The letter was short, barely filling a page. But the message, for me, was a big deal. The vice chancellor for academic affairs at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln let me know this week that I had successfully run a 5 ½-year long gauntlet and qualified for tenure.

The letter was short, barely filling a page. But the message, for me, was a big deal. The vice chancellor for academic affairs at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln let me know this week that I had successfully run a 5 ½-year long gauntlet and qualified for tenure.

I choked up. I felt like a 17-year-old getting accepted into the college of his dreams. The news about what technically is called “continuous appointment” meant more to me than I had expected. It meant more than just job security; it meant I had been accepted by my peers, my dean and the people who fill the upper reaches of my Big Ten university as someone they’d like to work with for as long as I could command a podium in a classroom.

That acceptance, that ratification of my role as a mentor to young people, that endorsement of my teaching and research skills – it was like getting my first car or going on a first date. It summoned up sepia-colored images of my father – someone who had not even graduated from high school – calling me and an academically inclined sister his little professors. We were the ones who pulled As, the ones he could see in classrooms, occupying places he respected.

I was surprised at my own reaction, though, partly because I’ve been conflicted about tenure. After all, I managed to stay 22 years at my last job, at BusinessWeek, without it, and had worked at three other news organizations before without it. At each place, I was only as good – and secure – as my next story. My job security depended on shifting arrays of bosses and the economic health of my employer. And that seemed fine to me – even just, if one believes healthy capitalism requires dynamic labor markets where jobs must come and go, where there is no room for sinecures.

For years I’ve been sympathetic to a view that a former colleague at BusinessWeek put into writing recently. Sarah Bartlett, marking her first anniversary as dean of the Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York, complained that the “tenure system can create a permanent class of teachers who may not feel much pressure to constantly refresh their skills or renew their curricula.” Tenure, she suggested, would atrophy programs rather than create the “vibrant academic cultures” that journalism schools, in particular, need at a time of great industry ferment.

But does tenure serve mainly to shield those who would resist change? Does it do little more than protect aging old bulls and cows who should long ago have been turned out to pasture? Does it guarantee that hoary old fossils will dominate classrooms, spouting outdated and irrelevant approaches? Does the pursuit of tenure, moreover, drive aspiring faculty members to do pointless impractical research that doesn’t help the journalism world or the J schools themselves, as Sarah also implied?

But does tenure serve mainly to shield those who would resist change? Does it do little more than protect aging old bulls and cows who should long ago have been turned out to pasture? Does it guarantee that hoary old fossils will dominate classrooms, spouting outdated and irrelevant approaches? Does the pursuit of tenure, moreover, drive aspiring faculty members to do pointless impractical research that doesn’t help the journalism world or the J schools themselves, as Sarah also implied?

Well, I look around at my tenured colleagues at UNL and see the opposite. As one pursued tenure, she wrote a textbook for training copy editors. Sue Burzynski Bullard’s text – “Everybody’s An Editor: Navigating journalism’s changing landscape” – should be standard fare in any forward-looking J school. Because it is an interactive ebook, the now-tenured Bullard is able to – and does – refresh the book regularly. Another colleague, John R. Bender, regularly updates “Reporting for the Media,” an impressive text that he and three colleagues wrote. It’s now in its 11th edition. A third colleague, Joe Starita, produced “I Am A Man: Chief Standing Bear’s Journey for Justice,” setting a high bar for storytelling and research that contributes to an emphasis at our school in journalism about Native Americans. This was Starita’s third book and he’s toiling on a fourth, even as he inspires students in feature-writing and reporting classes.

And that productivity by tenured faculty isn’t limited to written work. Starita teamed up with multimedia-savvy journalism sequence head Jerry Renaud to shepherd the impressive Native Daughters project about American Indian women. Bernard R. McCoy, a colleague who teaches mainly (but not exclusively) in the broadcasting sequence, has produced documentaries including “Exploring the Wild Kingdom,” a public-TV effort about the most popular wildlife program in television history. Another of his works, “They Could Really Play the Game: Reloaded,” tells the story of an extraordinary 1950s college basketball team. And he’s now working on a production about WWI Gen. John J. Pershing.

Tenure doesn’t mean that creative work ends or innovations in the classroom cease. Each of my colleagues has had to adapt to the digital world. Some still prefer to teach in older ways – one quaintly requires students to hand in written papers that he grades by hand, for instance. But even he teams up with visually oriented colleagues to guide students to produce work as today’s media organizations demand it. Charlyne Berens, a colleague, and I teamed up with the Omaha World-Herald just last spring to guide students to produce a 16-part series that boasts print, online and multimedia elements, The Engineered Foods Debate. Charlyne, who recently retired as our associate dean, wrote several works, including “One House,” about the peculiar unicameral Nebraska legislature, and another about the former Secretary of Defense, “Chuck Hagel: Moving Forward.”

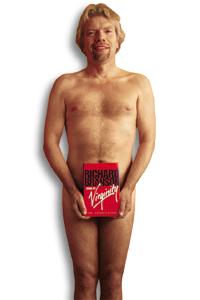

As for me, the pursuit of tenure gave me the impetus to write my first book, “Transcendental Meditation in America: How a New Age Movement Remade a Small Town in Iowa.” I’m now working on a second book, exploring the reasons that drive people to join cults. I’m also developing curricula for business and economic journalism instruction that I hope will serve business school and J school students, including those interested in investor relations. The pursuit of tenure also drove me to develop research for academic journals, encouraging me to look into areas as far-flung as journalism training in China, as well as such practical work as the teaching of business journalism, the challenges of teaching fair-minded approaches to aspiring journalists, and the pros and cons of ranking journalism schools – all topics for forthcoming journal publication.

As for me, the pursuit of tenure gave me the impetus to write my first book, “Transcendental Meditation in America: How a New Age Movement Remade a Small Town in Iowa.” I’m now working on a second book, exploring the reasons that drive people to join cults. I’m also developing curricula for business and economic journalism instruction that I hope will serve business school and J school students, including those interested in investor relations. The pursuit of tenure also drove me to develop research for academic journals, encouraging me to look into areas as far-flung as journalism training in China, as well as such practical work as the teaching of business journalism, the challenges of teaching fair-minded approaches to aspiring journalists, and the pros and cons of ranking journalism schools – all topics for forthcoming journal publication.

Forgive me for beating my own chest. I don’t mean to. I am humbled by the work that my colleagues at the J school and across the university do. It is an enormous honor for them to consider me a peer and, assuming that the university’s regents in September agree with our vice chancellor, I expect that I will spend the next decade or so trying to live up to that.