The death of a brilliant colleague highlights our losses in media

In the opening issue of The Pennsylvania Magazine, a monthly published from January 1775 until July 1776 in Philadelphia, editor Thomas Paine wrote: “A magazine, when properly conducted, is the nursery of genius; and by constantly accumulating new matter, becomes a kind of market for wit and utility.”

As a modern nursery of genius, there were few equals to BusinessWeek in its heyday, a couple centuries after Paine’s words were published. BW garnered National Magazine Awards four times between 1973 and 1996. From 1958 to 2004, it picked up nine Gerald Loeb Awards, regarded as the Pulitzer Prizes of business journalism, including five in the glory days between 1987 and 2004. Since being sold to Bloomberg News in 2009 and rechristened as Bloomberg Businessweek, it has picked up another couple NMAs and several Loeb Awards, including two this year.

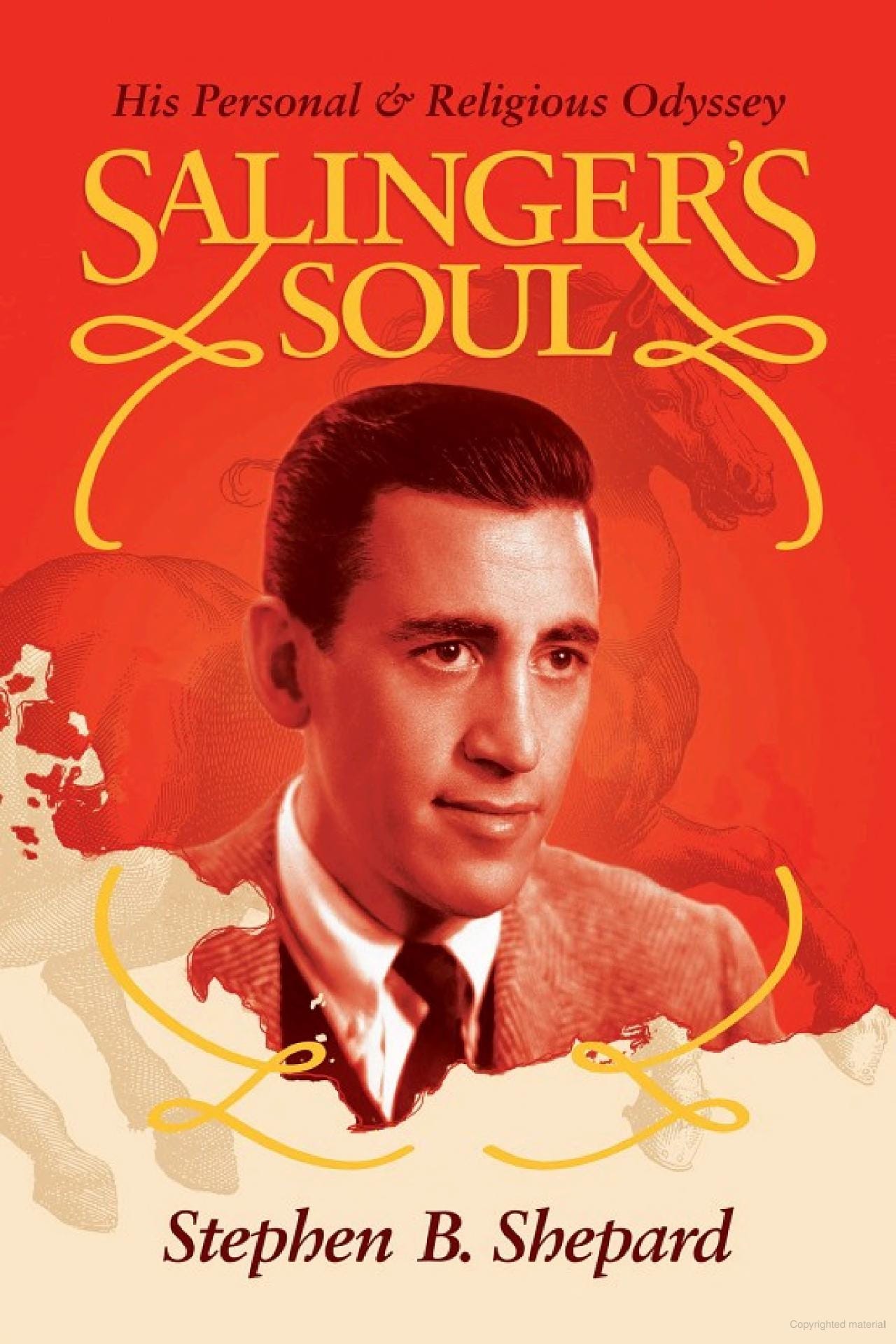

Alums of BW – graduates of that “nursery” — have gone on to illustrious stints at The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, Reuters, and The New Yorker, as well as online outfits including Poets and Quants, and elsewhere, including Bloomberg, of course. Some moved into substantial academic careers, including longtime editor Stephen B. Shepard, who founded and led a journalism graduate school at the City University of New York. Others have become novelists or gifted nonfiction authors. All of their work has been filled with wit and utility, indeed.

As someone privileged to work for the magazine for 22 years, until 2009, I was reminded recently of the place’s unique culture, sadly, by the death of a colleague there. Chris Power, a BW stalwart and international editor for most of the best years, died on Oct. 13 at 68. His passing drew more than 120 comments on a BW Friends site, most celebrating his wit, his skills, his easy way with people and his remarkable intellect. Some referred to his short stature – something he joked about – which reminded me of how a colleague once described Chris to me: “5-foot-3-inches of brain.”

Another coworker, a man I succeeded as Chief of Correspondents, described Chris as “an excellent editor who knew when to push fellow journalists to do their best work,” adding “he was always the gentleman.” Saying he was blessed to work with 35-year BW veteran Chris for decades, he added that “a key piece of what BusinessWeek was is now missing.” Yet another workmate called him “smart, fast and unflappable, no matter how tough the story or tight the deadline; all around one of the best.” Still another called him “the kindest, gentlest and cleverest editor I had.”

As Chris guided stories that a copydesk veteran called beautifully edited, he did so with style. “But most of all, I’ll remember Chris dropping by the desk and doing his soft shoe,” she wrote. “Even under the tightest of deadlines, he could lighten a heart.” At a goodbye party for a former top editor bound for Texas, another colleague reminisced about how the folks were all given hats. “When it was Chris’ turn to talk, he came up hatless and said, ‘When you’re 5’3”, you know better than to wear a cowboy hat,’” he wrote. Yet another former workmate wrote of Chris’s recipe for an extra-dry martini: “pour the gin, wave the vermouth bottle over the glass.”

The extraordinary outpouring of respect, affection and admiration for Chris reflected well on him, of course. But it also said a lot about the collegial and high-powered culture at BW, something that our top editor – Steve Shepard – fostered.

Sure, people brought a lot of brain power to the job. Our chief economist had a Ph.D. from Harvard, our finance editor earned his from The New School, others there had taught at Columbia, and the staff was filled with Ivy Leaguers of all sorts. As a magna cum laude graduate of Harvard who had been trained by Jesuits at Boston College High School, Chris fit in. He “was one of the gifted minds that made BusinessWeek BusinessWeek,” as one commenter put it.

But brains weren’t enough. To work at BW, you also had to be able to get on well, to work in a group, to produce the best damn stuff we could. When candidates interviewed for jobs, they would sit down with as many as a half-dozen people, I recall. The book, as we called it, was a team effort. “Chris was always smart, funny and – most vital to a young reporter trying to find her footing – helpful,” one former colleague wrote. “Farewell to a true gentleman!”

It was no wonder that BW won so many awards. It’s no wonder that it produced such good work.

Sadly, as veterans of the glory days are aging, we are seeing our numbers decline. The man who hired me (Keith Felcyn) died last year, as did a former assistant managing editor (Dave Wallace) and a former Tokyo bureau chief (Robert Neff). Earlier, we lost a former science editor (Emily Thompson Smith), a former managing editor (Jack Dierdorff), a much-respected Washington bureau chief (Lee Walczak) and a finance editor (Chris Welles). Such things are inevitable, of course, as the clock ticks on us all.

But, more than just the passing of such admired and often beloved people, these losses say something about the declines we are seeing all around in journalism. I can’t speak to the culture of Bloomberg Businessweek, but I suspect it’s rather different than the old BW (for one thing, Bloomberg let go or reassigned much of the staff and, for another, the magazine is entirely online now, so we don’t see the powerful blend of imagery and text that helped tell stories so well).

On a more troubling point, even with the exceptional journalism machine of Bloomberg News behind it, BBW and other magazines have lost the extraordinary power and reach they once had. It’s been a long time since they could make big-name CEOs and politicians alike anxious when that was appropriate, and their influence on public attitudes is dubious at best (as is the case with many newspapers).

Thanks to the Net and political changes, so many big-name publications in journalism have seen their influence shrivel. Organizations for which credibility, fairness and thoroughness were core values have lost subscribers and seen their staffs shrink, their economic wellbeing eroded. Today, lies from those at the top levels of politics gain traction because on the Net all voices seem equal and the loudest and least credible don’t even bother going through the responsible media. Instead, they take their distortions and distractions directly to the public.

Consider the appalling list of media outlets that have bent the knee to Donald J. Trump and whose inclination will be to pull punches. Paramount agreed to pay $16 million for a Trump library to settle an absurd CBS case and now the company and network are owned by Trumper David Ellison. He installed rightwing opinion journalist Bari Weiss as editor-in-chief at CBS News and is now pursuing an acquisition of CNN, jeopardizing its independence. ABC similarly agreed to pay $16 million to settle another dubious Trump lawsuit.

The broader media have similarly acquiesced. Facebook parent Meta agreed to pay $25 million and X $10 million, both related to lawsuits over the post-Jan. 6, 2021, suspensions of Trump accounts. Alphabet, the parent of Google and YouTube, agreed to pay $24.5 million to Trump and others over a similar suspension.

Encouragingly, Trump’s legal assaults on some media outlets have gone nowhere. This year, he sued The Wall Street Journal, a Fox property, in July over his 2003 letter to pedophile Jeffrey Epstein, a longtime friend of Trump’s. He’s seeking $10 billion. The president also sued The New York Times, demanding $15 billion for allegedly undermining his reputation with stories raising questions about his business acumen.

While he filed the defamation suits in federal court in Trump-friendly Florida, he’s been set back in both. Lawyers for the WSJ have filed for dismissal of that case, while Trump was forced to refile the Times case after a judge threw out his original 85-page complaint, saying it was laden with “florid and enervating” prose. The judge wrote: “A complaint is not a public forum for vituperation and invective.”

But Trump has a long history of using the courts – or trying to do so – to intimidate the press. In 1992, a colleague at BW, Larry Light, got hold of financial information about Trump that showed he had a negative net worth. As recounted by another colleague, Light’s inquiries drove Trump to march into Shepard’s office at BusinessWeek. There, the future president (whose companies went through six bankruptcies) launched into a three-hour tirade that included an anti-Semitic gibe about Light (who was, in fact, Episcopalian). Trump also threatened to sue but backed off after our lawyer told him his finances would then be opened to public disclosure in court.

Our editors at BusinessWeek and its owners at McGraw-Hill were not cowed or beholden to Trump. Shamefully, some of today’s media leaders are. Consider, for instance, Time owner and billionaire Trump backer Marc Benioff, under whose leadership the magazine recently replaced a jowly cover photo of the president that offended him with a more complimentary one. Benioff, who acquired Time in 2018, recently flip-flopped on backing Trump’s since-abandoned plans to deploy National Guard troops to San Francisco.

Much has changed in the media since Chris Power and leaders of his caliber set a demanding standard at BusinessWeek. Some magazines – The Atlantic and The New Yorker, for instance – and newspapers such as The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal continue to prize careful and thorough, if critical, journalism. Indeed, I am indebted to The Atlantic for the Paine comment, which appears in its wonderful November issue, which is devoted to the founding of the United States 250 years ago next year.

But the ability of such outlets to act as a check on unbridled power-seeking and self-dealing by Trump and his minions has been gravely diminished as much of the public and GOP politicians seemingly turns a blind eye on the excesses. In their war on the press, the rightists have sadly succeeded in defunding NPR, a key source of independent news. And the marketplace has savaged the economics of so many other media outlets.

Will some magazines – whether online or in print – remain or ever again become nurseries of genius? Some may. But Chris’s passing is yet another troubling sign of the passing of an era.