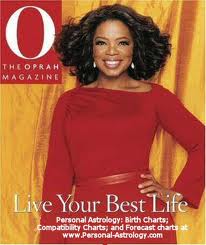

Oprah Winfrey, the nation’s trendsetter-in-chief, has given her blessing to Transcendental Meditation. The guru of Middle American women visited Maharishi University of Management and the Maharishi School for the Age of Enlightenment in Fairfield, Iowa, on Oct. 19. She meditated with several hundred fellow bliss-seekers in the women’s dome on the university campus, where devotees of both sexes practice transcendental meditation separately a couple a times a day under sprawling golden domes.

Oprah Winfrey, the nation’s trendsetter-in-chief, has given her blessing to Transcendental Meditation. The guru of Middle American women visited Maharishi University of Management and the Maharishi School for the Age of Enlightenment in Fairfield, Iowa, on Oct. 19. She meditated with several hundred fellow bliss-seekers in the women’s dome on the university campus, where devotees of both sexes practice transcendental meditation separately a couple a times a day under sprawling golden domes.

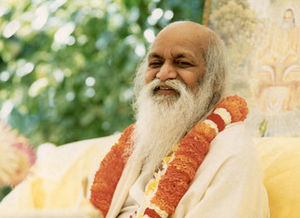

So, now that Oprah has embraced TM, the question is whether she can ignite a new boomlet in interest in the practice and the movement. She’s one in a long line of television and radio talk-show hosts who have fueled the movement’s growth for decades. TM’s ranks first surged in the 1970s, when Merv Griffin helped whip up enthusiasm for it among Baby Boomers. He showcased the movement’s guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and, like so many other celebs, took up the practice himself. More recently, shock-jock Howard Stern’s longstanding support has helped keep long-waning interest in the practice alive.

Can Oprah do for TM what she did for marathon-running and weight loss? Or, will her efforts for the practice go the way those enthusiasms have gone for her – short-lived at best? And what, if any, effect will she have on the town of Fairfield, home of the all-important U.S. arm of the movement? I’m especially interested because for the better part of the last two years I have been putting together a book on the town, looking at how the movement has changed this quintessential piece of Middle America, and looking at the movement’s ups and downs and prospects through that local lens. The University of Iowa Press will be publishing the book.

Can Oprah do for TM what she did for marathon-running and weight loss? Or, will her efforts for the practice go the way those enthusiasms have gone for her – short-lived at best? And what, if any, effect will she have on the town of Fairfield, home of the all-important U.S. arm of the movement? I’m especially interested because for the better part of the last two years I have been putting together a book on the town, looking at how the movement has changed this quintessential piece of Middle America, and looking at the movement’s ups and downs and prospects through that local lens. The University of Iowa Press will be publishing the book.

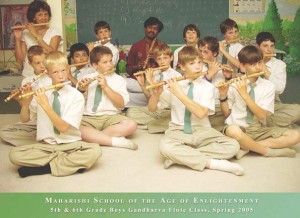

Oprah’s staff, reportedly, had been working on an hour-long program about Fairfield before her arrival. The TV guru was quoted saying the little farm town that TM has transformed has been a “best-kept secret” but won’t be for long now. With a camera crew in tow, she visited the school, where uniformed youngsters in grades K-12 learn a lot about meditation, their guru’s all-embracing worldview and subjects such as Sanskrit, along with reading, writing and arithmetic. At least one report quoted Oprah as saying, “some people are working toward raising consciousness but the MS students are living raising consciousness.”

Certainly, the Boomers who dominate the graying movement must hope that Oprah’s fond attention will provide a shot of adrenaline. Even before the Maharishi died, in 2008, interest in TM-style meditation had been declining, at least in the U.S. The movement’s ranks have shrunk from the peak in the 1970s, even as interest in meditation generally has grown and gone mainstream. Enrollments at the Maharishi School – mainly made up of children of Boomer adherents who moved to Fairfield to follow the guru – have slid. Enrollment at the Maharishi University of Management stands at 1,268 at the moment, though the undergraduate total is a modest share of that.

Certainly, the Boomers who dominate the graying movement must hope that Oprah’s fond attention will provide a shot of adrenaline. Even before the Maharishi died, in 2008, interest in TM-style meditation had been declining, at least in the U.S. The movement’s ranks have shrunk from the peak in the 1970s, even as interest in meditation generally has grown and gone mainstream. Enrollments at the Maharishi School – mainly made up of children of Boomer adherents who moved to Fairfield to follow the guru – have slid. Enrollment at the Maharishi University of Management stands at 1,268 at the moment, though the undergraduate total is a modest share of that.

On the plus side for backers, Oprah certainly is the Merv Griffin of today. Her influence on book sales is legendary. A guest shot on her long-running show meant instant fame and she launched several other media bigwigs. She has an especially passionate following among women, prime recruits for stress-reducing techniques such as TM.

But it’s also possible that Oprah’s kiss could be losing its power. Her programming is no longer on network, so her audience will be smaller than when she could launch an author — or another talk show host — into the stratosphere. Her embrace of meditation, too, is familiar to fans, since she has encouraged the practice for several years – even if her explicit passion for the TM variety seems fairly new. And, most troublesome of all for movement backers, there’s no giggling guru for her to put on the air.

But it’s also possible that Oprah’s kiss could be losing its power. Her programming is no longer on network, so her audience will be smaller than when she could launch an author — or another talk show host — into the stratosphere. Her embrace of meditation, too, is familiar to fans, since she has encouraged the practice for several years – even if her explicit passion for the TM variety seems fairly new. And, most troublesome of all for movement backers, there’s no giggling guru for her to put on the air.

For good or bad, TV loves a personality and so do movements. Even if TM’s twenty-minutes-twice-a-day meditative practice is as effective as the enthusiasts say, the movement lacks a charismatic personality who can rally followers. There’s no one exuding humor, wisdom and warmth — as the guru did — to adorn Oprah’s couch. There’s not even someone who can jump up and down on a sofa, a la scientologist Tom Cruise. Without that, TM could come across as just another meditation approach, not much different from what one could sign up for at many local gyms, except that TM usually costs more.

Whether it’s a short-lived boomlet or a jumpstart to a new enduring wave of growth, Oprah’s blessing can’t hurt. Certainly, she will put Fairfield on the map anew. She could even help the town attract some new residents. It will make for a fascinating discussion in my forthcoming book. Maybe even Oprah will find it worth reading.