Professors at Arizona State University’s honors college were deeply troubled by plans for right-wingers Dennis Prager and Charlie Kirk to speak at a confab last February exploring “Health, Wealth and Happiness.” But their impassioned reaction raises important issues about just what free discourse on a campus means.

“Thirty-nine of [the college’s] 47 faculty signed a letter to the dean condemning the event on grounds that the speakers are ‘purveyors of hate who have publicly attacked women, people of color, the LGBTQ community, [and] institutions of our democracy,’ event organizer Ann Atkinson writes in The Wall Street Journal. “The signers decried ASU ‘platforming and legitimating’ their views, describing Messrs. Prager and Kirk as ‘white nationalist provocateurs’ whose comments would undermine the value of democratic exchange by marginalizing the school’s most vulnerable students.”

Despite that faculty outcry, the event, sponsored by the college’s T.W. Lewis Center for Personal Development, attracted 1,500 people in person and 24,000 online, according to Atkinson. She described the talks as part of a speaker series connecting students with professionals for career and life advice.

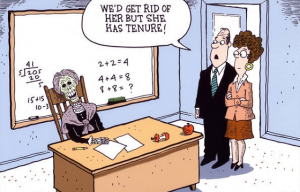

Now, in the wake of the flap, however, the university is shutting down the center, effective June 30. Atkinson, an alum of the college who made her name and fortune in healthcare real estate investing, will lose her job. And, in the WSJ piece, headlined “I paid for free speech at Arizona State,” she slams the university for its “deep hostility toward divergent views.” She concludes that “ASU claims to value freedom of expression. But in the end the faculty mob always wins against institutional protections for free speech.”

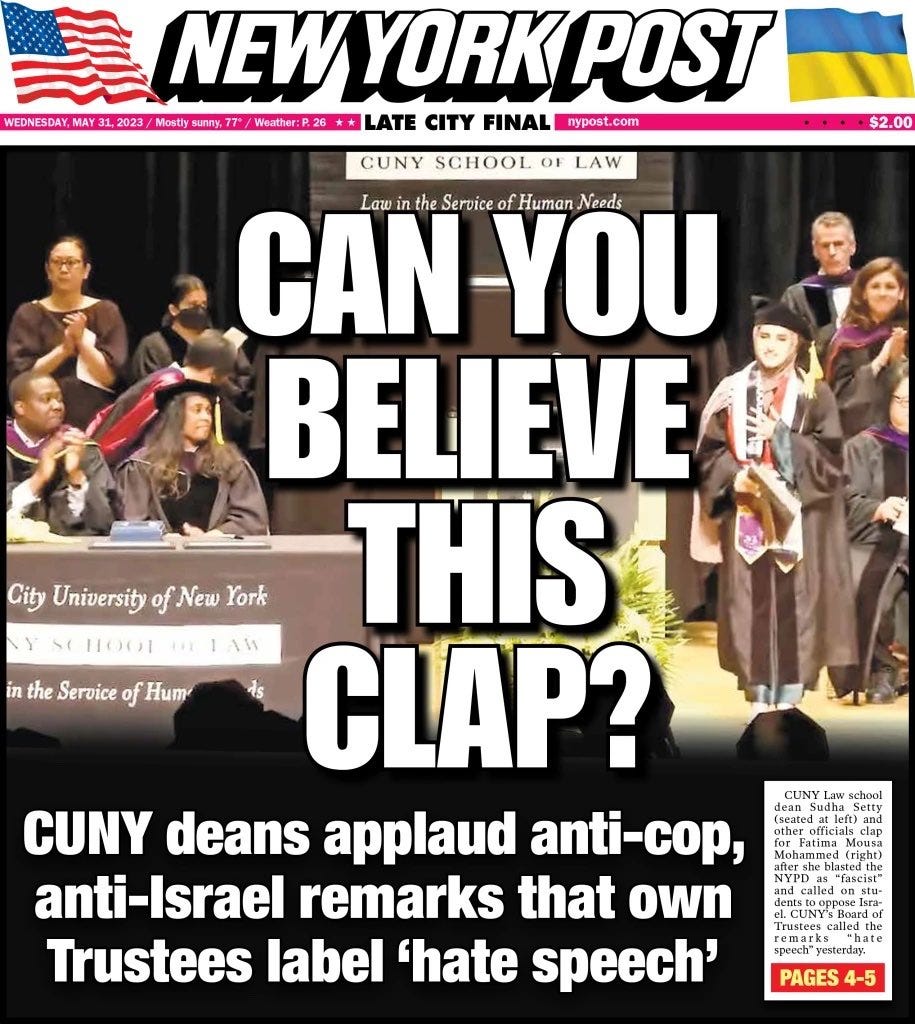

Among universities nationwide, ASU is hardly alone in battles over whether some speakers are simply beyond the pale. Debates over visitors of all stripes have roiled campuses from Princeton in the east to Stanford in the west. For a bit of detail, see “What Are the Limits of Free Speech?” While conservative speakers have been at the center of most of the hubbub, the occasional left-winger has slipped in, as happened at the CUNY law school with a pro-Palestinian’s vitriolic talk condemning Israel, capitalism and a host of other bogeymen. See “A Commencement Rant Suggests Poor Schooling.”

The brouhahas raise plenty of questions for anyone interested in open exchange on colleges. They go to the heart of what freedom of speech is and isn’t.

Here are a few such questions: At what point are faculty members being too protective of students in wanting to shut out speakers whose views — no doubt — will offend many? Are students so vulnerable that they should be shielded from obnoxious views? Would they be exposed to noxious notions through the Internet and other venues anyway? And is there anything preventing faculty from criticizing the speakers, essentially turning their appearances into teachable moments, occasions for poking holes in the most outrageous arguments?

Many provocative speakers – on both the left and right – are hardly unique or original in their views. Their opinions percolate about in the zeitgeist, almost always for ill, and are rarely avoided. Indeed, the ideas espoused by some of them have become mainstream in some partisan talking points in the already boiling presidential race.

Is it better to ban such folks or to have faculty members whom students respect intellectually disembowel them? Will reprehensible views go away when a campus here or a campus there simply bars the advocates? And does welcoming such folks reflect badly on a given campus, especially if the purpose of the invitation is for smarter folks to defenestrate their arguments?

Let’s stipulate that radio host Prager has outraged many folks. He condemned Covid lockdowns, lambasted same-sex marriage, and even criticized a Muslim congressman for using the Quran instead of the Bible in a swearing-in ceremony. Raised in an Orthodox Jewish household, Prager extols Judeo-Christian traditions above all others, a view that resonates with some but would hardly play well in much of the world outside of the West (indeed in most of the world, in sheer population numbers).

Similarly, let’s acknowledge that Kirk, the founder of Turning Point USA, seems like a throwback to an idealized 1950s. His attacks on feminism and “the transgender agenda” – whatever that is — likely appear wacky to many folks, though not to the future “trad wives” who attended sessions such as the recent Young Women’s Leadership Summit, held fittingly in Texas. Attendees heard about buying tampons and beauty products and other items from companies that market themselves as pro-Christian or anti-woke, as a Washington Post writer noted.

But are campuses, in fact, doing a disservice to their students and larger communities when they prevent them from airing their odd views? There’s no doubt that some views and some speakers are intolerable – one thinks of leaders of the KKK and Nazis on the right and some pro-Palestinian speakers on the left, of course. And attacking folks for their race, religion or sexual orientation in general should keep some speakers off limits.

But even in some of those areas, is it not risky to shut off discussion? For instance, the arguments for and against Critical Race Theory would seem to deserve a full airing. And, when it comes to religion, should there not be room for talking about, say, whether images deemed inappropriate by some Muslims should be shut out of art classes? And would discussions of cults benefit from the airing of such documentaries as Shiny Happy People, a critical exploration of a form of Christianity that some defend but others find odd and dangerous?

As to sexual orientation, many on the right are making hay of attacking homosexuality and transgenderism these days. Some folks, succumbing to the demagoguery of the day, apparently don’t or won’t grasp that respecting gays and transgender folks seems like basic decency. Should there not be room for education about such matters, even if it comes in a debate or counter-programming involving a Kirk or a Prager?

Plenty of odd and disturbing views are coursing through a troubled America nowadays, but it seems that campuses could harm students by not letting them get a full –- and critical — airing. Put them under the microscope, expose them to the hot lights of bright academics. Instead of banning the advocates, would we not be better off pitting them against intelligent opponents in settings where the vacuousness of their ideas could be exposed?

Yes, that is admittedly “platforming” them, as the ASU faculty noted. But have the Internet and social media not already platformed them far more effectively, giving people only one side of the story? Are campuses immune to noxious ideas just because they aren’t delivered in person?

Free speech is often not pretty. But does one defeat ugly ideas by simply shutting off some of the outlets in which exponents could espouse them? Would it not be better to expose racism, hypocrisy, venality, ignorance and such for what they are, holding them up to scrutiny on an enlightened campus?

Letting Kirk and Prager and their ilk speak while showing up the bankruptcy of their ideas would not win over all students. For evidence of their appeal, just look at their popularity in off-campus venues. Still, an intellectual free-for-all would offer a chance to win over the sharper students. There is such a thing as a battle of ideas, and these days the best ideas must be allowed to win.