Looking for ways to make business journalism come alive for students? How about creating scavenger hunts for juicy tidbits in corporate government filings? What about mock press conferences that play PR and journalism students against one another? Then there are some sure bets – awarding $50 gift cards to local bars for mock stock-portfolio performances and showing students how to find the homes and salaries of university officials and other professors – including yourself — on the Net.

Looking for ways to make business journalism come alive for students? How about creating scavenger hunts for juicy tidbits in corporate government filings? What about mock press conferences that play PR and journalism students against one another? Then there are some sure bets – awarding $50 gift cards to local bars for mock stock-portfolio performances and showing students how to find the homes and salaries of university officials and other professors – including yourself — on the Net.

These were among the ideas savvy veteran instructors offered at the Business Journalism Professors Seminar last week at Arizona State University. The program, offered by the Donald W. Reynolds National Center for Business Journalism, brought together as fellows 15 profs from such universities as Columbia, Kansas State, Duquesne and Troy, as well as a couple schools in Beijing, the Central University of Finance & Economics and the University of International Business and Economics. I was privileged to be among those talented folks for the week.

We bandied about ideas for getting 20-year-olds (as well as fellow faculty and deans) excited about business journalism in the first place. The main answer was, of course, jobs. If they’d like good careers in journalism that pay well, offer lots of room to grow and that can be as challenging at age 45 as at 20, there really are few spots in the field to match. These days, with so much contraction in the field, business and economic coverage is one of the few bright spots, with opportunity rich at places such as Reuters, Bloomberg News, Dow Jones and the many Net places popping up.

The key, of course, is to persuade kids crazy for sports and entertainment that biz-econ coverage can be fun. The challenge is that many of them likely have never picked up the Wall Street Journal or done more than pass over the local rag’s biz page. The best counsel, offered by folks such as UNC Prof. Chris Roush, Ohio University’s Mark W. Tatge, Washington & Lee’s Pamela K. Luecke and Reynolds Center president Andrew Leckey, was to make the classes engaging, involve students through smart classroom techniques and thus build a following. Some folks, such as the University of Kansas’ James K. Gentry, even suggest sneaking economics and (shudder) math in by building in novel exercises with balance sheets and income statements.

The key, of course, is to persuade kids crazy for sports and entertainment that biz-econ coverage can be fun. The challenge is that many of them likely have never picked up the Wall Street Journal or done more than pass over the local rag’s biz page. The best counsel, offered by folks such as UNC Prof. Chris Roush, Ohio University’s Mark W. Tatge, Washington & Lee’s Pamela K. Luecke and Reynolds Center president Andrew Leckey, was to make the classes engaging, involve students through smart classroom techniques and thus build a following. Some folks, such as the University of Kansas’ James K. Gentry, even suggest sneaking economics and (shudder) math in by building in novel exercises with balance sheets and income statements.

Once you have the kids, these folks offered some cool ideas for keeping their interest:

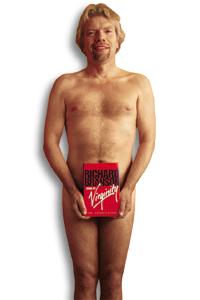

— discuss stories on people the students can relate to, such as the recent Time cover on Mark Zuckerberg or the May 2003 piece in Fortune on Sheryl Crow and Steve Jobs, and make sure to flash them on the screen (at the risk of offending the more conservative kids, I might add the seminude photo BW ran of Richard Branson in 1998)

— scavenger hunts. Find nuggets of intriguing stuff in 10Ks or quarterly filings by local companies or familiar outfits such as Apple, Google, Coca-Cola, Buffalo Wild Wings, Hot Topic, The Buckle, Kellogg, etc., and craft a quiz of 20 or so questions to which the students must find the answers

— scavenger hunts. Find nuggets of intriguing stuff in 10Ks or quarterly filings by local companies or familiar outfits such as Apple, Google, Coca-Cola, Buffalo Wild Wings, Hot Topic, The Buckle, Kellogg, etc., and craft a quiz of 20 or so questions to which the students must find the answers

— run contests in class to see who can guess a forthcoming unemployment rate, corporate quarterly EPS figure or inflation rate

— compare a local CEO’s pay with that of university professors, presidents or coaches, using proxy statements and Guidestar filings to find figures

— conduct field trips to local brokerage firm offices, businesses or, if possible, Fed facilities

— have student invest in mock stock portfolios and present a valuable prize at the end, such as a gift certificate or a subscription to The Economist (a bar gift card might be a bit more exciting to undergrads, I’d wager)

— follow economists’ blogs, such as Marginal Revolution and Economists Do It With Models, and get discussions going about opposing viewpoints

— turn students onto sites such as businessjournalism.org, Talking Biz News, and the College Business Journalism Consortium

— have students interview regular working people about their lives on the job

— discuss ethical problems that concern business reporters, using transgressors such as R. Foster Winans as examples. Other topics for ethical discussions might include questions about taking a thank-you bouquet of flowers from a CEO or traveling on company-paid trips, as well dating sources or questions about who pays for lunch

— discuss business journalism celebs, such as Lou Dobbs and Dan Dorfman

— discuss scandals such as the Chiquita International scandal (Cincinnati Enquirer paid $10 m and fired a reporter after he used stolen voicemails)

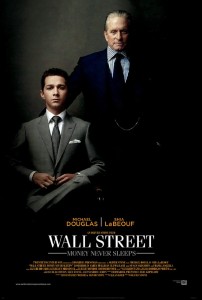

— use films such as “The Insider,” “Wall Street,” and “Social Network” to discuss business issues

— use short clips from various films to foster discussions of how businesses operate. Good example: “The Corporation”

— team up with PR instructors to stage a mock news conference competition pitting company execs in a crisis against journalism students. Great opportunity for both sides to strut their stuff.

We also heard helpful suggestions from employers, particularly Jodi Schneider of Bloomberg News and Ilana Lowery of the Phoenix Business Journal, along with handy ideas from Leckey and Reynolds executive director Linda Austin, a former business editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer. My biggest takeaway: run some mock job interviews with students and teach them to send handwritten thank-you notes.

And we were treated to some smart presentations by journalists Diana B. Henriques of the New York Times about the art of investigative work (look for her new Madoff book), the University of Nevada’s Alan Deutschman about the peculiar psychologies of CEOs (narcissists and psychopaths are not uncommon), the University of Missouri’s Randall Smith’s view of the future for business journalists (it’s raining everywhere but less on business areas). We got some fresh takes on computer-aided reporting, too, by Steve Doig of the ASU Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication as well as on social media by the Reynolds Center’s Robin J. Phillips.

For anyone interested in journalism, especially biz journalism, it was a great week. As I take the lessons from ASU to heart, my students will be better off. My thanks to the folks there.