The tale grows richer, deeper and more troubling in the Arizona State University flap over free speech. After my recent Substack commentary about the contretemps appeared, a few folks at the university got in touch. They, like me, were troubled by misrepresentations and omissions that, sadly, editors at The Wall Street Journal permitted to run in an op-ed in mid-June.

So far, the paper’s editors have not corrected or acknowledged the flaws. As time passes, it seems unlikely they will do so, regrettably.

To provide a fuller picture of this bit of myopia, I now share the information the ASU folks shared with me. The details offer a window into the thinking of some folks on the far right, folks whose feelings of persecution are, frankly, mystifying in light of their political strength in recent years. Indeed, the brouhaha reminds me of the Orwell quote, “The further a society drifts from the truth, the more it will hate those who speak it.”

So, let’s get to some truth – or, at least, facts — if we can.

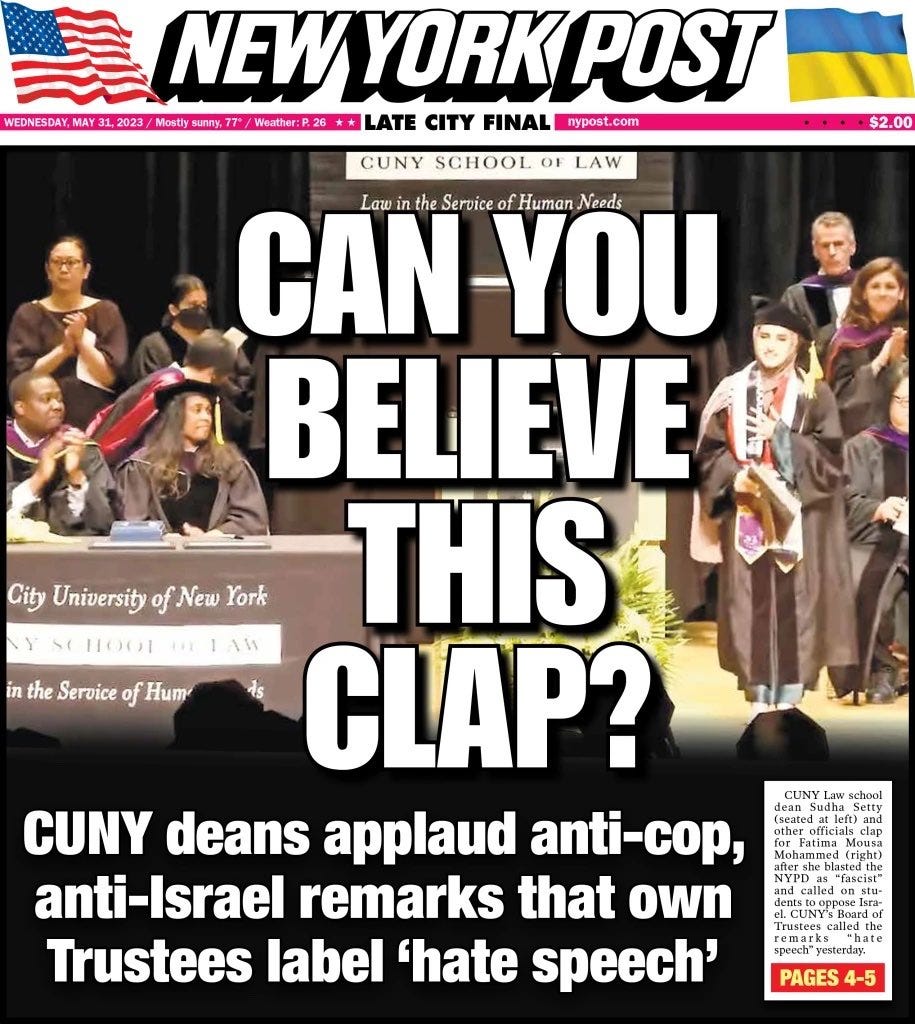

The T.W. Lewis Center at ASU’s Barrett honors college staged a session in February featuring a couple conservative speakers. Many members of the college’s faculty wrote a letter to their dean condemning the event, contending that two speakers were “purveyors of hate who have publicly attacked women, people of color, the LGBTQ community, as well as the institutions of our democracy, including our public institutions of higher education.” The letter-writers backed up their claims with links to comments by the speakers, radio host Dennis Prager and Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk.

That faculty letter prompted the center’s funder to pull the plug on his funds for it, leading the university to say it would close the center down at the end of June. Shortly before the closure, director Ann Atkinson wrote the WSJ op-ed headlined “I Paid for Free Speech at Arizona State.” It carried the subhed “The university is firing me for organizing an event featuring Charlie Kirk and Dennis Prager.”

So, the funder killed the center’s financial lifeline and yet the departing head of the place didn’t fault him, but rather the university. Indeed, aside from noting the name of the place, she didn’t mention the funder, real estate magnate T.W. Lewis, who subsequently felt compelled to issue a statement explaining why he had cut off the dollars. He bemoaned “the radical ideology that now apparently dominates the college.” For her part, Atkinson in her op-ed suggested that the “faculty mob” had defeated institutional protections on free speech.

An omission? A few key omissions? One would think so. Indeed, as a top university official wrote me, a bit of basic fact-checking by the WSJ would have prevented the problem.

To be sure, after Atkinson’s op-ed appeared the WSJ ran a letter from the ASU provost setting straight some of those omissions, including Lewis’s financial withdrawal. But there was no clarification from an editor, no admission that he had been hoodwinked.

To bring us up to more recent developments, Barrett faculty chair Jenny Brian and a couple colleagues wrote an op-ed of their own, published by the Arizona Republic on June 25, that noted that the profs had not sought cancellation of the Prager-Kirk session (a significant fact also omitted in the Atkinson piece). Instead, as they note, they had slated a teach-in prior to the session called “Defending the Public University” (a session also not noted by Atkinson). They maintained that they encouraged students to attend both events and claimed that many students did so. Nor were they party to the center’s shutdown.

This, of course, contradicts Atkinson’s claim in her WSJ op-ed that Barrett faculty intimidated students into not attending her confab. She offered little backing for that, other than to say she had heard from “many students.” To buttress her case, Atkinson reported that “older attendees” outnumbered students – though one wonders whether that’s simply because Prager, Kirk and such play better to an older crowd.

More disturbingly, Atkinson had reported that Prager got a death threat before the event. But, as she failed to note, violent threats were made against Barrett faculty members who signed the letter of condemnation.

As Brian and her colleagues wrote, “the most intense vitriol was directed toward Jewish and queer signatories, who received grotesquely antisemitic and homophobic threats against themselves and their families.” What’s more, Turning Point USA affixed the names of 34 signatories to its “Professor Watch List,” which Brian et al. described as an attempt “to silence left-leaning dissent on college campuses nationwide” – a list that they said subjects those on it “to years of threats and intimidation.”

So, one must ask a few questions here. Why did the WSJ not check out Atkinson’s claims before running her piece? Why has it not admitted since that, at best, the op-ed was marred by omissions? Why would a conservative funder not continue to support a center that did his bidding in scheduling a conservative event, despite the opposition by faculty members? And why would such a funder, claiming to support free speech, act to shut down a vehicle for it?

And what are we to make of the sense of victimization by Atkinson and others on the right, even though their session went forward without incident? Indeed, for free speech advocates, is it not heartening that both the Prager-Kirk programming and the Barrett faculty counter-programming went forward? Is that not the kind of discourse and exchange one wants on a campus? Should only one viewpoint be allowed here?

The failings in this flap seem to be many, but they don’t appear to be on the part of a faculty that seems concerned for all its students, including those for whom Prager et al. seem to have little compassion or even understanding. And, most glaring for journalists, the slips by the WSJ are troubling indeed. One expects better from an outfit that in so many ways is at the top of the heap.

Finally, one cannot avoid noting that there’s an ideological war being waged about campuses across the country, mostly involving politicians who are putting pressure on schools. Turning Point USA is a major combatant in this battle. Sadly, as a staple journalistic text noted, truth is often the first casualty in such a war.