from the October 7th attack, suggesting he went along for parts of the ghastly ride.

“He captured images of a burning Israeli tank and filmed the terrorist infiltrators entering Kibbutz Kfar Azza, as can be seen in a video,” according to National Review. In Arabic, Eslaiah said: “Everyone who were inside this tank were kidnapped, everyone who were inside the tank were kidnapped a short while ago by al-Qassam Brigades [Hamas’ armed wing], as we have seen with our own eyes.”

After an image of Eslaiah being kissed by a Hamas leader was distributed by HonestReporting, a pro-Israel outlet, both CNN and AP cut ties to him. Earlier, The New York Times was outed for using the work of Soliman Hijjy, a photographer who had been fired by the outlet a while ago because he had praised Hitler on social media. It’s not clear if the paper still uses his work, as his last archived efforts came around the time his rehiring drew critical headlines. That work perpetuated the fiction that an Israeli missile had hit the Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza.

Beyond such partisan efforts and misinformation, getting true representations is tougher in this war because of AI-generated imagery that goes beyond crude Photoshopped efforts. Reuters reported, for instance, about how a photo of Atletico Madrid fans purportedly displayed a giant Palestinian flag. It was a fake. Similarly, Reuters fact checkers turned up a false image of Argentinian soccer star Lionel Messi holding such a flag.

Much of this is spread via social media, particularly on X, formerly known as Twitter. As RFA (Radio Free Asia) reported, a “verified user” on X falsely claimed that The Wall Street Journal had reported that U.S.-made bombs were dropped on Gaza’s AI-Ahli Hospital. This lie got nearly six times more views than the newspaper’s genuine tweet about the story earlier that day. (RFA is a U.S. government-funded news outlet whose Asia Fact Check Lab seeks to expose disinformation).

In Indonesia, which has the world’s largest Muslim population, misinformation is rife. Voice of America, another U.S.-government information service, found that millions there watched a video on X entitled “Armed Hamas men infiltrate an Israeli music festival using a paraglider and launch a massive attack resulting in numerous casualties.” As VOA reported, the video was later revealed to depict Egyptian paratroopers flying over the Egyptian Military Academy in Cairo.

Given all the distortions, it’s no wonder tens of thousands came out on Armistice Day, Nov. 11, to march in London, calling for “Freedom for Palestine.” While police pegged the size of the crowd at 300,000, organizers claimed 800,000, likely another example of misinformation.

A day later, in Paris, a crowd estimated by police to total 105,000 marched with leading French politicians to decry the wave of antisemitism that has gripped France. The country has recorded more than a thousand incidents since October 7th, including the stabbing a Jewish woman in her home in Lyon. Antisemitic incidents have also occurred in Austria, Germany and Spain.

The raft of antisemitic incidents around the world gives the lie to the distinction some intellectuals make between antisemitism and anti-Zionism. How can slurs or physical attacks on Jewish institutions and on Jews be regarded as criticisms of Zionism, but not of Jews? They are one and the same.

As the Israel-Hamas war proceeds, sorting the real from the unreal will be an ongoing challenge. And, to defenders of terrorism, the facts may not matter much. They all too easily can rationalize away the existence of Hamas tunnels beneath apartment buildings and hospitals, perhaps seeing them as desperate measures by desperate people.

But it is sheer hypocrisy for the terrorists to prevent civilians from leaving areas when the Israel Defense Forces have told them to leave because of planned attacks. It seems the group values Palestinian deaths more than lives, seeing their own people as props in grisly propaganda.

Their lack of value for life in general is clear in documents found on the bodies of terrorists who attacked on October 7th. As The Washington Post reported, in one kibbutz town a dead terrorist carried a notebook with hand-scrawled Quranic verses and orders that read, “Kill as many people and take as many hostages as possible.”

Intelligence officials, piecing together tidbits such as that, have concluded that Hamas planned “not just to kill and capture Israelis, but to spark a conflagration that would sweep the region and lead to a wider conflict.” The group, apparently seeking just the sort of bloodshed now seen in Gaza, wanted “to strike a blow of historic proportions, in the expectation that the group’s actions would compel an overwhelming Israeli response.”

It is all rather sadly reminiscent of the title of a book about jihadists in Britain published a few years ago. The title: “We Love Death as you Love Life.” The quote hails from interviews given in 2014 by a pair of Hamas leaders: Muhammad Deif said: “Today you [Israelis] are fighting divine soldiers, who love death for Allah like you love life, and who compete among themselves for Martyrdom like you flee from death.” And Ismail Haniyeh said: “We love death like our enemies love life! We love Martyrdom, the way in which [Hamas] leaders died.”