Can media outlets, such as The New York Times and NPR, maintain their credibility in the Trump era?e

Ah, the power of disinformation. It distorts the truth and, sometimes sullies the media that report it. Consider a couple matters that raise issues of bias:

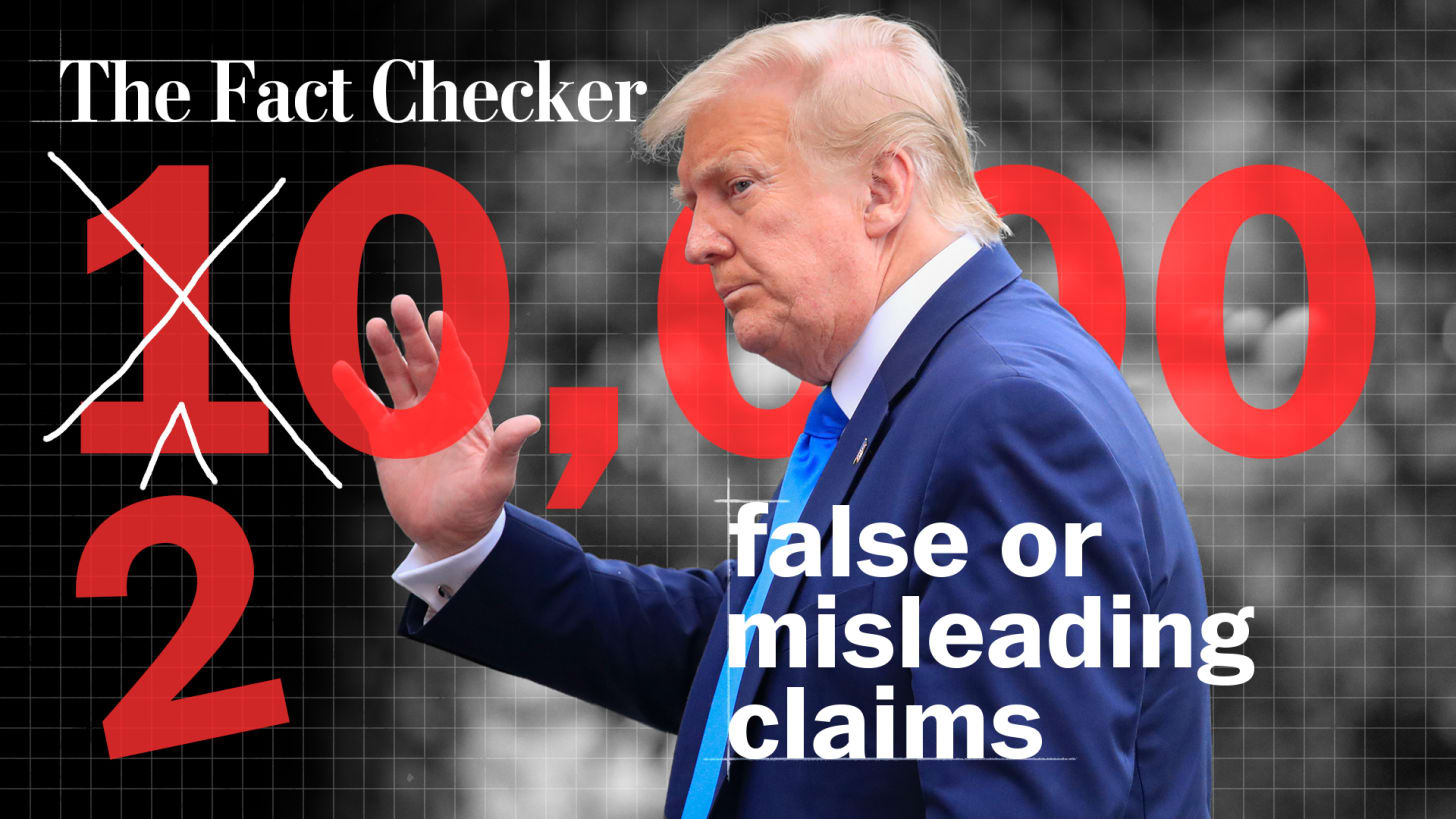

The New York Times, in the recently published “The Method Behind Trump’s Mistruths,” offers a rich catalog of the former president’s misstatements and distortions – all accompanied by real facts that undercut his claims.

To take a couple examples:

- “While Joe Biden is pushing the largest tax hike in American history – you know, he wants to quadruple your taxes.”

In fact, as the piece notes: “President Biden has not proposed quadrupling taxes. In fact, he has consistently vowed not to raise taxes on anyone earning less than $400,000.”

- “I mean, what he’s doing with energy with an all-electric mandate, where you won’t be able to buy any other form of car in a very short period of time.”

In fact, as noted, “Mr. Biden has not implemented an electric car mandate. The administration has announced rules that would limit tailpipe emissions from cars and light trucks, effectively requiring automakers to sell more electric vehicles and hybrids. It doesn’t ban gas cars.”

Such correctives – and those applied to more than a dozen more misstatements by the former president – are appropriate and helpful. The disgraceful roster of mistruths by Trump should be beneath anyone running for the presidency, much less a former president.

But the Times piece is not called “opinion” or, better, “analysis.” And yet the author offers a lot of both in framing his view of Trump in the opening paragraphs:

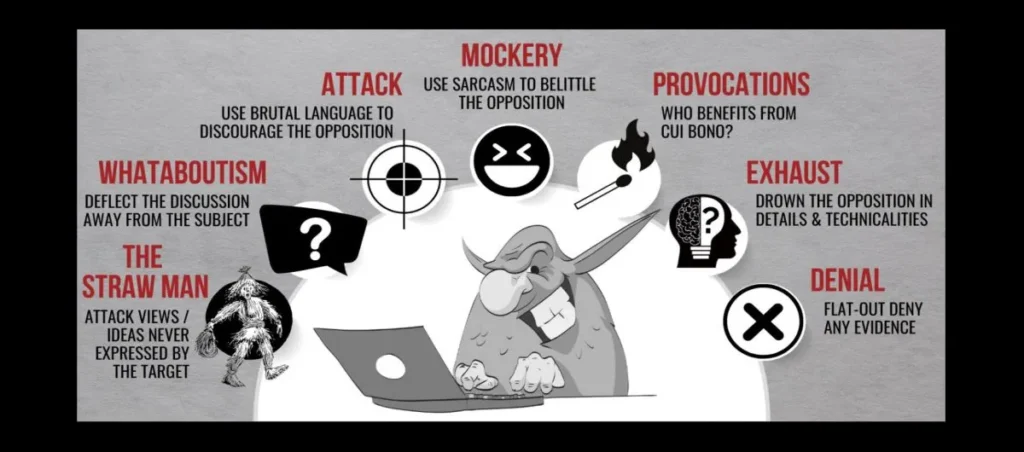

“Since the beginning of his political career, Donald J. Trump has misled, mischaracterized, dissembled, exaggerated and, at times, flatly lied. His flawed statements about the border, the economy, the coronavirus pandemic and the 2020 election have formed the bedrock of his 2024 campaign.

“Though his penchant for bending the truth, sometimes to the breaking point, has been well documented, a close study of how he does so reveals a kind of technique to his dishonesty: a set of recurring rhetorical moves with which Mr. Trump fuels his popularity among his supporters.”

None of that is untrue, though much is a matter of interpretation – “bedrock of his 2024 campaign” and “kind of technique to his dishonesty,” for instance. Moreover, there’s no attempt to balance any of this with comments from, say, Trump’s spokesman. The author doesn’t present “the other side” from a Trump defender, perhaps from someone who would rationalize away the former president’s claims as just hyperbolic.

Is it fair journalism, nonetheless? Is it a good-faith effort to combat disinformation of the sort that has marked Trump’s career for years, both as a real-estate mogul whose failures are legend and as a politician given to fabrication?

Indeed, would efforts to get another side be an example of “bothsidesism,” an approach that critics rightly say gives credence to falsehoods?

For my part, I see the Times piece as very much on target and factually devastating. But I suggest that labeling it as something other than straight news would be helpful. When such pieces go unlabeled, the media are dismissed by Trumpists as incurably biased.

Sadly, that gives credence to Trump’s attacks on the “fake news” media. Such attacks have driven many on the right, I suspect, to not pay attention to troubling stories about Trump’s business interests and his political plans.

Some turn, I suspect, to Fox News, Newsmax or similar outfits that don’t hold their golden boy to account for his untruths.

To be sure, the Times and others should carry opinionated material. But it’s not straight reporting and shouldn’t be portrayed as such.

Bias – or perceived bias — though, goes further than just labeling. Media outlets can betray their viewpoints both in the stories they choose to cover and those they avoid.

Troubling examples come in a scathing piece about National Public Radio in the conservative outlet, The Free Press. In it, longtime NPR staffer Uri Berliner bemoans the lack of “viewpoint diversity” in the outlet’s news operation. Because of its groupthink, Berliner suggests, stories are not being done that should be.

Criticizing NPR’s coverage (or lack of coverage) of the COVID-19 lab leak theory, Hunter Biden’s laptop, and allegations that Donald Trump colluded with Russia in the 2016 election, he contends that “politics were blotting out the curiosity and independence that ought to have been driving our work.”

To detail one example, NPR paid little mind to the Hunter Biden laptop story in the fall of 2020, even though, Berliner argues, “(i)ts contents revealed his connection to the corrupt world of multimillion-dollar influence peddling and its possible implications for his father. The laptop was newsworthy. But the timeless journalistic instinct of following a hot story lead was being squelched. During a meeting with colleagues, I listened as one of NPR’s best and most fair-minded journalists said it was good we weren’t following the laptop story because it could help Trump.”

The NPR veteran also lambasts the lack of conservative voices on staff, saying that “people at every level of NPR have comfortably coalesced around the progressive worldview.” He backs that up with a look at the Washington offices: “Concerned by the lack of viewpoint diversity, I looked at voter registration for our newsroom. In D.C., where NPR is headquartered and many of us live, I found 87 registered Democrats working in editorial positions and zero Republicans. None.”

That observation begs the question: can a Democrat fairly cover a Republican, and vice versa? I would argue yes, but it’s also helpful if one can find more stripes than one in a news organization. If nothing else, the lack of variety means one risks everyone moving in lockstep, in questions not being asked. Even the Times has bona fide conservatives writing for its opinion pages.

A lack of intellectual diversity, Berliner contends, shapes NPR’s work and is costing listenership. “An open-minded spirit no longer exists within NPR, and now, predictably, we don’t have an audience that reflects America.”

“Back in 2011, although NPR’s audience tilted a bit to the left, it still bore a resemblance to America at large,” Berliner writes. “Twenty-six percent of listeners described themselves as conservative, 23 percent as middle of the road, and 37 percent as liberal. By 2023, the picture was completely different: only 11 percent described themselves as very or somewhat conservative, 21 percent as middle of the road, and 67 percent of listeners said they were very or somewhat liberal.”

“We weren’t just losing conservatives; we were also losing moderates and traditional liberals,” Berliner argues.

Media outlets will lose their audiences if they don’t reflect them and speak to them in their journalistic work. That doesn’t mean pandering and certainly doesn’t mean reporting untruthfully or incompletely.

Finding the truth is a messy matter and giving charlatans platforms to spout unchallenged misstatements – as the right-leaning media often do – is not good journalism, of course. It’s the media’s job to hold officials and would-be officials to account, to call out their shortcomings and misstatements — but to do so in appropriate ways.

Later this year, I suspect we will see Trump and Biden square off in debates, at least if major news organizations get their way. And we can expect many misstatements to be aired, probably more from the former president than the current one. Will fact-checking help? Will partisans simply dismiss that? And can it be done in real-time, as the contenders rail against one another?

Politicians who shun facts have made a mockery of the most cherished journalistic tenets. Sadly, they could drag sound journalistic organizations down to their level, hurting all of us. The smartest outlets shouldn’t fall for that.