Trump’s assault on higher education threatens to repeat them — or worse

Founded by slaveholder Thomas Jefferson in a state where 20 percent of the population is now Black, the University of Virginia might reasonably be a place that owes the state’s minority population something. And yet, only a fraction of the undergraduate UVA student body is Black (variously reported as 6.2 percent or 8 percent). And, after other minorities are counted, nearly 57 percent of undergrads are white, College Factual reports.

Diversity has been even more of a nonstarter among the faculty at Mr. Jefferson’s university. More than 82 percent of the faculty are white, according to College Factual, with the share of Black faculty variously reported as 5 percent or 9.8 percent.

So, it’s not terribly surprising that James E. Ryan, a UVA Law graduate, saw a need to boost diversity, equity and inclusion efforts when he took over as the school’s president in 2018. In his inauguration speech, Ryan committed to redressing UVA’s longstanding racial imbalances.

As The Chronicle of Higher Education reported, he said the campus community should “acknowledge the sins of our past,” including slavery, eugenics, and the exclusion of Blacks and women well into the 20th century. The university needed to recognize both Jefferson’s “brilliance and his brutality,” he argued.

Ryan also praised that fact that most UVA students at the time were women (a demographic reality at many campuses) and spoke highly about hundreds being among the first in their families to attend college. He warmed to the idea that the freshman class then was the most diverse in the university’s history.

As might be expected, this all didn’t sit well with some alums. A couple of the good ol’ boys in 2020 co-founded the Jefferson Council, an advocacy group that the Chronicle described as “committed to reducing the influence of progressive students, faculty, and staff, and restoring a more traditional UVa.”

The alums involved saw the university’s investment in DEI as wasteful, the news outlet reported, and they argued that it forced leftist dogma down the throats of Wahoos, as UVA students are known. They lambasted efforts to rename buildings, diversify admissions, and spend millions on DEI-focused administrators. Through blogs and social-media posts, they documented what they saw as the university’s mistaken priorities, and they put New Jersey-born Ryan into their gunsights.

With Donald J. Trump leaning on the school, the good ol’ boys have now won. Ryan quit after Trump’s Justice Department bridled at his refusal to dismantle the DEI programs and demanded his scalp, according to The New York Times. He stepped down rather than having the school risk losing hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funds, as other universities have.

“I cannot make a unilateral decision to fight the federal government in order to save my own job,” Ryan said in an email to the school community, The Wall Street Journal reported. “To do so would not only be quixotic but appear selfish and self-centered to the hundreds of employees who would lose their jobs, the researchers who would lose their funding, and the hundreds of students who could lose financial aid or have their visas withheld.”

Of course, this is just the latest university administrator’s head Trump or his supporters can claim. Their trophies now include Katrina Armstrong, driven out at Columbia in March after Minouche Shafik was forced out last August; and M. Elizabeth Magill, ousted at the University of Pennsylvania in December 2023, just a short time before Claudine Gay was driven out at Harvard. A fifth university chief, Martha E. Pollack surprised the Cornell University community in May by stepping down amid a threatened $1 billion in funding cuts.

Trump has put some $9 billion at risk at Harvard, with another $3 billion or so at risk at those above and other prominent schools. Those under the gun also include Princeton, Brown and Northwestern, as well as Johns Hopkins, a research gem where $800 million in cuts have led to hefty layoffs and where up to $4.2 billion in federal support is in danger.

The attacks are personal to a degree – Trump has a particular animus to Columbia, which once refused a $400 million land purchase he tried to foist on it (it’s not accidental that he cut $400 million from the university, or that the money hasn’t been restored even as Columbia largely capitulated to his demands). Also, recall that Trump himself was a middling transfer student into the University of Pennsylvania, where a professor of his said “Donald Trump was the dumbest goddamn student I ever had!’”

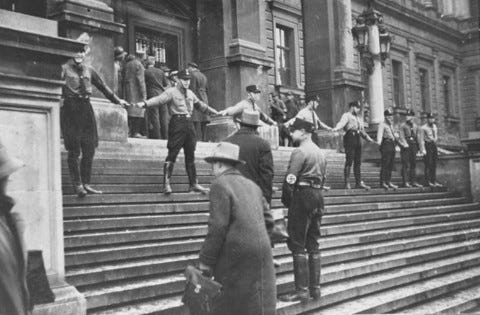

But the assaults also reflect the longstanding hostility rightists have had against the academic world, dating back at least to the days of Richard Nixon. Recall that Nixon famously said, “the professors are the enemy,” a phrase JD Vance reprised in late 2020 at a National Conservatism Conference.

Recall racist Gov. George Wallace’s assault on “pointy headed intellectuals,” which was mirrored decades later by Trump’s attack on “those stupid people they call themselves the elite.” The attack played well with Wallace’s undereducated followers back then and still resounds with Trump’s underschooled loyalists now.

It’s all something of a replay, though those earlier assaults had none of the teeth Trump’s latest ones have. The broad-gauge attack the president and his acolytes have mounted has been enormously costly. Consider what The Atlantic reported at the end of March:

“But college life as we know it may soon come to an end,” the magazine reported. “Since January, the Trump administration has frozen, canceled, or substantially cut billions of dollars in federal grants to universities. Johns Hopkins has had to fire more than 2,000 workers. The University of California has frozen staff hiring across all 10 of its campuses. Many other schools have cut back on graduate admissions. And international students and faculty have been placed at such high risk of detainment, deportation, or imprisonment that Brown University advised its own to avoid any travel outside the country for the foreseeable future.

“Higher education is in chaos, and professors and administrators are sounding the alarm. The targeting of Columbia University, where $400 million in federal grants and contracts have been canceled in retribution for its failure to address campus anti-Semitism and unruly protests against the war in Gaza, has inspired particular distress. Such blunt coercion, Princeton University President Christopher Eisgruber wrote in The Atlantic earlier this month, amounts to ‘the greatest threat to American universities since the Red Scare.’ In The New York Times, the Yale English professor Meghan O’Rourke called it and related policies ‘an attack on the conditions that allow free thought to exist.’”

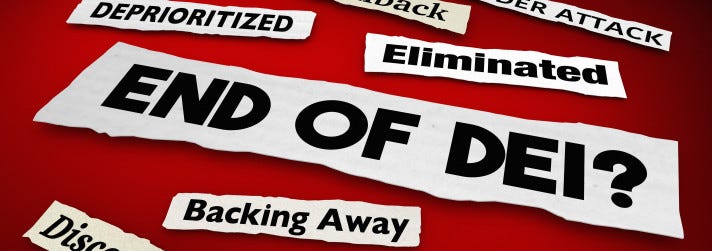

The administration’s twin rallying cries are fighting anti-Semitism and killing DEI. The former, of course, is just a fig leaf, a handy excuse for bludgeoning administrators because some students angry about the Gaza War misbehaved in the school year before last. Those protests were usually handled, if not always well, and mostly didn’t recur in the year just ended. Still, they are bogeymen the rightists can invoke as example of dissent they just can’t tolerate.

The DEI assault is more substantial. White Trumpians angry about minorities becoming more prominent feel disadvantaged, as they have ever since affirmative action began in 1965. Back then, President Johnson issued an executive order requiring federal contractors to take affirmative action to ensure equality of employment opportunity without regard to race, religion and national origin. Ever since then, any steps to give disadvantaged groups a leg up – and to adapt to our increasing national diversity – have been castigated by angry whites as unfair.

So, it’s no surprise that at UVA some white alums have resented the modest advances Blacks and other minorities have made and DEI efforts to help them. To them, 57 percent is apparently not a high enough share of whites among students; nor is 82 percent of faculty.

A third rallying cry among the Trumpians is intellectual diversity in the college communities. What that means is that professors are just too damn liberal — another longstanding canard — and they should be driven out in favor of rightists. That is taking root in some places. Just look at what Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has done with the New College of Florida in Sarasota, where ideologues have marched in, particularly as scholars in residence. The right sees this is as a model for remaking universities nationwide.

Judging from my days as a student and more recently as a professor, there are indeed plenty of liberals on faculties. That’s likely because liberals generally tend to be more adaptive to social change than conservatives, almost by definition, and being attuned to such change is natural in the academy. Still, there also are plenty of conservatives, and not only in economics departments and business schools. And is the liberal-conservative split even an issue in the sciences, tech and ag areas, for instance?

There are lots of scary elements about the changes Trump and his minions are enacting. One is a very conservative idea — that the drive amounts to social engineering by an elite in Washington — a Trumpian elite — not change coming from the grassroots. It is one thing if spontaneous change is demanded by the public around the country, in various states where legislatures fund education; another if it is directed by federal authorities.

Another troublesome factor is that many of the changes now being forced on private institutions are moving into the public ones. UVA is an example, but not the only one. We’ll likely see more such state universities in the dock going forward. More university presidents are likely to be driven out or quit under the pressure.

And where will this all leave students? Well, federal funding cuts will leave them with fewer intellectual opportunities as programs disappear. What’s more, in some states dominated by Trumpian rightists such cuts are being amplified by stinginess in state funding. As a result, many students are paying more for less.

In Nebraska, where I taught for 14 years, the state government’s contribution to the university system will rise roughly 0.6 percent in the coming year, far below the 3.5 percent increase that the Board of Regents had sought to account for inflation. The Trumpian Gov. Jim Pillen, who wanted the state to have “the courage to say no, and to focus on needs, not wants,” had originally pushed for a 2 percent cut, The New York Times reported.

“We will need to continue to reduce spending and make increasingly difficult choices to ensure fiscal discipline,” Jeffrey P. Gold, the University of Nebraska’s president, said before the regents voted to impose cuts and increase tuition. Students at the flagship campus in Lincoln will pay about 5 percent more.

It took many decades for higher education at both private schools and top-tier public ones, such as UVA, to develop into an international bragging point for the United States, a magnet for the world. That system, moreover, has long been the engine of American economic growth. Tragically, all that is under siege and it’s not clear how or when the damage we’ll see in the coming three and a half years can be undone.