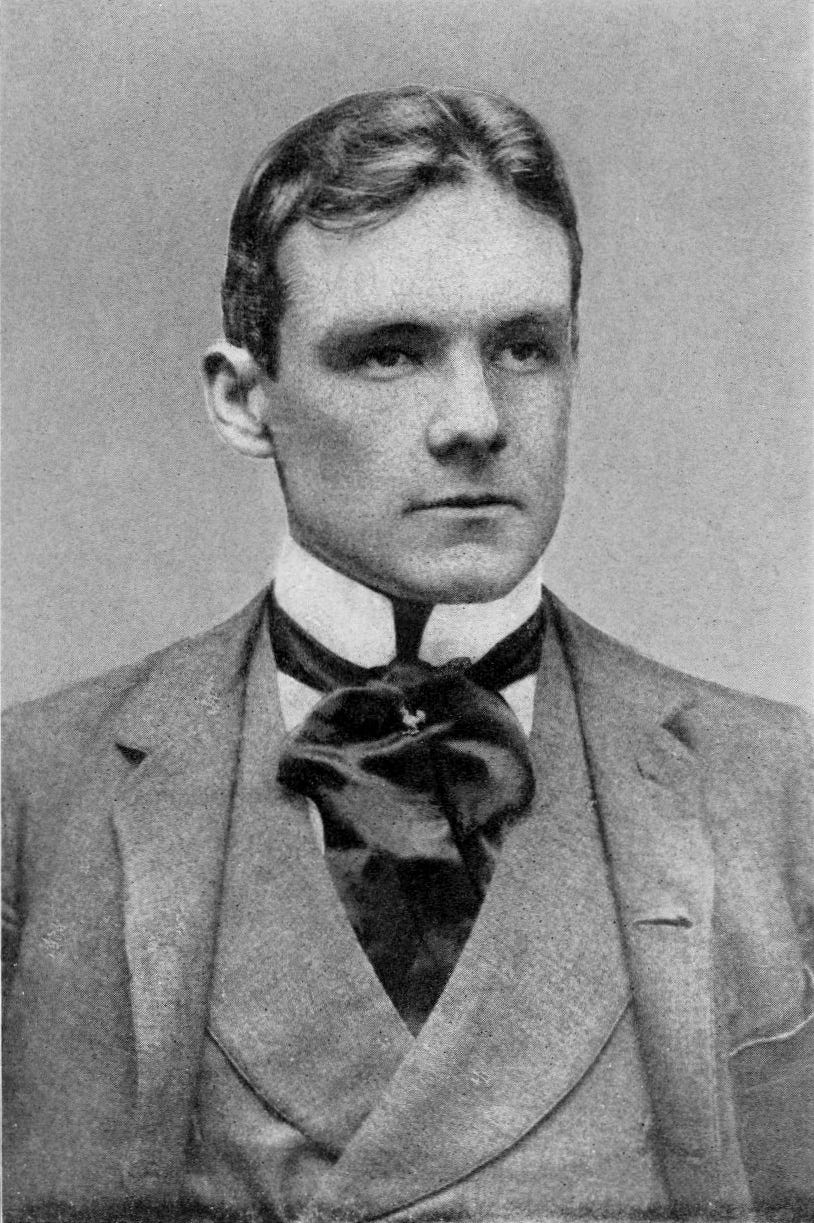

As I walked my dog down 21st Street in Center City Philadelphia the other night, a plaque on an otherwise undistinguished townhouse grabbed my eye. The place, it said, was the boyhood home of Richard Harding Davis, an exceptional fin de siecle author and journalist whose work would humble most modern reporters.

Davis covered six wars, including the Spanish-American War, the Boer War and World War I. Strains from his war correspondence may have contributed to a heart attack that killed him just shy of age 52, , according to the report of his death in 1916 in The New York Times, His adventures got him arrested a few times as he ventured to the British and French fronts, even though he backed the Allies.

By today’s standards, Davis would hardly be called an objective observer. His forte was Yellow Journalism, the sort that provoked anti-Spanish sentiments in the U.S., particularly with reporting about Cuba. Apparently happy with his sympathetic coverage, Col. Teddy Roosevelt regarded Davis as a close friend and had made him an honorary member of the Rough Riders, the regiment Roosevelt led in the Cuban campaign. Before his adventures covering various wars, in one of his earliest reporting jobs, Davis put on what the Times called “rough clothing” to gain the confidence of burglars in a saloon, proving to be instrumental in the arrests of several of them.

Much of the journalism of his day was opinionated and its practices would never fly today. And Davis also ventured into areas where opinion and points of view were the explicit stock-in-trade. He served as managing editor of Harper’s Weekly in the mid-1890s, for instance. Moving beyond fact-based work, he also wrote a bevy of books and plays, including a long list of pieces that were turned into movies.

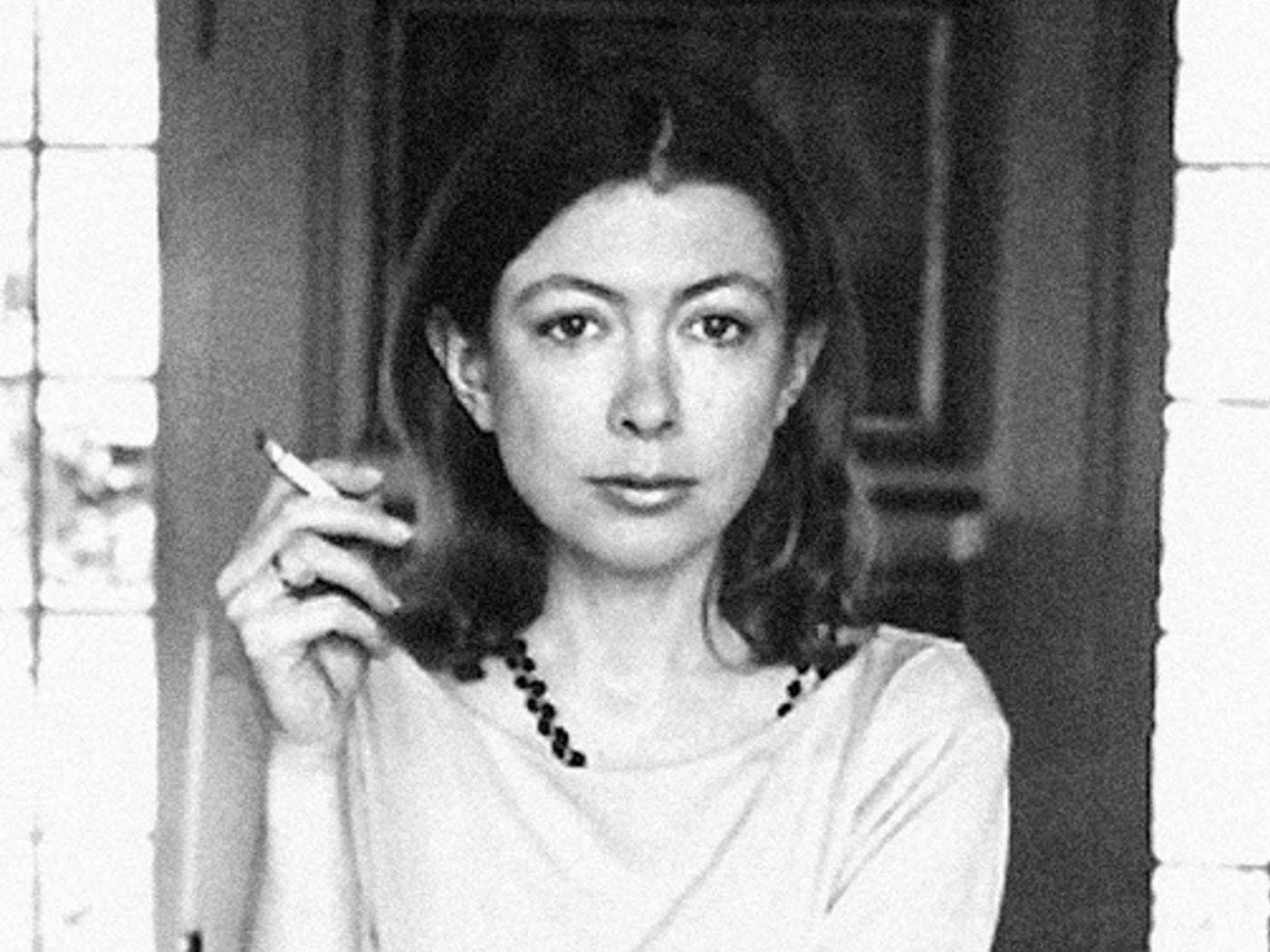

Over the decades since, plenty of reporters have turned their hands to books, of course, including both fiction and nonfiction. Ernest Hemingway’s early days in newspapering shaped his later writing (coincidentally Hemingway developed an affection for Cuba, much as Davis did decades before). More recently, so-called New Journalism practitioners such as Joan Didion blended fiction and nonfiction to write revealingly about American culture. The New York Times recently shed light on some of Didion’s experiences and views in the polarized 1960s.

And former journalists, such as David Simon of The Wire fame, have used the skills they developed in newspapers to enormous advantage. TV has benefitted richly from him and his likes.

Journalists who hew more closely to observable facts (and accounts by insiders involved in events) include such names as Bob Woodward, whose non-newspaper work may not equal Davis’ output in volume but certainly does in impact. Others of this sort are Jane Mayer, John Carreyrou and Janet Malcolm. Many such folks have worked for outlets of varying sorts. New York Times senior writer David Leonhardt, for instance, won awards at BusinessWeek before going on to win a Pulitzer Prize at the Times. So far, he has authored two books, including a fresh take on the American economy.

Despite the prominence today of such star journalists and former journalists, one wonders about the future. Will it include more of the distinguished work of the sort they’ve done or less; more such star writers or fewer? They forged their skills in news outlets now under siege by economics, the rise of social media, cable TV and distractions of all sorts. Where will tomorrow’s writers hone their skills?

It’s hard to be optimistic at a time of such ferment in media. Certainly, the output of today’s stars is impressive. And, no doubt, some of the stars of tomorrow are toiling away now in news operations that hang on all across the country. But how long we will get to enjoy them, and how brightly they will shine in coming years, is anyone’s guess.

Decades hence, plaques may be placed on the childhood homes of some of today’s stars. Will folks walking by such places have journalists then working, using similar talents, to think about?