Americans seem more pessimistic than ever in recent memory — and it’s tough to see what will change that

By most measures of national economic health, things look pretty bright. And yet, Americans have become a nation of Gloomy Gusses, it seems. Just why goes some way toward explaining our troubling politics and our likely futures.

A couple recent polls – a national one released by The Wall Street Journal and a narrower one from The New York Times – both point to a surprising degree of negativity abroad in the land. And a few experts – as well as laymen – have offered concerning explanations of the results.

The Journal recently released results of a survey in which only 36% of voters said the American dream still holds true. This is down from 48% in 2016 (that fateful election year) and from 53% in 2012 in similar surveys. And it’s down substantially from a Wall Street Journal poll just last year in which some 68% said people who worked hard were likely to get ahead in this country.

The Journal observes: “… Americans across the political spectrum are feeling economically fragile and uncertain that the ladder to higher living standards remains sturdy, even amid many signs of economic and social progress.”

The American dream, as the pollsters from the University of Chicago’s NORC program working with the WSJ described it, is the simple notion that if you work hard, you’ll get ahead. And their question, from interviews with 1,163 voters, was whether that still holds true (36% said yes), never held true (18%) or, quite disturbingly, once held true but doesn’t anymore (45%).

Furthermore, half of those polled said that life in America is worse than it was 50 years ago, compared with just 30% who said it had gotten better. Asked if they believed that the economic and political system is “stacked against people like me,” half agreed with the statement, while only 39% disagreed.

The big question, perhaps an existential one for the 2024 presidential election, is “why such pessimism?” Moreover, how can Americans feel so down when macroeconomic measures are so up?

The national unemployment rate, for instance, sits at 3.9%, remarkably low by historic standards. And median weekly earnings of the nation’s 122.1 million full-time wage and salary workers are now 4.5 percent higher than a year ago, outpacing inflation (up 3.5 percent over the same period).

The Journal article suggests a few explanations. It quotes a 30-year-old Missouri fellow as saying: “We have a nice house in the suburbs, and we have a two-car garage … But I’d be lying if I didn’t say that money was tight.” For him and most of his neighbors, “no matter how good it looks on the outside, I feel we are all a couple of paychecks away from being on the street.”

Despite the extraordinary material amenities that most Americans now enjoy, thanks to technological progress and global economic health, that fellow said life is “objectively worse” than it was a half-century ago. He pointed to the decline of unions and the disappearance of pensions, things that helped his railroad-worker grandfather.

Others quoted by the WSJ similarly pointed to inflation, even though the rate of price increases has declined in recent months. Suggesting a lag in perception, the newspaper noted that inflation outpaced the gains in worker pay in 2022 for the second year in a row, and mortgage rates are at their highest level in more than two decades.

The results of a New York Times/Siena College poll, focused on six electoral swing states, likewise reflect gloomy outlooks. Eight in 10 respondents said the economy is fair or poor, with just 2% calling it excellent. Majorities of every group of Americans — across gender, race, age, education, geography, income and party — have an unfavorable view.

A Times editorial board member, Binyamin Applebaum, and Peter Coy, a former colleague at BusinessWeek now writing for the newspaper, offered some wisdom on the grumpiness.

Coy pointed to differing views of inflation between the average consumer and the number-crunchers. “To an economist, inflation is the change in prices,” he wrote. “So if prices go up sharply but then level off for a few months, the monthly inflation rate at that point is zero. There’s no more change in prices, right? But to most people, inflation is high prices. So they look at high prices in the supermarket or wherever and say, ‘That’s inflation!”

Furthermore, Coy pointed to home prices and mortgage rates, both up as affordability is way down. “Rents are also up. This is no problem if you already own, but it’s awful if you’re a young person trying to buy your first place,” Coy wrote. “That’s why you see TikTok talking about a Silent Depression; that might also explain why 93 percent of people 18 to 29 in a recent New York Times/Siena College poll said the economy was poor or only fair.”

For his part, Applebaum focused on the dark outlook for the future, a sense of dread.

He noted that an NBC News poll found that only 19% of respondents were confident that the next generation would have better lives than their own generation. “NBC said it was the smallest share of optimists dating back to the question’s introduction in 1990,” he said.

Applebaum’s conclusion: “For me, this is the great failure of the Biden administration and its economic policies: Americans simply aren’t convinced that the future is bright.”

This observation was supported by a crucial detail in the WSJ poll results. To 45% of the respondents in that survey, there once was an American dream but it has disappeared. And for 18%, it was all a lie, something never real.

Let’s add a few thoughts. First, widespread unaffordability of housing may be the single biggest tangible element contributing to the bad-feelings wave. After all, a key part of the American dream is owning one’s home, something that brings with it safety and promising educational prospects for a family.

According to the National Association of Realtors, the median price for an existing home — one that’s already standing, not new construction — came to $410,200 in June 2023, Bankrate reports. The news service reports that the figure is the second highest since the association started tracking the data. While down a bit from the all-time high of $413,800, at the peak of the housing boom in June 2022, it’s still in nosebleed territory for many.

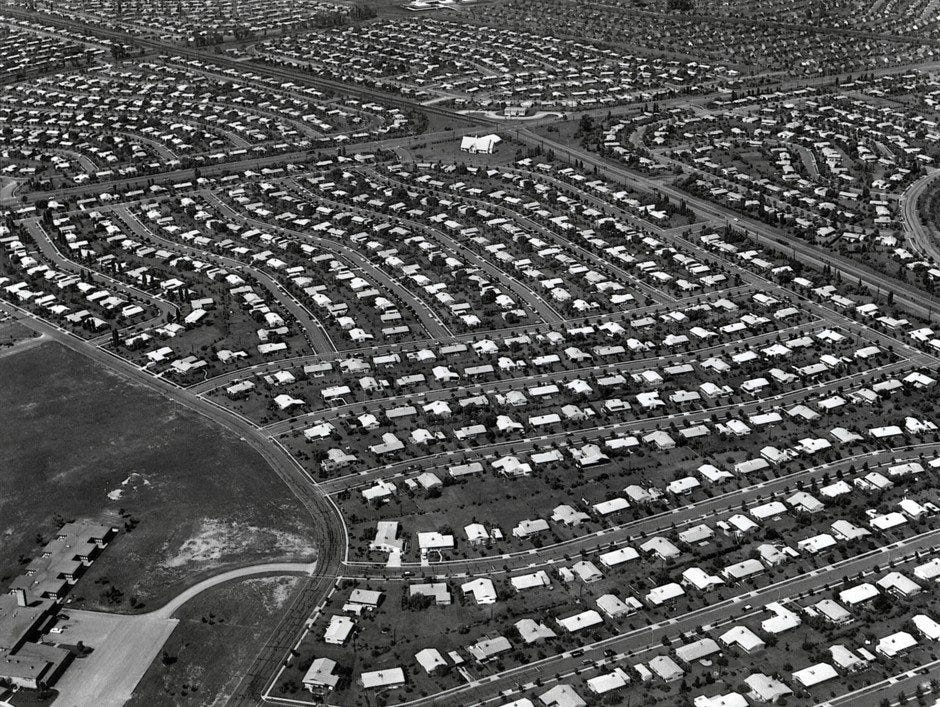

Those of us who recall the postwar developments such as Levittown remember a time when GIs with little assets but with steady jobs in the fast-expanding economy could afford homes. A home in such a development would sell for $8,000 in the late 1940s (or about $102,000 in today’s dollars). As Edward Glaeser recounted in Triumph of the City: How Our Best Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, the G.I. Bill and federal housing subsidies, trimmed the upfront cost of a house for many buyers to around $400 (or $5,100 today).

Where are today’s Levittown equivalents? From coast to coast, developers are keen to build homes that start at $500,000 or so. Are many building on the lower end? No. Indeed, the median price of an existing home in Levittown, New York, today, is $606,000.

Moreover, developers are not even building enough apartments for low-income earners – which could otherwise be steppingstones for affordable homes.

The Urban Institute and the National Housing Conference report that for every 100 extremely low income households, there are only 29 adequate, affordable, and available rental units. That means two parents who both work minimum-wage jobs might wait years to find a safe, affordable place to live with their two kids. With such high demand, why aren’t developers racing to build affordable apartments?

The answer: “building affordable housing is not particularly affordable,” the groups say. They point to a huge gap between what such buildings cost to construct and maintain and the rents most people can pay. “Without the help of too-scarce government subsidies for creating, preserving, and operating affordable apartments, building these homes is often impossible,” the groups say.

A related issue that likely contributes to national pessimism — at least among city-dwellers — is widespread homelessness. Walk the streets of just about many medium-size or large city in America and you are likely to come across people living in tents. The Department of Housing and Urban Development counted about 582,000 such homeless people in 2022, or 18 for every 10,000 Americans.

And homelessness is a product of both unaffordable low-end housing and a panoply of intractable social ills, including drug addiction and mental illness. With such highly visible and apparently worsening problems, is it any wonder that many Americans find optimism difficult?

In looking forward, too, education factors into the national mood. Higher education, after all, is perhaps the biggest driver of social mobility over generations. The average cost of a college degree now is $36,486 per student per year, with all costs included. Accordingly, the amount of debt most students must incur – something that can weigh them down for decades – is prohibitively high. The costs, of course, were far lower in past decades.

Finally, while crime rates in some respects have been dropping, gun violence has been rising. In 2020, gun violence became the leading cause of death for American children, The New York Times reported. In 2022 things grew worse: The number of children killed in shootings rose by almost 12 percent, and those wounded increased by almost 11 percent, the newspaper said.

Of course, mass shootings garner headlines, which hardly can only corrode the national mood. The national tally of such events now tops 600 and solutions that can curb them seem impossible to find. Tragically, the number of guns nationwide continues to climb.

Amid all this, we now face the prospect of a rematch between Joseph Biden and Donald Trump for the presidency in 2024. For all his policy successes – and measurable economic gains – Biden, now 81, is widely seen as just too old. Even though Trump is just four years younger, Biden often appears feeble in comparison to Trump. Neither is, say, a John F. Kennedy, whose youthful good looks mirrored the upbeat national mood of the early 1960s.

It’s hard to see what will lift the national outlook. A new generation of presidential politicians, those who project the optimism of a Kennedy or, on the other side, a Reagan? That would go some ways. But the tougher nuts to crack are the all-too- tangible ones of affordable housing and higher education, safety and better-paying and more secure jobs.