Thanks to the Prime Minister of England, Simon Warner and I met 33 years ago. Now, because of that PM’s death and the marvels of the Net, we’ve met again – electronically at least. And in that lay an intriguing tale of media, globalization and winding career paths.

Thanks to the Prime Minister of England, Simon Warner and I met 33 years ago. Now, because of that PM’s death and the marvels of the Net, we’ve met again – electronically at least. And in that lay an intriguing tale of media, globalization and winding career paths.

Credit Margaret Thatcher first of all. The feisty Conservative lioness, derided or admired as “the Iron Lady,” was running the U.K. when I was lucky enough in 1980 to be chosen for a journalism exchange program created by the English-Speaking Union. Chartered by the Queen, the E-SU promotes friendship among English-speaking peoples and had enough clout to get me into 10 Downing St. to sit with the PM for a while.

Imagine what a thrill this was for a 25-year-old reporter for a little New Jersey paper, The Home News. Mostly, I wrote about small-town mayors and the occasional county official. Now, I would get to interview a sitting PM, one who cut a swath culturally and politically almost as big as that of her buddy, Ronald Reagan. Some loved her, many hated her and I’d get to write about her.

The ways of politicians can be mysterious, of course, so things didn’t turn out quite as I expected.

Simon, right in the photo above, was the first surprise. Someone decided a young American reporter should be paired with a young British reporter for a sit-down with Mrs. Thatcher. That was no problem, of course. We met at 10 Downing St. on the big day, July 14, equally excited about our big interview. Back then, exclusivity wouldn’t matter much, since we worked on different continents.

But then, as we waited in an anteroom, the PM’s PR man delivered the bad news. The London media were in high dudgeon about a couple young journos – one an American! – getting access to Thatcher when she had no time for them. Some reporter even wrote a snarky piece about it (long before anyone heard the word snarky). So, the conversation would have to be off the record. No notebooks, no tape recorders, no interview story.

Weeks of boning up went out the window, but, okay, we’d meet anyway. And we did. We had a fine time, talking mostly about innocuous things, such as her son’s adventures around the world. Mostly, Simon and I listened, unable to get a word in edgewise with the imposing Mrs. Thatcher (not that she needed us to, of course). Simon’s editors, with the help of a local Member of Parliament, later negotiated the chance for him to write about the conversation a bit for his paper, The Chester Observer. I got a piece for my paper out of the visit, but just shared my impressions of the PM and spelled out her successes, failures and fights in office. Happily, we could run the photo of the meeting.

Weeks of boning up went out the window, but, okay, we’d meet anyway. And we did. We had a fine time, talking mostly about innocuous things, such as her son’s adventures around the world. Mostly, Simon and I listened, unable to get a word in edgewise with the imposing Mrs. Thatcher (not that she needed us to, of course). Simon’s editors, with the help of a local Member of Parliament, later negotiated the chance for him to write about the conversation a bit for his paper, The Chester Observer. I got a piece for my paper out of the visit, but just shared my impressions of the PM and spelled out her successes, failures and fights in office. Happily, we could run the photo of the meeting.

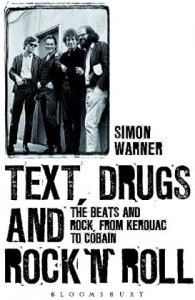

Fast forward to this past week. Touched by Mrs. Thatcher’s death, I tracked down Simon, with just a few clicks on Google (smiling in the head shot to the right here today). He rose through the ranks in journalism, becoming arts editor at a couple regional papers in the 1980s, did media relations in arts and education, and became a live rock reviewer for The Guardian during the 1990s. He earned a master’s in popular music studies, then a Ph.D., and now serves as a Lecturer at Leeds University. He’s a prolific writer, with at least five books about major cultural figures dear to Boomers. These include “Rockspeak: The Language of Rock and Pop,” “Howl for Now: A celebration of Allen Ginsberg’s epic protest poem,” “The Beatles and the Summer of Love,” “New York, New Wave: From Max’s and the Mercer to CBGBs and the Mudd Club,” and his latest, the just-issued “Text and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll: The Beats and Rock Culture.”

The similarities in our career paths intrigue me. We both wound up working for national pubs and both wound up leaving workaday journalism for the academy. Though I spent my career mostly in business news, we also both have written about popular culture and figures important to fellow Boomers (my book about the legacy of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Beatles guru, and his followers’ community in Fairfield, Iowa, is due out early next year). We’re both fans of the Beats (though I mostly left them behind in high school, while Simon has dug deeply into those folks and the long shadow they’ve cast. Gotta love the photo on his latest book cover).

The similarities in our career paths intrigue me. We both wound up working for national pubs and both wound up leaving workaday journalism for the academy. Though I spent my career mostly in business news, we also both have written about popular culture and figures important to fellow Boomers (my book about the legacy of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Beatles guru, and his followers’ community in Fairfield, Iowa, is due out early next year). We’re both fans of the Beats (though I mostly left them behind in high school, while Simon has dug deeply into those folks and the long shadow they’ve cast. Gotta love the photo on his latest book cover).

Nowadays, we both also wonder about the future of journalism. Simon emailed me about it: “The media business remains close to my heart but how can print survive? Transatlantically, the great newspaper empires are caught on the horns of a dilemma. Can paywalls work? Can Internet advertising eventually bridge the losses to income that traditional papers, with their shrinking readerships, are suffering? The Guardian, to which I contributed for several years, is attempting to raise its US profile but can that bring dividends? Meanwhile, the middle-market Daily Mail is proving a web hit, of course, overtaking the NYT in terms of visitors!”

Also like me, Simon blogs. He wrote about his media adventures in 2009 in his “Words of Warner.” Interesting read.

So, we’ve enjoyed somewhat parallel lives on different sides of the Atlantic. Their arcs don’t quite reflect that of Lady Thatcher, who lived on a far grander stage, of course. But, at a nice point for all of us, our paths crossed. And now, thanks to the same technology that is upending the media, Simon and I get to say hello again. I plan to buy his latest book, snapping it up as an ebook I can read on my iPad. Small and surprising world, isn’t it?