Anti-intellectualism has a long history in American culture

A friend set me to thinking about the long and unsavory history of anti-intellectualism in American life. This strand of our culture didn’t begin with Trumpism, of course, though the anti-science and anti-elites chords the former president strikes so powerfully are exceptional examples of it. Indeed, it’s not by accident that Donald Trump in 2016 singled out the group he had most affection for, saying: “We won with young. We won with old. We won with highly educated. We won with the poorly educated. I love the poorly educated.”

Nor has this phenomenon been exclusively a province of the right, which boasts of many ignorant folks but also the likes of the brilliant (if often distasteful) William F. Buckley. In fact, a most intriguing commentary on the phenomenon came in 2001 from conservative economist Thomas Sowell in “The Quest for Cosmic Justice,” where he wrote:

“From its colonial beginnings, American society was a ‘decapitated’ society—largely lacking the top-most social layers of European society. The highest elites and the titled aristocracies had little reason to risk their lives crossing the Atlantic, and then face the perils of pioneering. Most of the white population of colonial America arrived as indentured servants and the black population as slaves. Later waves of immigrants were disproportionately peasants and proletarians, even when they came from Western Europe … The rise of American society to pre-eminence, as an economic, political, and military power, was thus the triumph of the common man, and a slap across the face to the presumptions of the arrogant, whether an elite of blood or books.”

As a trip through Wikipedia reveals, there is much support for Sowell’s view. A minister in 1843 wrote about frontier Indiana (one of our most undereducated states): “We always preferred an ignorant, bad man to a talented one, and, hence, attempts were usually made to ruin the moral character of a smart candidate; since, unhappily, smartness and wickedness were supposed to be generally coupled, and [like-wise] incompetence and goodness.”

Such views have long infused our politics, sometimes with well-schooled leaders who either demagogued on this stream of thought or just warmed to it. Consider the 1912 thoughts of Woodrow Wilson, who, despite his doctorate from Johns Hopkins, said: “What I fear is a government of experts. God forbid that, in a democratic country, we should resign the task and give the government over to experts. What are we for if we are to be scientifically taken care of by a small number of gentlemen who are the only men who understand the job?”

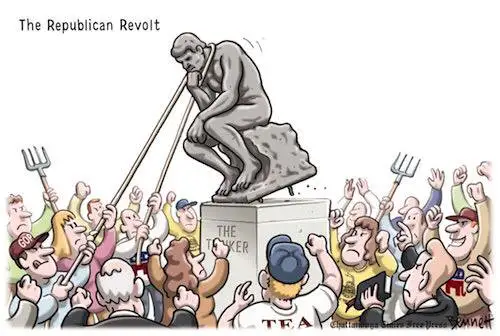

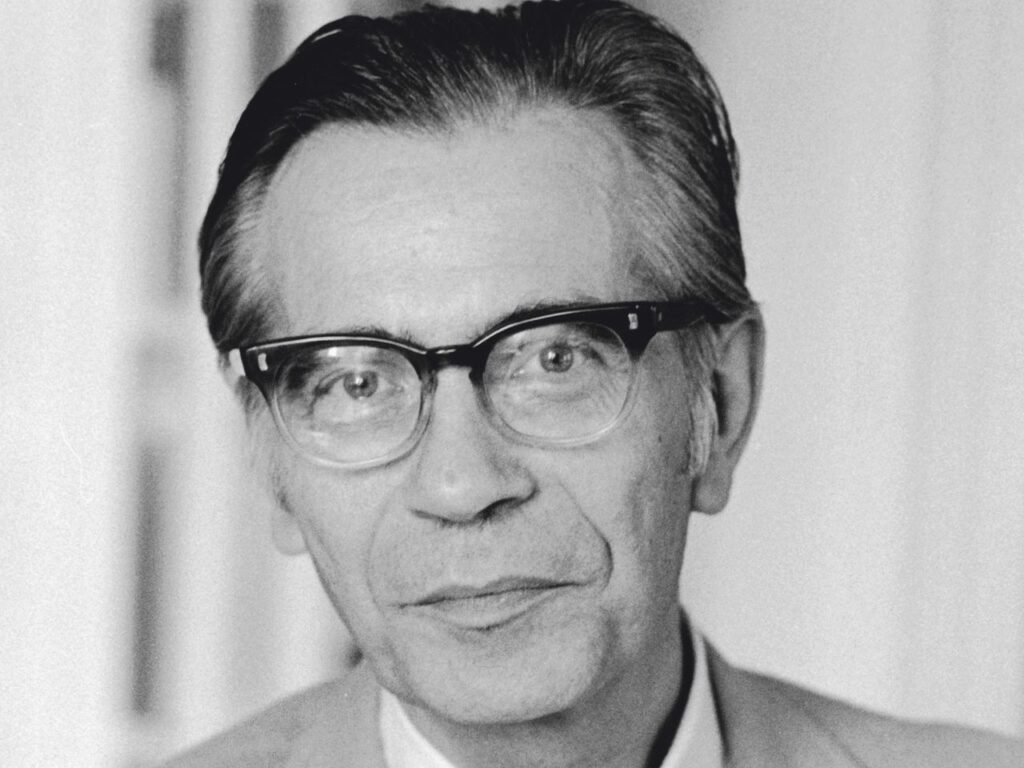

A thorough discussion of this trend came in 1963 from Columbia historian Richard Hofstadter. In “Anti-intellectualism in American Life” he argued that anti-intellectualism was how the middle-class showed its feelings for political elites. As that group developed political power, he contended, it held up the ideal candidate for office as the self-made man, not a well-educated man born to wealth.

More recently, in 1980, author Isaac Asimov observed: “There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there has always been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge’.”

Since then, many folks have dusted off this theme. Journalist and author Susan Jacoby in her 2008 book, “The Age of American Unreason,” bemoaned what she called the resurgence of anti-intellectualism in the modern era. According to The New York Times, she blamed it on television, video games and the Internet, saying they created a “culture of distraction” that has shortened attention spans and left people with “less time and desire” for “two human activities critical to a fruitful and demanding intellectual life: reading and conversation.”

Certainly, the forces Jacoby pointed to exacerbate the cult of ignorance we are awash in. Still, history shows that it’s nothing new. The new media that preoccupy us now may just be building on that well-rooted base. One has only to look at the success of Fox News to see how deep that base is.

We might take heart, however, that there’s an ebb and flow at work. At various times in our history, we have swung from respecting (and electing) smart people to choosing ignoramuses. How else to explain descents such as that from Thomas Jefferson to Andrew Jackson (in just 20 years) and from Barack Obama to Donald Trump (in no time at all)?

It’s troubling, nonetheless, that politicians such as Ron DeSantis feel a need to play down or deride their elite-education credentials to try to harness votes from the masses that are less-schooled than they. After using Yale as a steppingstone to Harvard Law School and then entering politics, he soon realized that such credentials were “a political scarlet letter as far as a G.O.P. primary went,” as The New York Times reported. As he has sought to remake higher education in Florida, DeSantis has also said he would eliminate the federal Department of Education, among other agencies.

For his part, Trump has bragged — when it suited his purposes — about attending an Ivy League school, the University of Pennsylvania, even as he failed to mention that he had transferred there after two years at the less tony Fordham University, as The Daily Pennsylvanian reported. In fact, he claimed to have graduated first in his class in 1968 at the university’s Wharton School, though the school newspaper’s investigation of this did not bear that claim out. Indeed, he did not even make dean’s list that year.

He also has often derided intellectuals and pursuits such as reading. He told a reporter for The Washington Post in 2016 that he has never had to read very much because he can reach right decisions “with very little knowledge other than the knowledge I [already] had, plus the words ‘common sense.’ ” Moreover, Trump told the Post that he is skeptical of experts because “they can’t see the forest for the trees.”

Despite the choice of Joseph Biden in 2020, we seem now still to be perilously in a period when the pendulum remains far from valuing education in our leaders or elsewhere. Indeed, it’s troubling how few Americans today put a premium on schooling, a trend concomitant with the rise of book-banning nationwide. Our next election will be revealing about many things (not least of which are understandable concerns about the current president’s age), but it may also mark either a departure from the pendulum’s swing or its confirmation.