But just what is the megastar’s appeal?

Improbable as it may seem, our six-year-old grandson turned me on to Taylor Swift. First, I watched her Eras Tour film a week or so ago in his living room, and then I watched him on a couple long plane rides to and from Europe as he mimicked some of Swift’s moves, screening the film on his tablet at least five more times. As she pointed around the SoFi Stadium to her fans, he did the same from his airline seat.

Frankly, however, I couldn’t see Swift’s appeal. Similarly, it has been difficult for me to see the attraction Swift had for his 40-year-old mom, a draw strong enough to get her to pay a couple hundred dollars and bike quite a ways to one of the singer’s shows last July (a lucky bargain when some folks have paid as much as $18,000). I’ve also been challenged to see the allure for my 37-year-old son, who plans to take his six-year-old daughter from Germany, where they live, to a Swift show in Paris.

In the film, some of her appeal is the stunning staging on her tour. As she rises on a moving cube above the stage at times and struts along on top of and in front of dazzling lighting effects, the technology and choreography is captivating. It’s far superior to the most impressive concerts I went to decades ago. Her patter and warmth with her audience, too, is both gracious and intimate. Give her this, Swift is an extraordinary showwoman.

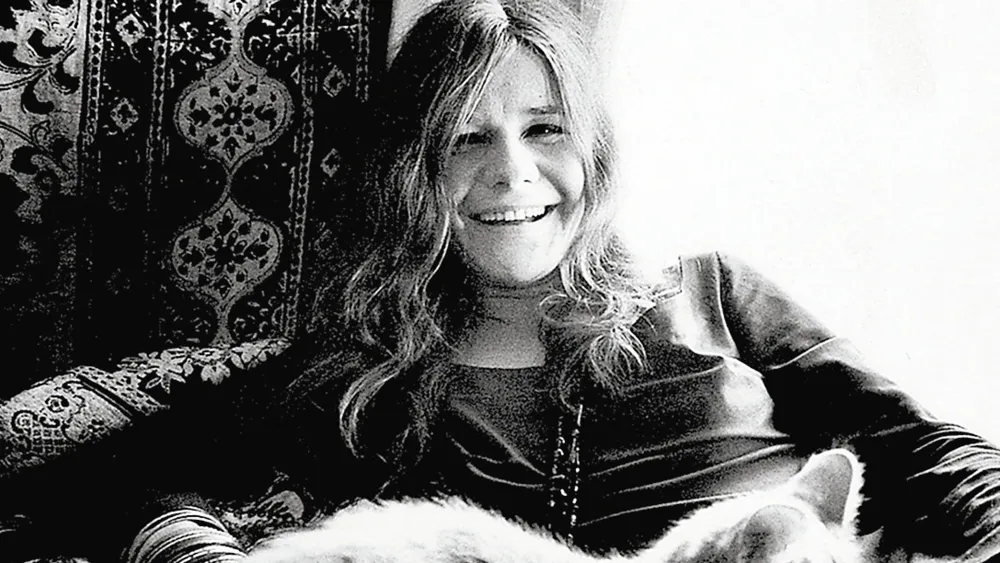

Her music, however, struck me at first blush as workmanlike, but bland – nothing like the pyrotechnics of the Stones or the Moody Blues, the ingenious and inventive sounds of The Doors and the Beatles, the thrilling power of Springsteen, or the passion of Janis. And on stage her lyrics seemed rushed, barely giving a listener a chance to let their meaning sink in, as seemed far easier with such brilliant lyricists as Dylan, Joan Baez, Paul Simon, James Taylor, Don McLean, Neil Young and others.

Still, there’s no denying that Swift has eclipsed all those setting stars. Her billion-dollar tour is a global phenomenon, lifting some national economies. Her romance with Travis Kelce has been a cultural touchstone. And should she again side publicly with Joe Biden against Trump (as she did in 2020), she could have a potent political impact (one that Springsteen was unable to have with Clinton against Trump). There’s no question that Swift deserved to be Time’s Person of the Year last year.

Indeed, even before my grandson’s fascination with her, I have wanted to understand the magic that is Taylor Swift, the passion that Swifties feel. Was it like the depth of feeling I once had for my rock and folk icons, musicians whose songs spoke to my deepest yearnings, my joys and sorrows, my hopes and fears, even to my sense of justice and injustice? Does her music speak to the angst of teens everywhere, as my aging heroes once did for me?

A recent podcast from The New York Times, provided by my son-in-law, went far to help develop my understanding. Journalist Taffy Brodesser-Akner refers in the pod to Swiftmania as “the cultural event of my lifetime.” As a 48-year-old, the writer said, “I remember the way my parents used to talk about Woodstock … And I began to see, first, that it was going to be Woodstock, and then it was going to be bigger than Woodstock. Then it was going to be something, like everything else about her, that we don’t have words to compare to. And that is what Taylor Swift is.”

Well, that’s quite a description, of course. But the author backs that up. For instance, when concertgoers in Seattle responded to Swift’s “Shake It Off” song, seismologists measured the stadium’s movements as equivalent to a 2.3 magnitude earthquake (it’s a wonder the Lumen Field venue didn’t collapse). Beatlemania pales by comparison.

The author, who also wrote about Swift for The New York Times Magazine, seemed to be onto something (at least for me) when she noted that listeners may not get what Swift is about during the first time listening to her lyrics, or even the second or tenth listening. Eventually, though, they realize that Swift is a “songwriting savant,” says Brodesser-Akner, and that the singer is “is telling the story of girlhood into womanhood…. I see her in real time cataloging the experiences of what it means to grow up.”

Bad romances, business and personal betrayals, self-doubt and even self-loathing fill Swift’s lyrics, Brodesser-Akner points out. And that is why so many fans, particularly women, respond. Swift speaks to their experiences, as if she’s holding up a mirror and letting them know they are not alone in their pain, in their disappointments. Concertgoers sing passionately along with her.

For anyone who has been wronged in love, she offers lyrics such as “You call me up again just to break me like a promise / So casually cruel in the name of being honest” and “You can plan for a change in weather and time / But I never planned on you changing your mind.” In their simplicity and clarity, she strikes chords with phrases such as “Time won’t fly, it’s like I’m paralyzed by it / I’d like to be my old self again, but I’m still trying to find it / After plaid shirt days and nights when you made me your own / Now you mail back my things and I walk home alone” and “You said it was a great love, one for the ages / But if the story’s over, why am I still writing pages?”

As Times podcast host Michael Barbaro, a self-confessed Swiftie, put it in talking with Brodesser-Akner: “the Taylor Swift project of internalizing pain and turning it into music has the effect that you’re describing on tens of millions of people. It makes them see anew a lot of the pain in their lives, to look it squarely in the face, and to try to better understand it and to have a catharsis around it.”

Now, that is not what is happening, I’m sure, with my six-year-old grandson. For him, I suspect, the simple music is the draw (though he sings along with some of the lyrics), along with the extraordinary staging and Swift’s amazing costumes. In those powerful lights, she is riveting, of course, whether she is wearing skin-tight sequined bodysuits or others filled with snake images – all of which suit her Barbie-like figure. She stuns us even in oversize chiffon dresses.

In her costuming, bright-red lipstick and glittering eye makeup she is something else, as well, something that I feared had disappeared among powerful women. She is remarkably feminine, a demeanor one might think would cost her among feminists and gay women. And yet, lesbian writer Kat Tenbarge writes of Swift: “It’s incredibly gratifying to feel a little seen, and feel a little understood, by an artist whose presence has guided you from adolescence to adulthood, like Swift’s has for me. In ‘Folklore,’ Swift rolled out a moody blue carpet that chronicles all the nuances of my life so far, and all the reward of having lived through them.”

Perhaps our culture has evolved from the time when such women felt compelled to chop short their hair, eschew makeup and dresses and other talismans of traditional femininity? One might ask whether Swift, with flowing hair hanging down to her mid-back and her stunning smile, has made it okay again to exult in being a woman, just as football star Kelce can feel free to cry in public and yet be as macho as they come.

Of course, feminism need not be incompatible with femininity. Just as Springsteen can look very much like a traditional working-class stud in T-shirts and jeans and yet sing the gay anthem “The Streets of Philadelphia,” so can Swift sport chiffon and still sing of injustices dealt to women in the workplace. Her song “The Man” says “… if I was a man, then I’d be the man.” Ironically, as my son-in-law pointed out, she is “the man” when it comes to running her career; she’s unquestionably in charge.

Certainly, earlier generations such as mine adored, emulated and sang along with their heroes on stages around the world. For me, at 69, there will never be equals to Dylan, Springsteen, Joan Baez, Neil Young, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, CSNY, Blind Faith, the Stones, Jefferson Airplane, Don McLean, Paul Simon, Janis, and so many more. At tumultuous times in my life – especially in my teens – they seemed so very important. In fact, my wife and I look forward eagerly to seeing the Stones live in June, though it’s both sad and funny that we got our tickets through AARP.

Even as the Taylor Swift phenomenon surpasses the legacy of her forerunners, at its base it is a powerful echo of them. She is a megastar because her work speaks to the needs, desires and struggles of her fans, much as that of earlier stars did to her fans’s parents. May her time in the sun last for a long while yet – at least to the day when my grandson understands her powerful and personal messages.