As we walked to lunch with faculty and a couple administrators the other day, we passed demonstrators holding a sit-in outside the Tsinghua administrative offices. Their placards told of how they wanted more money for the destruction of their homes, which was planned to make way for faculty housing. Our hosts, chagrined by the protest, nonetheless noted that this was an example of free speech. These people, it seemed, had a right to make their grievances known.

As we walked to lunch with faculty and a couple administrators the other day, we passed demonstrators holding a sit-in outside the Tsinghua administrative offices. Their placards told of how they wanted more money for the destruction of their homes, which was planned to make way for faculty housing. Our hosts, chagrined by the protest, nonetheless noted that this was an example of free speech. These people, it seemed, had a right to make their grievances known.

It seemed a lot like home. But, then at lunch, we got some friendly advice from a Party official who is a fellow academic. Be mindful of what we say in class, we were counseled. Chinese students, especially those from the countryside, give teachers enormous deference in this Confucian society. Moreover, with social media alive and well in China – through local knockoffs of Facebook and Twitter – anything we say may find an audience well beyond the classroom. Privately, say what you want. Publicly, be discreet. There’s a difference in China between the private and public realms.

We’re not in Kansas anymore, Toto. But, what a perplexing country this is. On the one hand, it has embraced so much about the West. Just look at the soaring skylines in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. And consider the recurring 10 percent-plus annual growth rates that put the U.S. and the rest of the economically turbulent West to shame. The Chinese are setting the pace for the world.

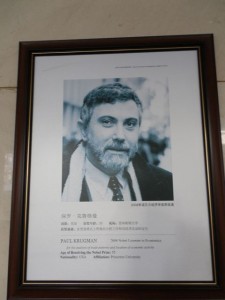

Their passion for capitalism is obvious. The school of economics and management here is a towering modern compound fronting on the strip of stunning buildings that adorn a stretch near the main gate. Inside one of the several buildings, portraits of Nobel Prize-winning economists make a long line in the lobby – seemingly, all are Americans, including New York Times columnist and Princeton economist Paul Krugman. By contrast, the university’s school of Marxism is tucked off in a less impressive quarter of campus, housed in a small, older building. I’ve heard Marxism is regarded as a matter of philosophy, nothing quite so practical as economics and management. Certainly, there’s no doubt who these folks want their students to look up to.Merit is also prized here, whether in school or in government. To join the Communist Party, our colleague explained, one must be in the top of one’s class academically. The Party is for the elite, those who can lead the country, and getting through the application process is tough and time-consuming. Only about six percent of the 1.3 billion people in the country qualify for Party membership (a surprising share, even if that amounts to 80 million folks).

Indeed, the Party leadership is composed of practical men with impressive academic backgrounds. Some have graduated from Tsinghua, with degrees in subjects such as water engineering. The current president, Hu Jintao, is an alum. The children of some of these men now study at Western institutions such as Harvard. These are bright people who, it seems, take seriously the need to intelligently manage a country where vast numbers still live in poverty a world apart from privileged city-dwellers. They seem to want to spread the wealth and manage the growth of their country well.

Indeed, the Party leadership is composed of practical men with impressive academic backgrounds. Some have graduated from Tsinghua, with degrees in subjects such as water engineering. The current president, Hu Jintao, is an alum. The children of some of these men now study at Western institutions such as Harvard. These are bright people who, it seems, take seriously the need to intelligently manage a country where vast numbers still live in poverty a world apart from privileged city-dwellers. They seem to want to spread the wealth and manage the growth of their country well.

And yet, there is a limit to how far western approaches go here. I bumped up against it the other day, when I wanted to shoot some photos at a central athletic field on campus. Large numbers of students paraded about the sprawling field in military uniforms. Military training, a student here told me, is required of all freshmen. Indeed, days earlier I saw similar troops of students marching around campus and singing songs of loyalty to the nation. It was reminiscent of years ago in the U.S., when students had to go through ROTC training on many campuses.

Struck me as interesting. But a fellow in a black athletic outfit thought otherwise. “Delete,” he told me politely — but firmly — as he appeared out of nowhere. This was arguably a public place, and certainly would have been considered so in the U.S. Further, he was not in uniform and didn’t say who he was. But I was in no position to argue. I am, after all, a guest in this country and must behave as one. I certainly don’t wish to offend my hosts, whose graciousness has gone above and beyond.

Odd thing is, other military events on campus seem to be fair game. For instance, I was able days before to photograph a flag-raising ceremony conducted by young people in front of the main administration building. Chinese people were similarly taking photos. That, it seemed, was acceptable even as the larger parade was not.So, every once in a while, I expect I’ll run into reminders that the rules are different here. As long as I am a guest, I will comply. Anything else would be ungracious, to say the least.