Have the pols lost sight of the value of education in Nebraska?

Back in 2009, when I joined the journalism faculty at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, all arrows were pointing upward for the university. Enrollments were growing, buildings were rising, and graduates were going on to healthy careers in newswriting and other things. The state legislature and good citizens of the state realized that education was important, and they funded it, accordingly.

Even the Huskers won far more than they lost. The state’s football team racked up a 10-4 season that year, leading the Big 12 Northern Division and ranking 14th best in the national AP poll.

My, how things have changed.

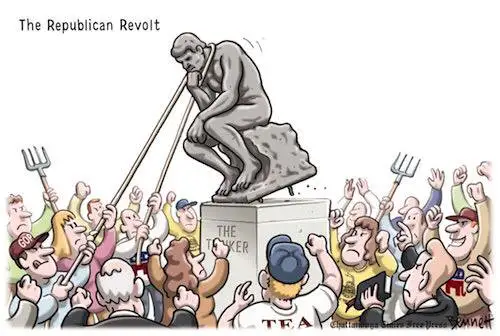

Overall enrollment at the flagship Lincoln campus has slipped from 24,100 back then to 23,600 now. Journalism is on the run, with graduates finding fewer opportunities in newspapers and other news operations. And the legislature and governor, engaged in ideological warfare with educators, seem to have forgotten that education both matters and costs.

As for the Huskers, the team seems emblematic of the university’s decline. After several pricey coach and athletic director departures, Big Red eked out a 5-7 season last year, a middling result in the Big 10 West (albeit better than the 4-8 record of the prior year). The university appears to be scrambling to avoid being kicked out of the Big 10, a lingering fear because UNL is the only conference member that doesn’t belong to the 71-member Assoc. of American Universities (the university was tossed by the AAU in 2011 over research funding issues and is trying to rejoin it).

But now the ideologues who’ve seized most of the levers of power in the state are busy chipping away at the university’s hopes and ambitions. As a former student of mine, Zach Wendling, reported for the Nebraska Examiner, the regents just approved a $1.1 billion state-aided budget for fiscal year 2025 that will require campus leaders to scrape away another $11.8 million from their budgets in the next year, after they cut about $30 million in the past two fiscal years

While that one-year 1% cut seems like a pittance, it will bite. The earlier cuts did so, with some of the most visible trims being reduced library hours and fewer graduate teaching assistants and student workers. Plans were made last fall for deep cuts in the diversity, equity and inclusion office, undergrad ed and student success programming and non-specific operational efficiency improvements.

I’m reminded of a dark joke an economist colleague at BusinessWeek once told me. “If you cut the feed of a fine thoroughbred racehorse just a little bit each month or so to save money, what do you wind up with?” The answer: “a dead horse.”

In the case of UNL, it more likely will be a hobbled one, but one that limps along, nonetheless. The new round of cuts will involve an elaborate consultation approach with faculty and administrators, so it’s not clear now where they will come from. “As we begin this work, we will utilize shared governance processes to move forward in an engaged and thoughtful way,” Chancellor Rodney D. Bennett said in a message from his office.

But cutting majors and departments with little enrollment has been vaunted as one possible approach, along with eliminating staff jobs. That has been a popular tack at several schools, including the University of North Carolina Greensboro. The University of New Hampshire, as it trims 75 staff jobs, is shutting it art museum. And closer to home, at the University of Nebraska’s Kearney campus, bachelor’s degrees in areas such as geography, recreation management and theater are slated for elimination.

At UNL, just how much university-wide consultation versus administrative fiat will be involved will be difficult to say. When the chancellor last fall proposed a 46% cut from the Office of Diversity and Inclusion and Office of Academic Success and Intercultural Services – some $800,000 – he triggered passionate objections from a good number of faculty and others. But he was pleasing the regents who had hired him last year.

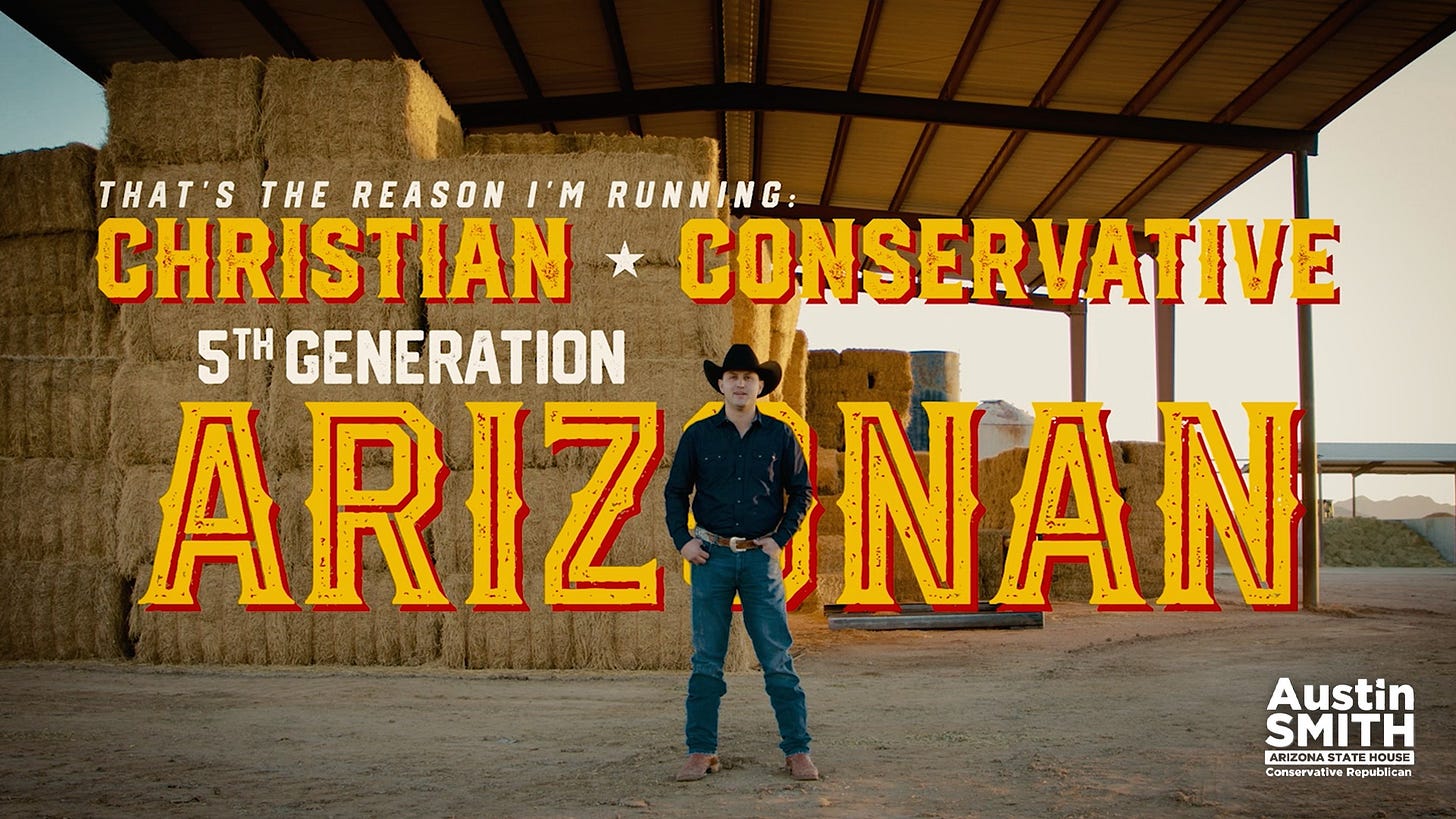

The university’s DEI efforts – like similar programs around the country – have been hot-button matters for many on the right. Indeed, the chair of the regents opposed the budget in the June 20 5-2 vote, arguing that no diversity, equity or inclusion initiatives or programs should be funded.

“We need to recruit and have folks — diversity — here, but we shouldn’t be using tax dollars to fund and promote certain races or genders above others,” said regent chair Rob Schafer. “It ought to be a fair and level and equal playing field for all.”

Asked whether he’s seen the promotion of one race or gender at NU campuses – i.e., evidence of a problem — Schafer offered a, well, incomprehensible reply. “Just the fact that we have funding and we’re promoting different things, I think there’s some things that we could just do better,” journalist Wendling reported.

While enrollments continue to be under pressure, in part because the numbers of teens in the state have been stuck at between 129,000 and 142,000 for the last dozen years, the regents seem to be operating at cross-purposes by making the school more costly. They voted to hike tuition between 3.2% and 3.4% across the system’s several campuses, on top of a 3.5% across-the-board hike they okayed last year.

Despite that, Chancellor Bennett pointed to enrollment growth this past spring. Going forward, though, it’s not clear how making something more costly will draw more customers. Perhaps the regents and administrators haven’t consulted the folks in the economics department.

The tuition hikes drew the other no vote on the budget from Kathy Wilmot, who won her elected post as regent in 2022 in part by attacking “liberal leaning” courses at the university and venting about “indoctrination” at UNL. Now, as she bemoans the planned tuition hikes, she doesn’t seem to be urging more funding from the legislature to make those hikes unnecessary.

“To me, the families have already chipped in because they’re paying the taxes and things that we turn to the Legislature and everybody for,” Wilmot said, according to Wendling. “Then, when we ask those students from those families to chip in again, I feel that’s somewhat of a double hit.”

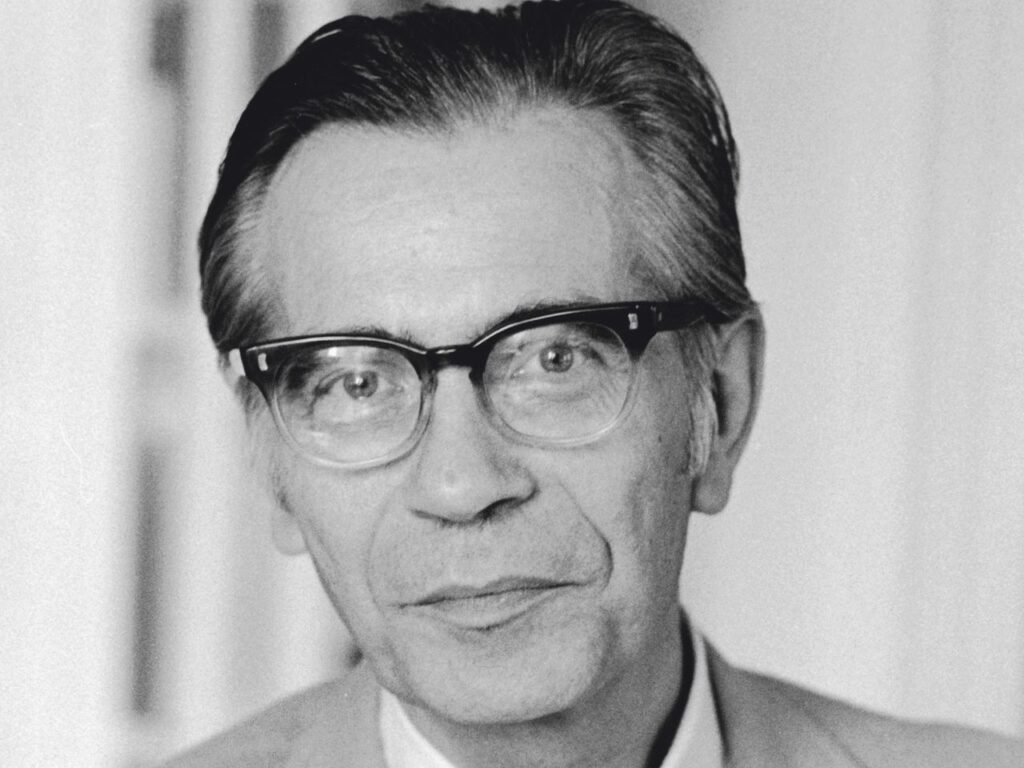

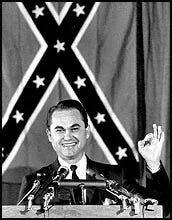

Back in the late 1960s, when the university was forming its four-campus system and the legislature generously funded the effort, a rising Republican star with a lot of influence in the state named Clayton Yeutter argued passionately for education. The schooling he got at Nebraska – including an undergrad degree, a Ph.D and a law school degree – led him from a small family farm to high levels in Washington, D.C. in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including serving as Secretary of Agriculture, U.S. Trade Representative and head of the Republican National Committee. Trained in economics, the late Yeutter understood that quality costs.

Somehow, in these polarized times, the overwhelmingly Republican leaders in Nebraska have lost sight of that. Yeutter, whose statue graces the campus, would likely be disgusted by their approaches now.