Nineteen years after breaking free of the collapsed Soviet Union, Kazakhstan remains one of capitalism’s last frontiers. From its nascent stock exchange in the financial and commercial center of Almaty to the sprawling Abu Dhabi-like construction and institution-building under way in the capital city of Astana, the country continues to seek its footing economically. Its mixture of private enterprise and state direction, together with a benevolent strongman’s rule, would make the place a fascinating laboratory for an economist.

Nineteen years after breaking free of the collapsed Soviet Union, Kazakhstan remains one of capitalism’s last frontiers. From its nascent stock exchange in the financial and commercial center of Almaty to the sprawling Abu Dhabi-like construction and institution-building under way in the capital city of Astana, the country continues to seek its footing economically. Its mixture of private enterprise and state direction, together with a benevolent strongman’s rule, would make the place a fascinating laboratory for an economist.

There’s no question that Kazakhstan is the economic powerhouse of Central Asia, the richest of the “stans” and the most politically stable. Its oil wealth in the Caspian Sea has already been staked out by China, Russia and the Western countries, especially the U.S. They covet its huge fields of reserves as strategically vital alternatives to Mideastern suppliers. About as big as Western Europe and far less populated, the country also boasts hefty supplies of uranium and just about every other mineral developed societies need.

And yet, it has a long way to go to be a fully formed modern capitalist state. For one thing, many residents still live in crumbling Soviet-era concrete apartment blocks that can stink of sewage, and feature dark cement staircases with missing windows and poorly planned and maintained common areas. Our apartments in gleaming, modern Astana would be low-end by South Bronx standards. Lines of trash bins next to playgrounds invite vermin hard by spots where kids play. The play area, surrounded by our five-story apartment buildings, is a vivid demonstration of the tragedy of the commons – overgrown and decaying with apparently no one to maintain it or at least to maintain it well. Similar buildings linger in Almaty, as in this photo of one sprawling tower block. (Click on it to see detail).

And yet, it has a long way to go to be a fully formed modern capitalist state. For one thing, many residents still live in crumbling Soviet-era concrete apartment blocks that can stink of sewage, and feature dark cement staircases with missing windows and poorly planned and maintained common areas. Our apartments in gleaming, modern Astana would be low-end by South Bronx standards. Lines of trash bins next to playgrounds invite vermin hard by spots where kids play. The play area, surrounded by our five-story apartment buildings, is a vivid demonstration of the tragedy of the commons – overgrown and decaying with apparently no one to maintain it or at least to maintain it well. Similar buildings linger in Almaty, as in this photo of one sprawling tower block. (Click on it to see detail).

But in Astana people live in Soviet-era blocks, spread across the old area of the city, because the apartments were given to them free in the Soviet days. Even now, many can’t afford the stunning new buildings still under construction in the newer parts of the city. That housing is being privately developed and sold. Instead, people borrow to buy pricey cars – Mercedes-Benzes, Lexuses, Range Rovers and others dominate the jammed roads here. One of our guides says Kazakh people like to “show off” and they often go deeply into debt to drive glitzy cars. They also crave glitzy western brand names, as Gucci stores in Almaty suggest.

But in Astana people live in Soviet-era blocks, spread across the old area of the city, because the apartments were given to them free in the Soviet days. Even now, many can’t afford the stunning new buildings still under construction in the newer parts of the city. That housing is being privately developed and sold. Instead, people borrow to buy pricey cars – Mercedes-Benzes, Lexuses, Range Rovers and others dominate the jammed roads here. One of our guides says Kazakh people like to “show off” and they often go deeply into debt to drive glitzy cars. They also crave glitzy western brand names, as Gucci stores in Almaty suggest.

Certainly, people will occupy those shiny new buildings over time, though. The country is developing a solid middle class of well-schooled professionals, managers and state bureaucrats who will take to the new residences once their resources allow it. If nothing else, supply and demand will drop the prices of the new condos, one would think. The construction, driven by a real estate bubble that popped a couple years ago, still lumbers along, albeit at a slower rate.

It’s hard to imagine, much less portray, the extent of new development, particularly in Astana. The city was rechristened as the nation’s capital only in 1997 by President Nazarbaev, and it has risen into a Disneyland-like sprawl of some of the most ingenious and playful architecture in the world. In the new city centre, as it is called, a glass and steel pyramid rises near towering office buildings shot through with arches and sporting clever overhangs or minarets. Bright pastels reflect the sun. Even amid the slowdown, building cranes still dominate the skyline behind billboards that hawk the luxury living promised by the novel structures. It’s as if the whole place is a World’s Fair.

It’s hard to imagine, much less portray, the extent of new development, particularly in Astana. The city was rechristened as the nation’s capital only in 1997 by President Nazarbaev, and it has risen into a Disneyland-like sprawl of some of the most ingenious and playful architecture in the world. In the new city centre, as it is called, a glass and steel pyramid rises near towering office buildings shot through with arches and sporting clever overhangs or minarets. Bright pastels reflect the sun. Even amid the slowdown, building cranes still dominate the skyline behind billboards that hawk the luxury living promised by the novel structures. It’s as if the whole place is a World’s Fair.

We visited the Eurasian National University on Thursday. The gorgeous facilities, housing a museum that showcases ancient artifacts of the region’s earliest days and paintings of warrior heroes of old, are part of a university created by the president to train future leaders, many in the ways of the West. The president also set up a national scholarship program that sends young students to study abroad, so long as they return to help modernize Kazakhstan. Leaders in the journalism school at the university asked us if we could host students at UNL and develop an educational collaboration – something that I am sure our folks would be keen to do.

Our meeting was almost like an affair of state. We all gathered on one side of a table of microphones and the J School faculty gathered on the other. My name was printed on a card, as was that of the J School director opposite me. A small Kazakhstan flag stood before him on the table, and a small American flag stood before me. The session began with rather formal speeches of welcome, all run through a translator from the U.S. Embassy. (The embassy is a stunning new building, corner of America behind some tight security. Very welcoming folks there, too).

Soon enough at the J School, we got down to finding common ground. Since my colleague, Bruce Thorson, and I and the Kazakh faculty were all about the same age, we bemoaned the lack of reading by our Internet-driven students and fretted over the future of print. I got the feeling, however, that preparing students to deliver Net-ready material is not on their agenda here – yet. A meeting with a newspaper editor later confirmed this, as he complained of declining readership but also said he hoped the Net wouldn’t usurp print journalism until he was ready to retire. He, too, is ahem, of a certain age.

Yesterday, some of the students and I went to a stunning mosque with a helpful guide who counted herself as a far-too-unobservant Muslim. Men and women prayed together in the mosque, unlike the more traditional mosque we visited in Almaty. I was able to sit with the group as an imam led prayers. And, to the dismay and disgust of our hostess, some women walked in sporting short skirts. Islam light seems to prevail here.

Yesterday, some of the students and I went to a stunning mosque with a helpful guide who counted herself as a far-too-unobservant Muslim. Men and women prayed together in the mosque, unlike the more traditional mosque we visited in Almaty. I was able to sit with the group as an imam led prayers. And, to the dismay and disgust of our hostess, some women walked in sporting short skirts. Islam light seems to prevail here.

Afterward, we went to the Lubavitch-run synagogue, Beit Rachel. The shul is in a beautiful building that features a gleaming Star of David on its roof, much like churches showcase crosses – and far more showy than most shuls in America. Nonetheless, it is fenced off, unlike mosques, and has a security guard in a booth at the entrance. Much as religious tolerance is the rule here, Jews have reason to be cautious, it seems. There is also a large Catholic church in town. At Beit Rachel, young Israelis urged me to lay tefillin, which I did. We all had imposed on them a bit, with a local TV crew running all about the building filming us as we did our photojournalism there.

On Saturday, I went to services where, sadly, there were just a yeshiva boker who spoke only Hebrew, a couple other guys who spoke Russian and one delightful fellow from Baku, who spoke English. I’m told more people come when the rabbi is in town, but he’s in Israel at the moment. Still, it was fun talking with the Azeri fellow and it was a delight to eat cholent, the first meat I’ve (knowingly) had in a few weeks. We had a pleasant time all around and got an Amidah or two in.

On Saturday, I went to services where, sadly, there were just a yeshiva boker who spoke only Hebrew, a couple other guys who spoke Russian and one delightful fellow from Baku, who spoke English. I’m told more people come when the rabbi is in town, but he’s in Israel at the moment. Still, it was fun talking with the Azeri fellow and it was a delight to eat cholent, the first meat I’ve (knowingly) had in a few weeks. We had a pleasant time all around and got an Amidah or two in.

Further on the religious front, a group of us on Friday also visited a pyramid where all the world’s religions are celebrated. Conferences there periodically draw global religious leaders to talk about their differences and similarities. It’s part of the president’s vision for a harmonious world. I’m told the Pope is among major world religious leaders who have stopped by.

Religiously and financially, there’s a sense of freshness and newness about the country. It’s as if it is still discovering itself and its role in the world, even as it celebrates its ancient history. It also needs to carefully walk lines, balancing Russia, China and the U.S., as well as keep religious and ethnic differences from becoming problems. It is enjoying — but must be cautious about — the billions of dollars, renminbi and rubles that have poured into place in the last 15 years or so. Its institutions are hard-put to keep pace.

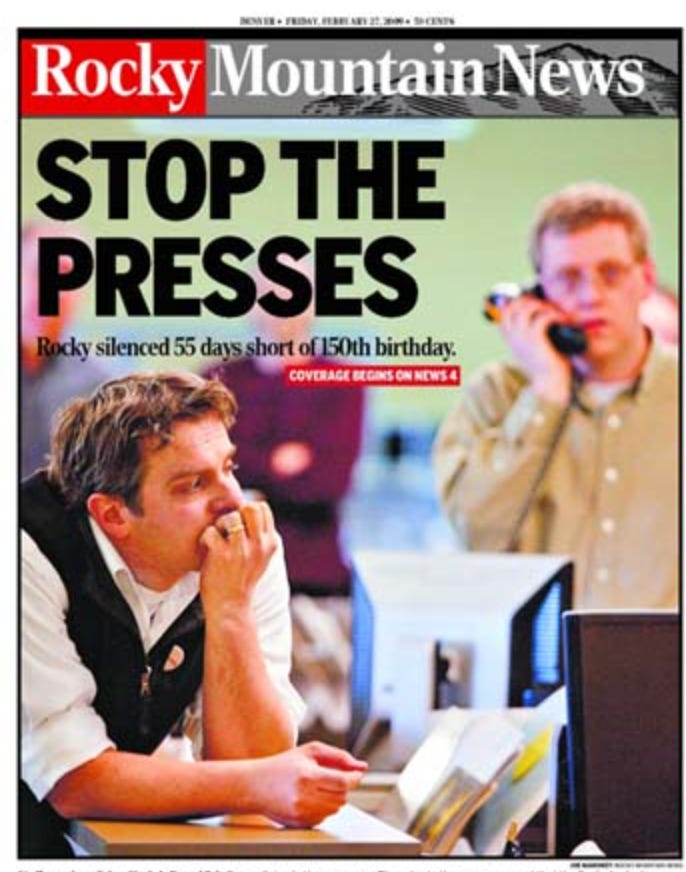

Perhaps the best example is the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange. Set up two days after the country’s currency, the Tenge, was introduced in 1993, KASE is the home bourse for 121 companies. Like markets the world over, these outfits have been roller-coasting in recent years. After soaring past $96 billion in 2008, the market capitalization of the exchange members plunged to about $25 billion last year before recovering to about $64 billion now. The volatility reflects how interlinked Kazakhstan’s economy is with the world’s. The market is still comparatively small and, though heavily electronic, maintains a cubicle-filled trading floor, as the photo here by Sarah Tenorio shows.

Perhaps the best example is the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange. Set up two days after the country’s currency, the Tenge, was introduced in 1993, KASE is the home bourse for 121 companies. Like markets the world over, these outfits have been roller-coasting in recent years. After soaring past $96 billion in 2008, the market capitalization of the exchange members plunged to about $25 billion last year before recovering to about $64 billion now. The volatility reflects how interlinked Kazakhstan’s economy is with the world’s. The market is still comparatively small and, though heavily electronic, maintains a cubicle-filled trading floor, as the photo here by Sarah Tenorio shows.

As one might expect, oil and mining companies dominate the exchange. But banking and finance is important, too. And all these outfits rise and fall based on global conditions. The finance sector here went into free fall, with lots of bank defaults, because banks here had borrowed heavily from global banks. Real estate, which boomed in U.S. fashion, collapsed amid overextension, leaving Almaty with lots of unfinished buildings. Luxury homes in a neighborhood called Luxor near the KASE offices were going for $4 million in 2008 and they have since fallen by half that.

Still, Kazakhstan’s mineral wealth should sustain the country as long as the world continues to need oil, uranium and other crucial materials. What’s more, the nation’s leaders are keen to diversify the economy to avoid overdependence on such resources. Tourism, for instance, is an area they would much like to expand. If they can improve their hotels and tourist infrastructure, there’s no reason they can’t make a go of it.

Over time, this country’s development will be fascinating to watch.