Maybe some presidential election rhetoric should not be turned down

A longstanding maxim in the news business says “information abhors a void.” When we don’t know things, or know things only partly, we rush to fill in the gaps. Often, we are wrong and, sadly, misinformation may carry enormous weight.

The latest example is the reaction to the shooting of Donald Trump. We still don’t know why a disturbed young man took up arms against the former president. But that hasn’t stopped people from blaming the fiery rhetoric of one side or the other – pleas for putting oil on the waters, notwithstanding. Indeed, the absence of information has driven those who see opportunity here into overdrive (and it’s been rich grist for the inevitable conspiracists).

Before the shooting, would-be assassin Thomas Matthew Crooks googled the phrase “major depressive disorder” and searched for information about Trump, Joe Biden, and Attorney General Merrick Garland, as we heard from The Washington Post and The New York Times. We also saw in The Times that he looked up events where Trump and Biden were speaking.

Does that mean he would have attacked whichever man was nearby? That it was just convenient that Trump was appearing not far from his home? That his motivation was less political (or partisan) and more psychological, i.e., a lost post-adolescent looking for a grandiose way to commit what is often called “suicide by police?”

We’ve seen several reports that Crooks had shown little interest in politics, though he was a registered Republican with one parent a Democrat and one a Libertarian. Those reports, and the absence of political matters on his phone or other communications, suggest that his motivation was something other than wanting to do away with a candidate who may or may not have infuriated him.

Still, the black hole that Crooks has created is being filled by Republicans, such as J.D. Vance, who eagerly blame Democrats and the media for demonizing Trump – an odd flip, since Democrats and the media are routinely demonized by such Republicans. It’s also being filled, to a degree, by Democrats, such as President Biden, who blame the hot rhetoric of the campaign for a toxic atmosphere, implying that such language drove Crooks to his mad actions.

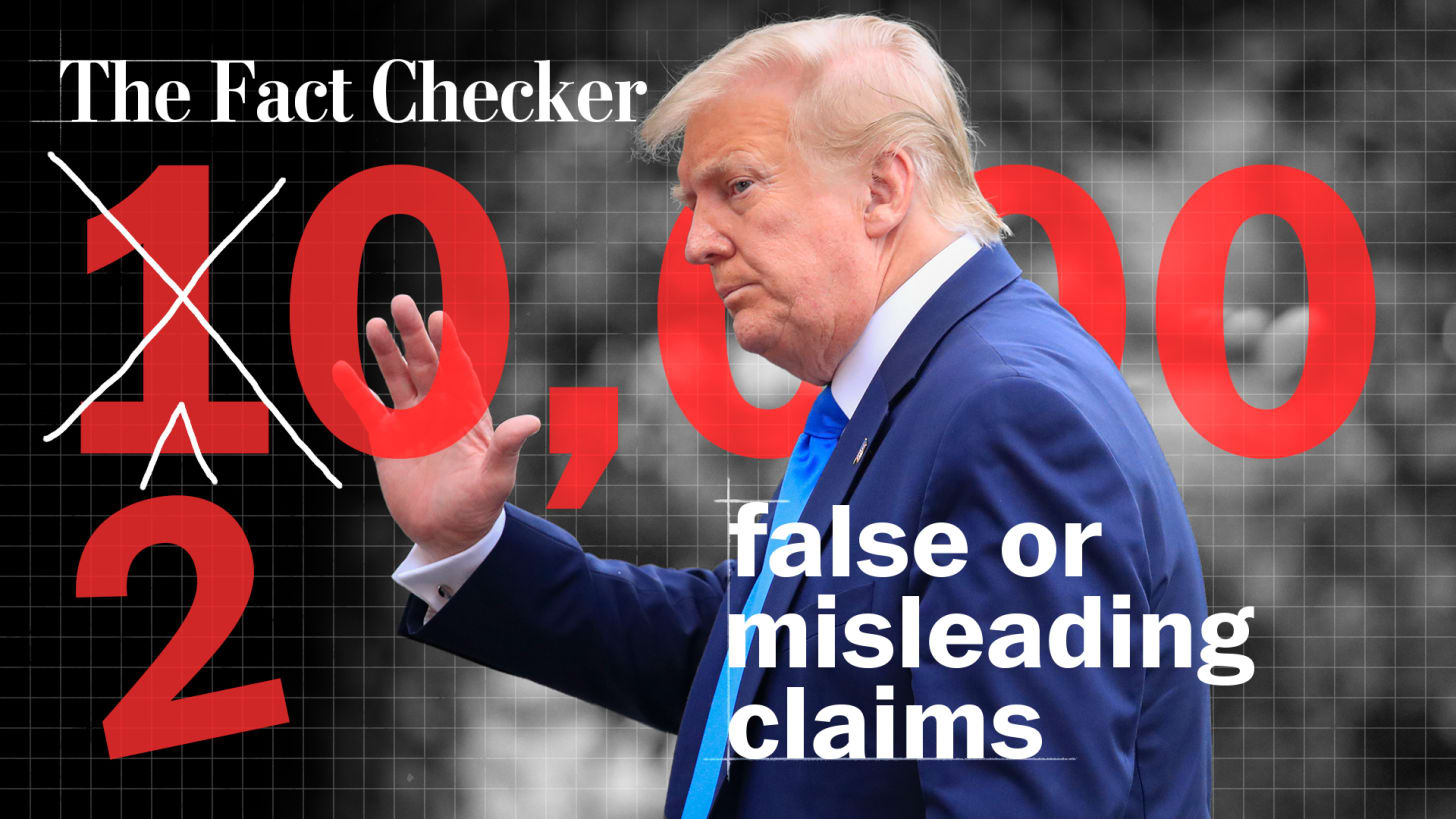

One of the more seemingly sophisticated commentaries was offered by author Gerald Posner, who rushed into print in The Wall Street Journal just two days after the July 13 shooting to blame “incendiary political language.” From whom? Well, liberals and the media, of course. “The assassination attempt against Mr. Trump follows years of relentless attacks from left-wing media and many in the Democratic Party, who likened the former president to Hitler and claimed his re-election would end democracy,” Posner argued.

Posner, a lawyer and an investigative journalist who wrote well-regarded books about the assassinations of JFK and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., compares the “volatile atmosphere” in Dallas in 1963 and in Memphis in 1968 with today’s environment, warning that “reckless speech” can inspire an assassin. He makes the link, even as he undercuts his argument by acknowledging that we may never know the motivations of Lee Harvey Oswald and James Earl Ray, as we may never know what drove Crooks.

This is a classic case of correlation versus causation: I got up and the sun came up this morning, so therefore I must have caused the sun to rise. Similarly, people said nasty things about Kennedy and King, therefore those comments must have caused their killings. Today, people are saying nasty things about Trump, so it follows that someone would try to kill him. A lawyer such as Posner, frankly, should know better.

The questions his reasoning begs are legion. Here are a few: did critical things that people said about Trump drive Crooks? Or might it have been Trump’s own many vile comments, some of which incited the riot in the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021? Or might both those things have been irrelevant to a troubled loner who perhaps was looking for a way to write himself into history and do away with himself at the same time? Might it have been that Trump was just the famous politician on hand?

We may learn more as the FBI continues its investigation into Crooks. Perhaps his parents, acquaintances and workmates will shed more light as time goes on.

But we also may never know, as Posner sensibly admits. And, given that void, should the opportunists rule the day? Should Democrats and Republicans stop criticizing one another?

Certainly, Republicans are not holding back. “America cannot afford four more years of a Weekend at Bernie’s presidency,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis said, referring to the ‘80s comedy in which two salesmen accidentally kill their boss and then pretend he is still alive. “Let’s be honest here. Biden is just a figurehead.”

And some argue that Democrats should not fall into a trap by backing off on warning Americans about the dangers of a second Trump presidency.

“Donald Trump really does present a threat to the norms of liberal democracy and the welfare of millions of US residents,” Vox commentator Eric Levitz writes. “Joe Biden truly supports the legality of medical procedures that some Christian conservatives believe to be murder. Rhetoric that describes in good faith our polity’s disputes will imply that our elections have life-or-death stakes — because they do.

“That Trump poses a threat to democracy should go without saying,” Levitz adds. “As president, he attempted to block the peaceful transfer of power by manipulating vote counts and instigating a riot on Capitol Hill. He has also outlined plans for undermining the independence of federal law enforcement while vowing to enact ‘retribution’ on his movement’s enemies.”

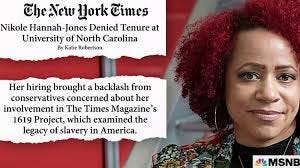

Those unaware of the profound effect a Trump presidency could have can turn to plenty of places for info. As The New York Times reported, and I’ve previously recounted, he would step up the trade war that already is riling global relations, imposing stiff tariffs that will drive up prices on broad ranges of goods for Americans. He would set up WWII-style detention camps to hold rounded-up migrants for mass deportations, try to end birthright citizenship, use the Justice Department to persecute his enemies, strip employment protections from tens of thousands of civil servants, purge intelligence agencies and other bodies of people whose work he dislikes, and he would cut taxes for wealthy friends, driving up the national debt anew.

Even more discomfiting things might come if Trump associates at The Heritage Foundation have their way. Their Project 2025 would reduce the size of federal agencies, ban abortion drugs, and overhaul popular programs like the Affordable Care Act, as a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel writer reported. He argued that it could cause immense harm to “women of childbearing age, undocumented immigrants, public education, diversity, equity and inclusion programs, unions, and the LGBTQ community.” Critics say Trump would enjoy “unprecedented and potentially dangerous powers unlike any occupant of the White House in American history.”

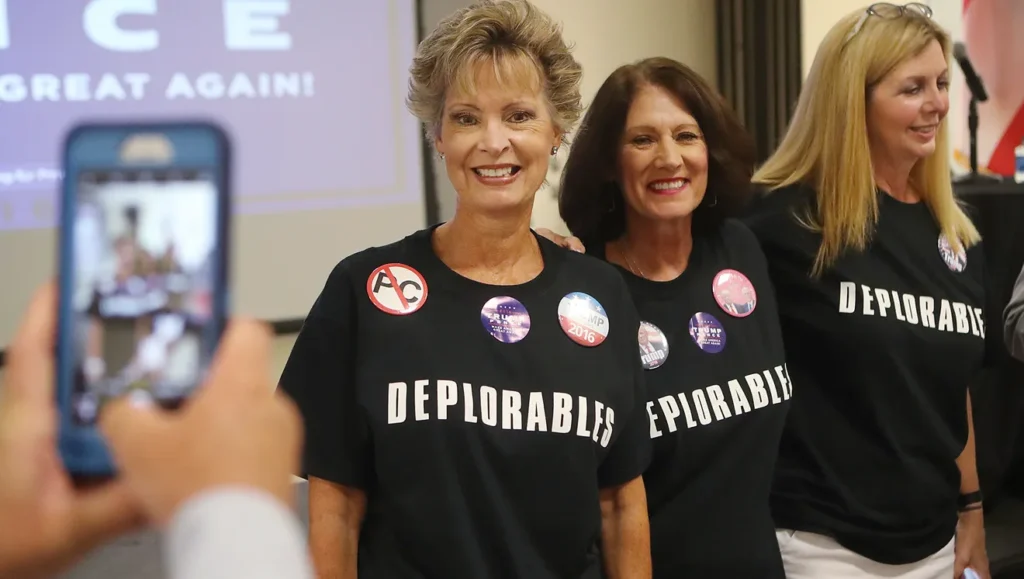

Certainly, there’s no dearth of information about what a Trump presidency would bring. The problem is that his supporters either back his agenda or don’t bother to inform themselves about it, as they remain under his demagogic sway.

Sadly, no amount of information may swing enough devotees away from Trump’s magnetic lure. And it remains to be seen whether Biden could be persuaded to yield the ground to a younger Democrat who could better go toe-to-toe with the former president.

Still, filling voids with misinformation seems to help only Trump. And, in this regard, jailed former Trump adviser Steve Bannon once offered some perverse wisdom: “The Democrats don’t matter,” Bannon told writer Michael Lewis in 2018. “The real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.”

The GOP and folks such as Posner are doing that to a fare-thee-well.