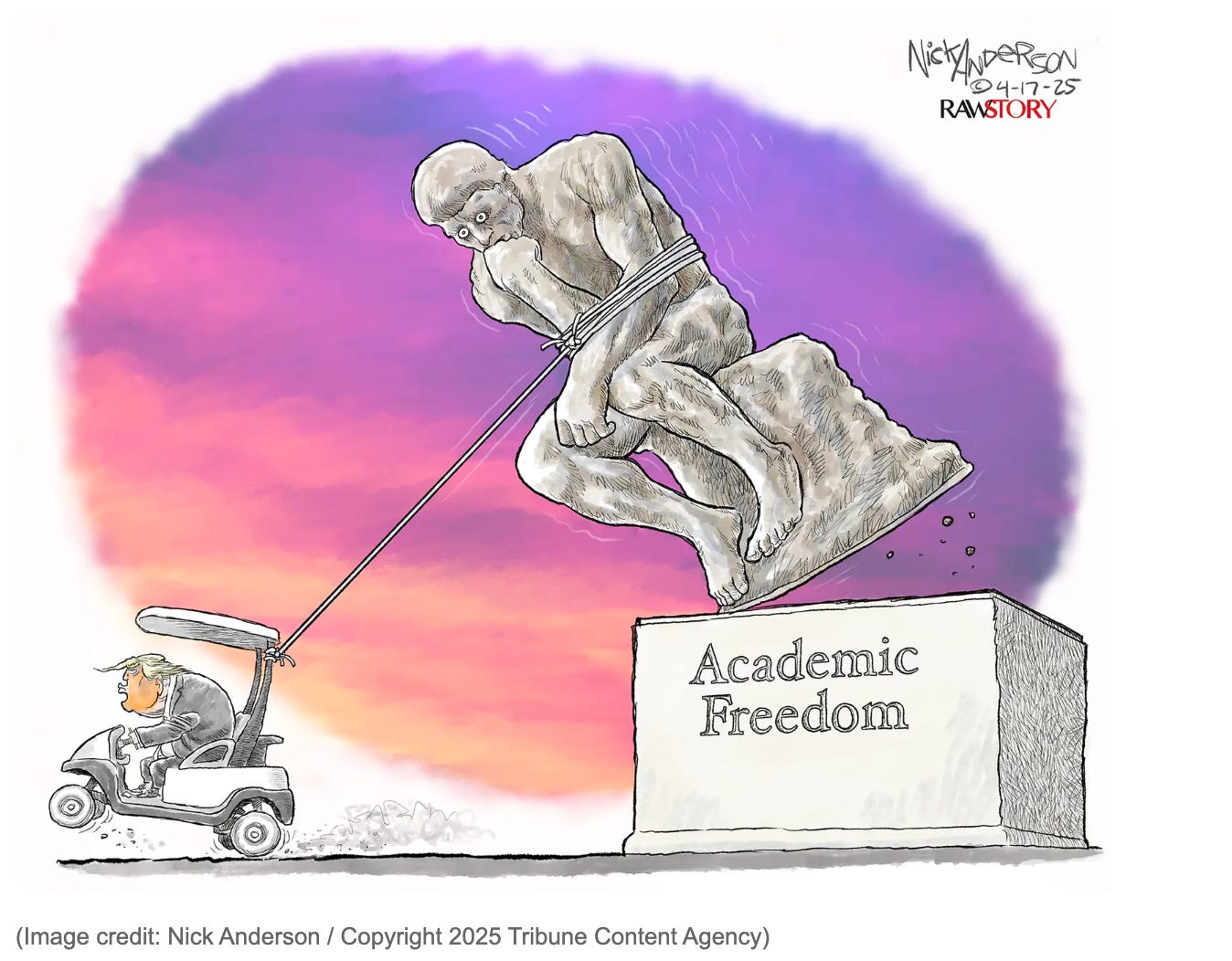

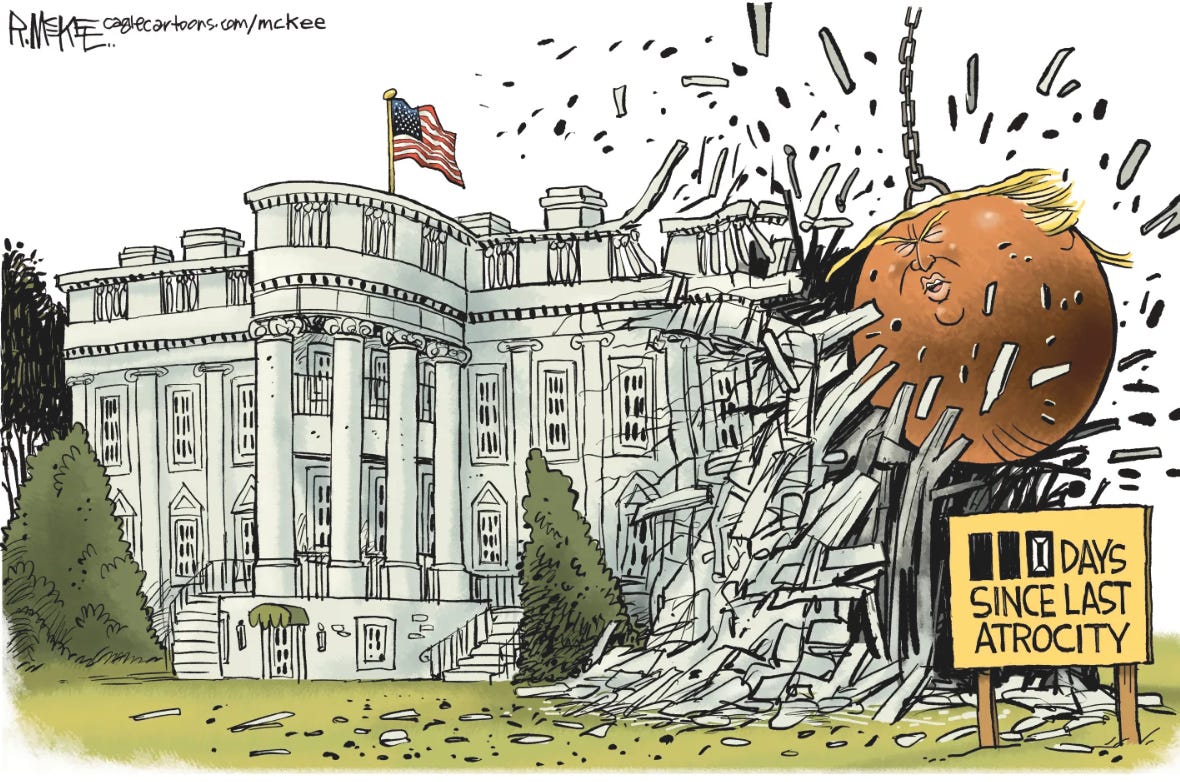

Trump and his enablers seem to exult in it

Twenty-six years ago, Holocaust survivor and Nobelist Elie Wiesel gave a speech in the East Room of the White House about indifference. He called it a “strange and unnatural state in which the lines blur between light and darkness, dusk and dawn, crime and punishment, cruelty and compassion, good and evil.”

Today, we have a president who seems the embodiment of Wiesel’s comment. The latest and saddest case in point: a 20-year-old National Guardswoman who was killed on a pointless domestic mission this president ordered up. His reaction: he spoke about his election results in her home state of West Virginia.

When asked if he would go to the funeral for Specialist Sarah Beckstrom, Donald J. Trump’s response was: “I haven’t thought about it yet but it certainly is something I could conceive of. I love West Virginia. You know, I won West Virginia by one of the biggest margins of any president anywhere.”

So, a woman not even old enough legally to drink is killed while she is far from home on this man’s bizarre orders to install Guardsmen on the streets of Washington, D.C., and Trump’s reaction is to talk about himself. Is that not the personification of a “strange and unnatural state?”

Indeed, is that not just indifference, but callous indifference?

But Trump’s indifference and that of his minions, of course, is deeply rooted. It begins in a wholesale blindness to facts. Consider the facts involved in the admission to the United States of the former Afghan fighter Rahmanullah Lakanwal, who shot Beckstrom and another Guardsman now battling for his life. To Trump and his FBI chief, Kash Patel, it was all the fault of Joe Biden.

So, what actually happened, so far as we know now?

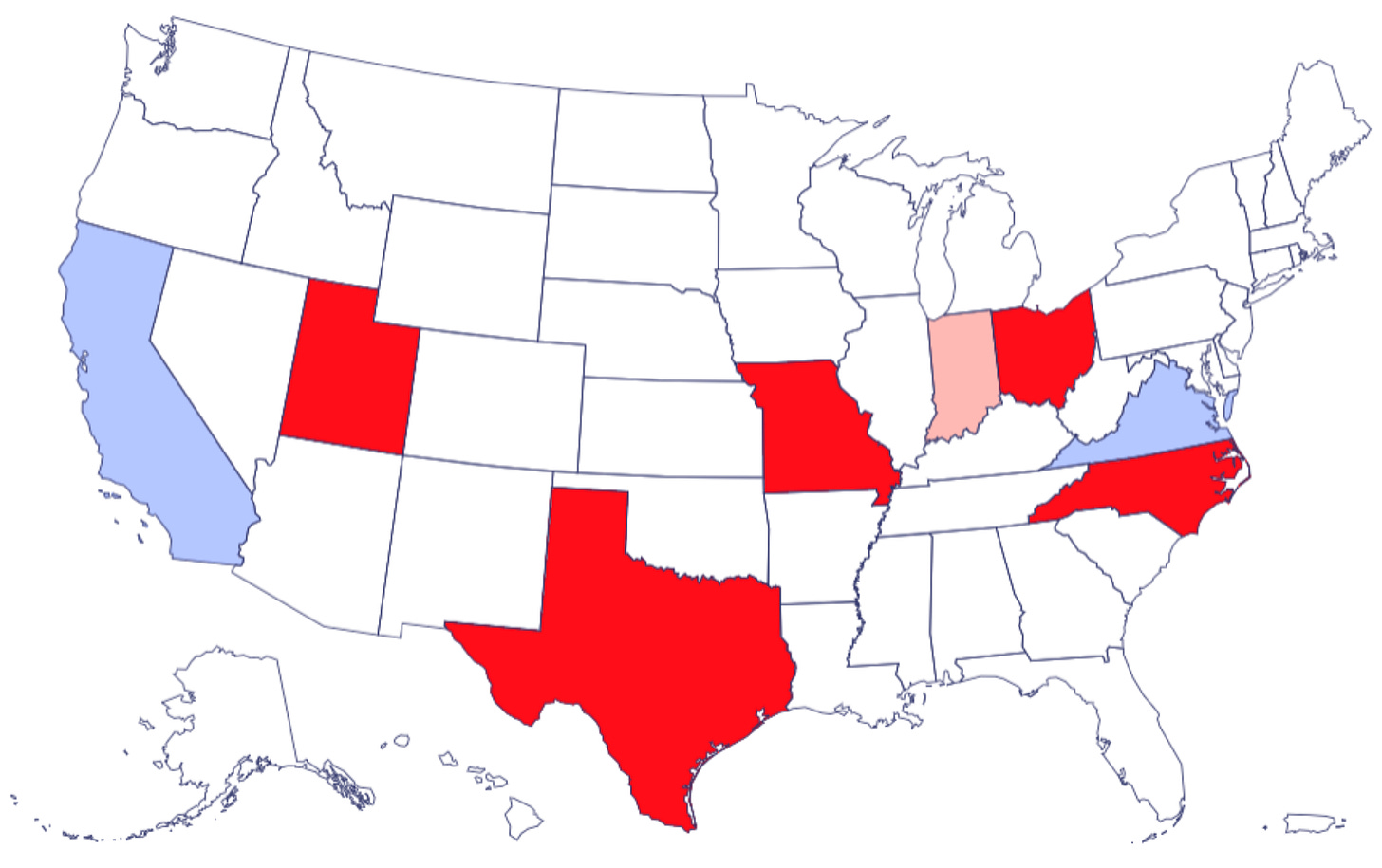

Lakanwal, now 29, was admitted to the U.S. in 2021 after working for the CIA in his homeland. He was part of the Operation Allies Welcome program (which later evolved into the Enduring Welcome program), under which some 190,000 Afghans were admitted to the U.S. In Afghanistan, Lakanwal was a member of a Zero Unit group, one trained for nighttime raids targeting suspected Taliban members and said to be involved in widespread civilian killings, according to The New York Times.

It’s likely that Lakanwal was one of only 3,300 of those refugees that year who were granted a “special immigrant visa,” ABC News reported. That status would have expedited his entry because of his employment with agency and would have involved vetting.

Quoting an unnamed senior U.S. official, ABC reported that Lakanwal had been vetted at one point by the National Counterterrorism Center and “nothing came up” during that review. The official added that “he was clean on all checks.”

Indeed, the Afghans underwent “rigorous” vetting to ensure they did not pose a national security threat, NPR reported. Some 400 personnel across U.S. agencies conducted checks that involved “biometric and biographic screenings conducted by intelligence, law enforcement, and counterterrorism professionals,” according to the Department of Homeland Security. “This process includes reviewing fingerprints, photos, and other biometric and biographic data for every single Afghan before they are cleared to travel to the United States.”

After some Republicans charged that the vetting was inadequate, the DHS Office of Inspector General released a report that admitted to some failings, including data inaccuracies in some files of Afghans. But another report, released in June by the Department of Justice, looked at the FBI’s role in the vetting and concluded: “Overall, we found that each of the responsible elements of the FBI effectively communicated and addressed any potential national security risks identified.”

And yet, FBI Director Patel claimed that the Biden administration did “absolutely zero vetting” of this group.

Moreover, Lakanwal would have undergone more review as part of his application for asylum in the U.S., an application that officials in the Trump Administration – not Biden’s – that was approved in April.

Confronted with such information, might Trump have said something sensible, such as saying the tragic situation merited a complete investigation? Might he have said his administration would probe this to see how Lakanwal may have posed a danger? Nope. Instead, Trump’s reaction was indifference to the truth – and hostility to the journalist bringing it up to him.

“Your [Department of Justice Inspector General] just reported this year that there was thorough vetting by DHS and by the FBI of these Afghans who were brought into the U.S.,” CBS News reporter Nancy Cordes said. She asked why, then, did Trump blame the Biden administration.

“Because they let him in, are you stupid? Are you a stupid person?” Trump responded. “Because they came in on a plane along with thousands of other people that shouldn’t be here and you’re just asking questions because you’re a stupid person.”

Angrily determined to avoid any responsibility? Indifferent to the truth?

Of course, Lakanwal’s actions were reprehensible, horrific, wholly unjustified. Still, initial reports suggest he was mentally ill, perhaps scarred by his experience in the Zero Unit. Did any of that come up in his asylum case just this past spring? Were there failures on the part of either the Biden or Trump Administration officials? Should they be investigated?

There is much we don’t know and that may yet be revealed, particularly about this killer’s mental problems. But we do know one other point: Specialist Beckstrom and her colleagues in the Guard had no business being in harm’s way in Washington, D.C. They were and are part of little more than a stunt by the president to use military forces on American streets, a foolish bit of optics that now has proved deadly.

Trump, of course, cannot see that as a mistake. Instead, his reaction is to boost the number of guards on the streets by another 500, on top of the 2,000 already there. Might that create more opportunities for bloodshed? Might we see more assaults, perhaps even some by understandably edgy Guardsmen who, after all, are not trained police officers?

Remember, too, another case of callous indifference by Trump and his minions. He ordered up attacks on suspected drug smugglers in international waters without proof, without trial and without mercy, killing more than 80 people so far. In the first of such attacks, on Sept. 2, Trump’s Secretary of Defense – who styles himself a Secretary of War – ordered that every one of 11 people on the boat be killed. “The order was to kill everybody,” an official told The Washington Post.

So, in that attack as a couple survivors clung to smoldering wreckage, the commander involved ordered a second missile strike. The survivors were blown apart in the water.

Callous? Indifferent? Seems like the very definition of it.

Because the U.S. is not at war with another nation in the area, killing anyone in such boats “amounts to murder,” a former military lawyer who advised Special Operations forces for seven years told the Post. Even if the U.S. were at war with drug traffickers, an order to kill all of such a boat’s occupants if they were no longer able to fight “would in essence be an order to show no quarter, which would be a war crime,” said Todd Huntley, who now directs the national security law program at Georgetown Law.

And yet, Trump shows no remorse, not the barest concern for the loss of life. Instead, he brags about how many Americans he claims to be saving from drug addiction deaths. Is there evidence of that? We haven’t seen it yet.

Of course, still more callous indifference is apparent every day that ICE officers disrupt families by hauling off immigrants. This is often without any due process, sometimes even in contravention of court orders. The latest case: Any Lucia Lopez Belloza, a 19-year-old Babson College student who was snatched as she tried to board a plane to visit her family in Texas about a week before Thanksgiving.

It appears that Lopez Belloza, whose family hailed from Honduras, had entered the U.S. about 11 years ago, when she was 7 or 8. ICE officials told The Boston Globe that the woman was subject to a deportation order dating back to 2015, although her lawyer said the family had asylum proceedings underway until 2017, when their application was denied. Still, they were assured that there were no deportation orders in place, the lawyer said.

Moreover, a federal judge on Friday, Nov. 21, ordered that Lopez Belloza not be deported from the U.S. or transferred outside the state of Massachusetts – an order that appears to have meant nothing to ICE. At around that time, according to the Austin American-Statesman, ICE was flying Lopez Belloza to Texas. And by the following Monday, she was in Honduras with her grandparents.

Indifferent to the hopes and dreams of a promising college student? Callous?

Well, consider the comments of Border Patrol Operations Commander Gregory Bovino. His reply to a news report about Lopez Belloza could not have been colder.

“Illegal aliens are just that despite age and educational status,” Bovino wrote on X. “Why even mention this illegal alien was an 18 year old [sic] college student? Completely irrelevant except that an illegal alien may have taken a university slot from an American citizen.”

Wiesel in his 1999 spoke of how such coldness is possible.

“It is, after all, awkward, troublesome, to be involved in another person’s pain and despair,” he said. “Yet, for the person who is indifferent, his or her neighbor are of no consequence. And, therefore, their lives are meaningless. Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the other to an abstraction.”

By all appearances, Trump and his ilk can deliver pain and even death without losing a moment’s sleep. One wonders at how warped their sense of morality is. More than that, one must wonder how much longer most Americans can tolerate that in their leaders.