As I sat entranced by Tchaikovsky performed by Russia’s Gergiev and Mariinsky Orchestra at Beijing’s sprawling and ultramodern National Center for the Performing Arts this weekend, I was struck again by the country’s stark contrasts. By the thousands, people here delight in orchestras, dance troupes and theater companies from across the world. Demonstrating its scientific prowess, China just last week launched a rocket carrying the Tiangong-1 lab module into orbit, a step toward a manned space station. And, economically, China’s robust growth is making the rest of the world pale.

As I sat entranced by Tchaikovsky performed by Russia’s Gergiev and Mariinsky Orchestra at Beijing’s sprawling and ultramodern National Center for the Performing Arts this weekend, I was struck again by the country’s stark contrasts. By the thousands, people here delight in orchestras, dance troupes and theater companies from across the world. Demonstrating its scientific prowess, China just last week launched a rocket carrying the Tiangong-1 lab module into orbit, a step toward a manned space station. And, economically, China’s robust growth is making the rest of the world pale.

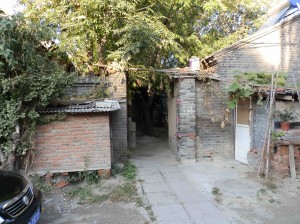

And yet, China is also a place where indoor plumbing is a dream for squatters and the poor who live in ramshackle houses, including some still scattered about the Tsinghua University campus. For all its openness to people and companies from around the world, the country still shuts out such powerful communication tools as Facebook and Twitter and muzzles its own knockoffs of such social networks. And university graduates who go to work for foreign companies in their offices here – whether media such as Bloomberg News or global manufacturers such as Procter & Gamble – can’t get needed Beijing residency permits, crucial papers that give them to right to do everything from buy cars to send their kids to public schools.

I suppose such contrasts – and contradictions – are nothing new here. Emperors and empresses lived in opulence so lavish that long canals were built to let them travel in comfort between palaces (this weekend, we visited one such canal linking the Summer Palace with a central Beijing spot). At the same time, peasants starved in the countryside. More recently, as a middle class has surged into prominence, residents in Beijing, Shanghai and other cities have been able to snap up spacious gated-community apartments, cars and other amenities they could scarcely imagine when they were young. Flashy shopping malls, many stocked with pricey western goods, fill architecturally fascinating towers that have risen by the hundreds in the last decade in Beijing. And yet, some of the poor in rural areas attend schools with cinderblocks for seats, no books and no real hope for the future.

I suppose such contrasts – and contradictions – are nothing new here. Emperors and empresses lived in opulence so lavish that long canals were built to let them travel in comfort between palaces (this weekend, we visited one such canal linking the Summer Palace with a central Beijing spot). At the same time, peasants starved in the countryside. More recently, as a middle class has surged into prominence, residents in Beijing, Shanghai and other cities have been able to snap up spacious gated-community apartments, cars and other amenities they could scarcely imagine when they were young. Flashy shopping malls, many stocked with pricey western goods, fill architecturally fascinating towers that have risen by the hundreds in the last decade in Beijing. And yet, some of the poor in rural areas attend schools with cinderblocks for seats, no books and no real hope for the future.

Economists measure disparities in income in societies, and China’s ranking is surprising. While the U.S. looks worse, at 39th place in terms of distribution, thanks to all those zillionaires President Obama wants to tax, China isn’t far behind, at 52nd place. This ranking, the Gini index, is based on fairly old data (from 2007 in China’s case), and I suspect the measure will worsen when newer numbers come in. But already it suggests that China’s flood of new wealth hasn’t lifted all boats. Indeed, China’s leaders are so concerned about disparities that they have banned certain words in advertising – “supreme,” “high class” and “luxury,” for instance – apparently believing that such terms only spawn dangerous envy.

Economists measure disparities in income in societies, and China’s ranking is surprising. While the U.S. looks worse, at 39th place in terms of distribution, thanks to all those zillionaires President Obama wants to tax, China isn’t far behind, at 52nd place. This ranking, the Gini index, is based on fairly old data (from 2007 in China’s case), and I suspect the measure will worsen when newer numbers come in. But already it suggests that China’s flood of new wealth hasn’t lifted all boats. Indeed, China’s leaders are so concerned about disparities that they have banned certain words in advertising – “supreme,” “high class” and “luxury,” for instance – apparently believing that such terms only spawn dangerous envy.

As for its ambivalent dealings with the West, China has long alternated between periods of openness and times of circling the wagons. Its leaders have adopted Western ways only to shrug them off. They have shut the borders when they felt the contacts were hurting them. These days, China is pushing its promising youngsters to learn English – teaching it from the earliest years – and facilities from the subway here to signs on school buildings, in stores and on major locations boast English. I am teaching in the Global Business Journalism program, an example of China’s openness, as Western journalists teach their techniques to Chinese graduate students. This sort of openness would have been unthinkable only a few decades ago.

Like any developing economy, China’s system has a long way to go. It has come remarkably far since it set out on the once-reviled capitalist road in the early 1980s. Even as it pushes ahead technologically – as symbolized by Tiangong-1, its gleaming towers in Beijing and the bullet trains that zip around the country – it will continue to grapple with problems spawned by income inequality. Growing – and sharing — the wealth, and opening the doors more to the outside are unlikely to proceed evenly. The march forward may be marked by occasional steps backward – as with the government’s attitude toward Facebook. But, unlike earlier times when China’s leaders sought to close the country off from the rest of the world, it may be that such insularity proves impossible in a globally integrated economy. For hundreds of millions of Chinese, the open door will lead to a dazzling future.

Like any developing economy, China’s system has a long way to go. It has come remarkably far since it set out on the once-reviled capitalist road in the early 1980s. Even as it pushes ahead technologically – as symbolized by Tiangong-1, its gleaming towers in Beijing and the bullet trains that zip around the country – it will continue to grapple with problems spawned by income inequality. Growing – and sharing — the wealth, and opening the doors more to the outside are unlikely to proceed evenly. The march forward may be marked by occasional steps backward – as with the government’s attitude toward Facebook. But, unlike earlier times when China’s leaders sought to close the country off from the rest of the world, it may be that such insularity proves impossible in a globally integrated economy. For hundreds of millions of Chinese, the open door will lead to a dazzling future.