A deeper look at the Israel-Hamas war protests

As we all know, many colleges erupted in protests and counterprotests following the October 7th atrocities in Israel. Some universities in areas with substantial populations of Jews and Arabs, particularly Palestinians, slipped into violence from scuffles, thankfully minor in most cases. Members of both groups raised alarms about fearing to walk on the campuses or even attend classes because of the tensions and some people even sued about it.

While most schools seem to have settled down, as the war goes on and the new term wears on, it’s reasonable to expect still more unrest. Pro-Palestinian student groups, including reorganized unofficial ones that replaced those banned at some schools, were disrupting classes at Harvard as recently as last month. At best, we can hope the tactics of such groups remain peaceful.

As I’ve prepared for a Jan. 24 presentation about the campus reactions for the Federation of Jewish Men’s Clubs, I’ve been struck by a few key points about these protests. Let me share a few:

First, it is stunning that the pro-Palestine students refuse to condemn Hamas, both for the vile attacks of October and for the group’s heartless approach to the innocents of Gaza. Even women have turned a blind eye to the savagery targeting Jewish women. Hamas knew, of course, that it was inviting the retaliation it has gotten, seemingly unconcerned and willing to treat its own people as welcome cannon fodder.

Instead of protesting against the terrorists, the demonstrators seem to either ignore their monstrous actions and their perversions of Islam or to celebrate them. It’s one thing to stand up for one’s people — the innocents in Gaza caught in the crossfire — but it’s another to misplace the blame. It’s as if the demonstrators’ moral calculations are upside down. And we see absurdities such as LGBTQ community members defending Hamas, a group that would toss them from the highest buildings if they lived among them.

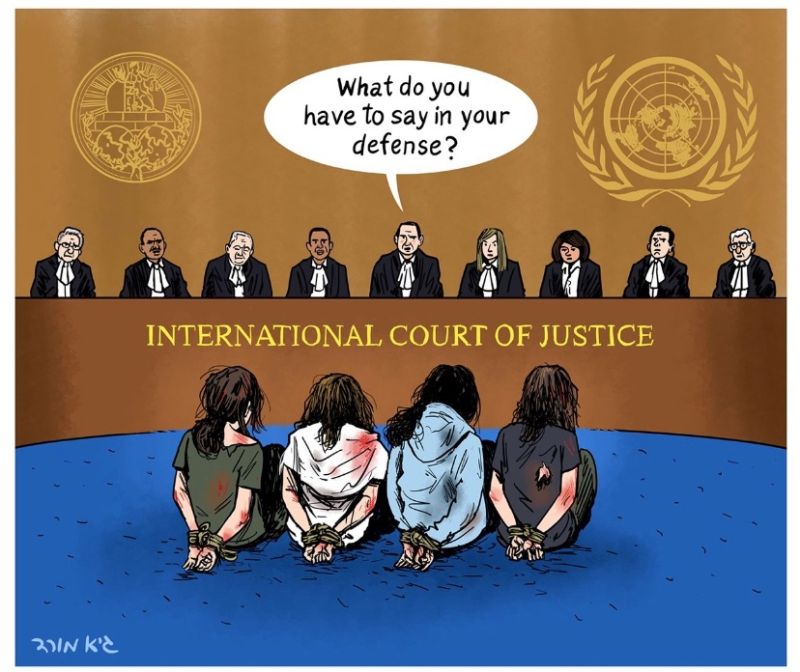

The moral inversion of these protestors is just as perverse as South Africa’s claim that Israel is guilty of genocide and its backwards arguments before the International Court of Justice. To argue that a nation defending itself against terrorism is intending to wipe out a couple million people even as the terrorists continue to hold that nation’s citizens hostage is obscene — especially when that nation, Israel, has repeatedly warned Gazans to leave Hamas-infested areas. Why is Hamas not on trial instead for its barbarism?

Second, I’m struck by how widespread the ignorance about the complex history of Israel-Palestine relations is, particularly among young people. When they chant “from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free,” many don’t seem to realize that is a call for the eradication of Israel, that it is the ultimate in antisemitism. As a recent column in The Wall Street Journal noted, many of the students chanting this nowadays don’t even know what river or sea are being referred to.

In addition, ignorance about the Holocaust is extraordinary only 80 years after that monstrosity. One-fifth of U.S. citizens between the ages of 18 and 29 believe that the Holocaust is a myth, according to a poll by Economist/YouGov.

And, as the Israeli military has grown into one of the most powerful forces in the region, there’s also a peculiar underdog sympathy taking hold – one that affects Jews worldwide, not just in Israel. A Harvard-Harris poll in December reported that 44 percent of Americans ages 25 to 34, and a whopping 67 percent of those ages 18 to 24, agreed with the statement that “Jews as a class are oppressors.” By contrast, only 9 percent of Americans over 65 felt that way. This is concomitant with a rise in antisemitic incidents, including over 500 on campuses since early October.

On the positive side, some schools have seen a surge in interest in courses dealing with the Middle East. Among these are Bard College, the University of Washington, and the University of Maryland. Even at Harvard, Derek Penslar, a professor of Jewish History, has seen substantial demand for a course he teaches, for instance. “The students who walk in my door are not necessarily the same ones as those who are in Harvard Yard screaming,” he told Inside Higher Ed. “More often than not, my students are curious, intelligent, and they usually do have a political view at one point or another. But they’re open-minded or else they wouldn’t bother taking my class.”

Third and finally, the problems on campuses are both short-term and long-term. In the coming few months, the challenges will be to allow for free speech — an essential part of a university experience — but also to assure student safety. Both Arab and Jewish students need to be able to feel physically safe and comfortable enough to have civil conversations inside and outside class. The war is ugly enough without bringing its effects here.

Longer-term, the challenge is for universities to teach more students — especially those most in need of knowledge — about the complexities of the Middle East and about the ugliness of antisemitism. One approach is to improve diversity, equity and inclusion programs to include mandatory sessions about Jewish and Arab history, much as they do now about Blacks and whites. After all, what is higher education about, if not education?

We’ll have a chance to look in depth at these issues in the upcoming FJMC webinar. It’s likely that this will be a sobering look, but an informative one, I hope.