A friend who worked in both newspapers and magazines recently shared a piece from The Philadelphia Inquirer whose headline a few years ago would have been shocking. It was titled “At Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, the last newsstand stopped selling newspapers.” Subhed: The explanation, sadly, is old news. Nearly no one was buying them.”

The piece, a mix of elegy and business reporting, offered a sobering slap in the face to nearly anyone of a certain age, an age when trains were filled with folks turning pages and studying the news of the day. Not so much anymore, it seems. Newspaper sales “had grown beyond bleak” at the station, the manager of the stand said. ”We weren’t making any money off newspapers.”

The piece explained how the Age of Smartphones has rendered the print product nearly obsolete, quaint perhaps. It suggested that the pandemic worsened the newspaper industry’s existential struggle with the digital world. And it discussed how newsstands themselves are vanishing, much as coin-operated news boxes are.

“Each year an estimated four million passengers pass through the station’s soaring concourse, making it Amtrak’s third busiest hub,” the Inquirer reported. “Meanwhile, in recent times, the stand rarely sold more than a dozen daily papers each day … Then there’s rising prices, delivery costs, and time and energy spent bundling up returns.”

Tillman Crane photo, source: The Philadelphia Inquirer

The piece included a photo of another newsstand in the center of the concourse, a memorable shot that for a time even hung in the National Art Museum of China. In its haunting emptiness and ghostly lighting, that photo to me is reminiscent of an Edward Hopper painting. Even as it is foregrounded with stacks of newspapers waiting to be snapped up by news-hungry travelers, the shot seems a bit funereal, foreshadowing the fate of print decades after photographer Tillman Crane aimed his camera at the stand in 1989.

This is not news, of course. Almost since my first days in the news business, back in the summer of 1974, industry changes have been extraordinary, with many of them seeming like campaigns in a war against obsolescence. My first job, in the noisy back shop of a New Jersey daily with hot-type lead Linotype machines behind me, was as a proofreader. Three colleagues and I would comb sheets of typescript for typos that we circled and dispensed to the editors in the busy newsroom. Copy moved between us and that newsroom on an overhead conveyor belt on sheets of rough paper.

That job was obsoleted soon by computers on which reporters and editors did their own proofing. And the compositors, who operated the linotypes, soon enough lost their jobs, as systems bypassed those noisy, dirty and dangerous machines.

By the time I made it into the newsroom – first as a copyboy and then as a reporter – IBM Selectrics were giving way to fancy typewriter-like systems that allowed us to more efficiently type copy to be scanned and ultimately printed. Then, in the blink of an eye, we moved to computer terminals and the newsroom became far quieter.

Still more changes awaited us during my six years at the paper, then called The Home News. We scrapped a traditional layout in favor of a trendy modular design. The old classic look went the way of the afternoon edition of the paper (which I had delivered as a kid not many years before). TV obsoleted that edition.

Source: Society of Professional Journalists

Later, after grad school in 1980-81, I saw a similar makeover at Denver’s Rocky Mountain News, where I spent another six years. At both papers, modernization seemed essential if we were to hang onto readers and we hung out hats on cosmetic changes.

Still later, when I began my 22-year stint at BusinessWeek, my editors put the magazine through several similar technological and esthetic changes. New looks to “the book” and new machines to move the information more efficiently between reporters and editors were a regular thing. We had to stay au courant and we did so relentlessly, making oodles of money for McGraw-Hill in the process – until, suddenly, we didn’t anymore.

As the Net ramped up in the aughts – and especially after one of the big tech ad busts — we tried to adjust by serving up information many times daily – not just weekly anymore. We built an ambitious Internet news operation, along with the reporting by magazine folks. It was all very pricey and all, in hindsight, rather desperate – as desperate as the efforts of those compositors at The Home News to preserve their jobs against the march of technology.

McGraw-Hill, weary of losing money on BW, sold it for a song to Bloomberg in 2009. And today, Bloomberg Businessweek still offers a print product. But, just as Forbes, Fortune, Time and Newsweek have declined in importance, BBW seems less consequential. I’m not sure it’s even sold on newsstands anymore, though it is available by subscription.

With the power of Bloomberg News behind it, the magazine should be a dynamo. But it feels to me as if its glory days are behind it, at least in its magazine form. Indeed, Poynter last year reported that BBW’s print circulation had dropped from nearly one million in 2012 to 316,000 at the end of 2021. Perhaps the $399 a year cost for an all-access subscription has something to do with that. Perhaps it’s just that the proliferation of information on the Net has made all but a few news-outlet brands almost irrelevant.

Newspapers, of course, have been dying fast. And even as innovative online news operations all across the country arise to try to fill the gaps, the changes in the industry seem overwhelming, obsoleting many operations and depriving people of sorely needed news. Even as brands such as The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal are doing okay (despite recent layoffs at the WaPo), local news has taken it most on the chin.

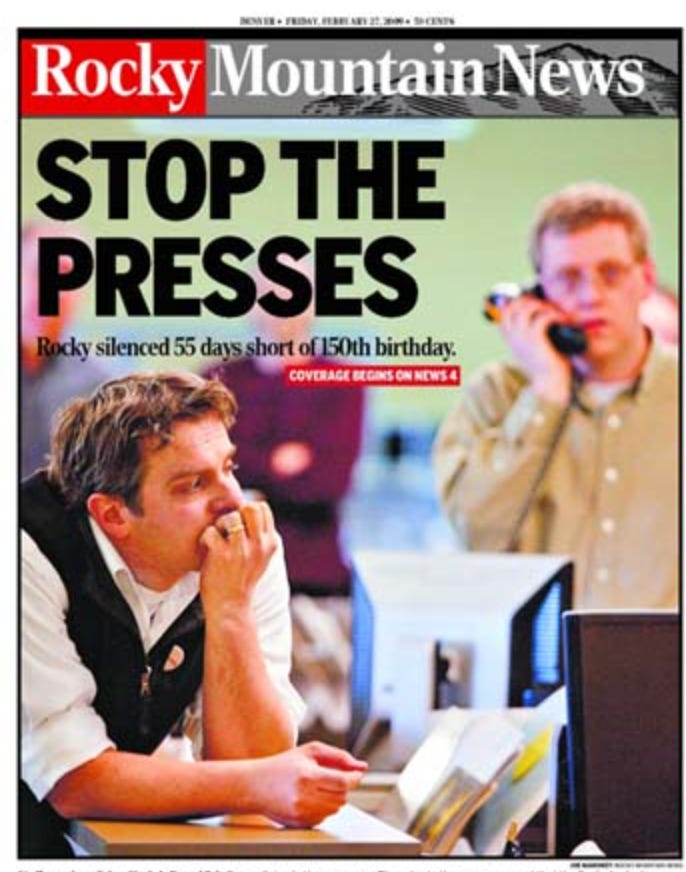

My old paper, The Home News, was folded into something called the Home News Tribune, a Gannett product available through my central jersey. The paper survives, at least, unlike the Rocky Mountain News, which bit the dust in early 2009 (Ironically at around the same time I gave notice at BW as I moved to become an academic).

For all my time in it, change has been the lot of the news industry. The arc rose and fell for the business and the drive to stay ahead of the reaper was a troubling one as that arc turned downward. Today, it’s sad to see the end of sales of newspapers at that Philly newsstand as the trend draws toward its logical conclusion.

Of course, some digital news outlets continue to thrive. The Inquirer serves readers electronically, as do so many other outlets, including Bloomberg. They all innovate relentlessly, as they must. But will they stay ahead of the reaper? As they used to say in TV, stay tuned.