Vance, Trump and Tuberville ignore history and Christianity in making the claim

Eons ago, it seems, the late American cultural historian Warren I. Susman told undergraduates at Rutgers, including me, that in the U.S. we all are Protestants.

Of course, he didn’t mean that literally. Indeed, like 2 percent of the American population, Susman was Jewish. What he meant was that Americans of all faiths (or none) have been shaped by our history of Puritanism and the Protestant work ethic, topics he focused on in his work.

Pardon Susman, a colorful and entertaining lecturer, for occasional overstatement. In “Culture as History: The Transformation of American Society in the Twentieth Century” he wrote that “Mickey Mouse may in fact be more important to an understanding of the 1930s than Franklin Roosevelt.” The phrase triggered widespread tut-tutting among academics and critics, but it just reflected Susman’s view of “everyman” culture, not political history.

So, too, with his Protestantism comment.

Indeed, we’re not all marching into any of the dizzying variety of Protestant – or, more broadly, Christian – churches that populate the country. Today, only 62 percent of Americans call themselves Christians (including 40 percent Protestants and 19 percent Catholics), according to a Pew survey. Many of us – 29 percent – are unaffiliated (including atheists, agnostics and “nothings.”) Seven percent adhere to non-Christian faiths.

And yet, also today, plenty of folks seem to think the U.S. has long been a Christian nation — and they vow to do all they can to keep it that way.

“The only thing that has truly served as an anchor of the United States of America is that we have been, and by the grace of God, we always will be, a Christian nation,” Vice President JD Vance said to great applause at a pre-Christmas Turning Point USA gathering. “Christianity is America’s creed.”

The “only thing” that’s been an anchor? Not democracy? Not pluralism? Not a belief in equality? Not social mobility and opportunity?

And never mind that Vance’s wife, Usha Chilukuri Vance, is a Hindu. Moreover, don’t take note that the Vances are letting their three children choose their faith, even as they send them to a Catholic school. The vice president, who attended a Pentecostal church as a teen, converted to Catholicism in 2019.

To be sure, in true missionary style Vance wants Usha similarly to convert, something she has said isn’t on her agenda. That may make for intriguing dinner conversation, especially on visits to the in-laws.

But, while cultivating his own political prospects in his talk, Vance was echoing the comments of his boss, Donald J. Trump. At a Christmas tree lighting a few weeks before, the president departed from the usual broad and ecumenical presidential messages of the past, explicitly invoking Christian beliefs as fact.

“During this holy season, Christians everywhere rejoice at the Miracle in Bethlehem, more than 2,000 years ago when the Son of God, our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, came down from heaven to be with us,” Trump said. “Full of grace and truth, he brought the gift of God’s love into the world and the promise of salvation for every person and every nation…. Tonight, this beautiful evergreen tree glows bright in the dark and cold winter night and reminds us of the words of Gospel of John, in him was life and that life was the light of all mankind. Beautiful words. With the birth of Jesus, human history turned from night to day.”

Should one call it hypocrisy when a thrice-married often-philandering felon and business cheat makes such remarks? Should one call out the contradiction with Jesus’s teachings when he vindictively pursues his opponents by any means necessary (See James Comey, Letitia James, Mark Kelly)? Should one note the inconsistency when such a man orders up the summary executions of more than 100 people – some quite wantonly — on the unproven suspicion that they were ferrying drugs? Isn’t there a Christian (and Jewish) commandment against that sort of thing, not to mention American and international law?

Of course, Trumpists deftly used religion to win office and often invoke it to justify their actions. They have suckered plenty of folks with their pitches:

But historians more often point to the broad-minded approach the Founding Fathers took. The writers of our foundational national documents didn’t want to create a Christian nation, but rather one that tolerated many creeds.

“There were Christians among the Founders – no deists – but the key Founders who were most responsible for the founding documents (Declaration of Independence and Constitution) and who had the most influence were theistic rationalists,” argues Gregg Frazer, a professor of history & political studies at The Master’s University, a Christian university in California, with degrees from Claremont and California State University. “They did not intend to create a Christian nation. Not a single Founding Father made such a claim in any piece of private correspondence or any document. If they had, it would be blazoned above the entrances of countless Christian schools and we would all be inundated with emails repeating it.”

Frazer, a deacon in his community church who wrote “The Religious Beliefs of America’s Founders: Reason, Revelation, and Revolution,” holds that Christians “damage their witness by promoting historical inaccuracies” of the sort politicians such as Vance do. The Founders, he maintains, “were religious men who wanted religion – but not necessarily Christianity – to have significant influence in the public square.”

But many among them also wanted religion and government to be separate and a personal matter.

As President Thomas Jefferson wrote to a Baptist group in 1802: “Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

George Washington, an Anglican, was well aware of the diversity of religions in the United States, whether Christian or not. To a Jewish congregation in Rhode Island, he wrote, “It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.”

The Founders knew all too well about the diversity among religious groups and the tensions among them that had marked the early history of North America. As historians writing about George Washington’s Mount Vernon have recounted, in 1620 a group of Puritans arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts. Roman Catholics founded Maryland in 1634, and twenty years later Jews arrived in New York City.

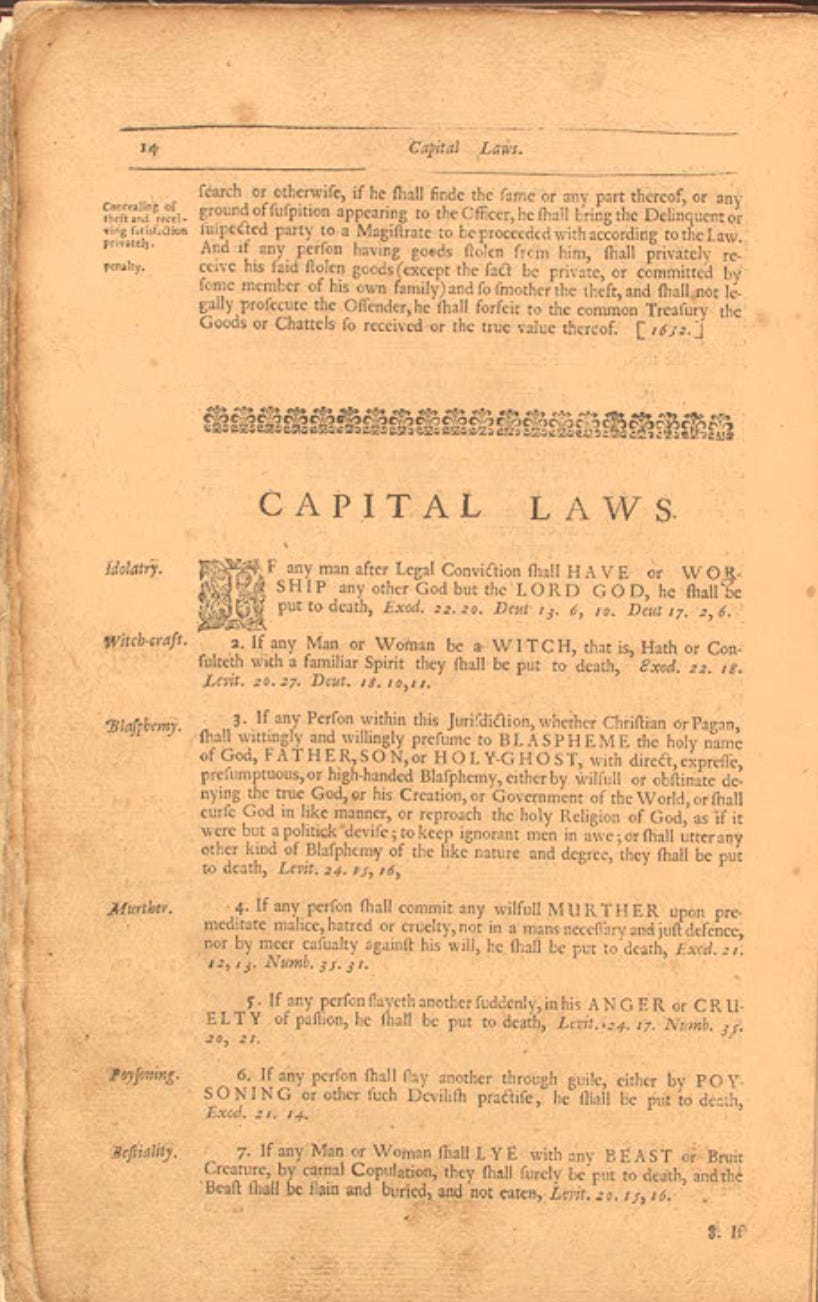

Each group was guided in civil matters by its own beliefs and many showed little respect for others. Puritans in New England based laws on the Bible, and only full church members were permitted to vote. While Catholicism thrived in Maryland in the 1630s, by the 1640s, Protestants took control and deported many Catholics, outlawing Roman Catholicism in 1654. Quakers were expelled from Massachusetts. Presbyterians and Baptists were banished from New England. In Virginia, Puritans and Quakers were barred.

It wasn’t until the so-called the Great Awakening in the 1740s that tolerance grew in some regions of the colonies. Given the potential fractiousness they faced, it’s no wonder that the Founders took refuge in a well-defined secularism, at least in common matters of government, despite objections by some fellow Americans.

“When the Constitution was submitted to the American public, ‘many pious people’ complained that the document had slighted God, for it contained ‘no recognition of his mercies to us . . . or even of his existence,’ according to The Library of Congress. “The Constitution was reticent about religion for two reasons: first, many delegates were committed federalists, who believed that the power to legislate on religion, if it existed at all, lay within the domain of the state, not the national, governments; second, the delegates believed that it would be a tactical mistake to introduce such a politically controversial issue as religion into the Constitution.”

Indeed, the library reports, the only “religious clause” in the document–the proscription of religious tests as qualifications for federal office in Article Six–was intended to defuse controversy by disarming potential critics who might claim religious discrimination in eligibility for public office.

Religious ideologues – like Vance – have tried to argue otherwise, insisting that Christianity is essentially mandated. “Thousands of pieces of evidence exist that demonstrate that America was founded as a Christian nation, and Holy Trinity v. United States is only one of the many pieces of that mosaic of historical truth,” argues one such source, the Christian Heritage Fellowship, citing an 1892 Supreme Court decision.

The fellowship points to the ruling written by Justice David Josiah Brewer, hardly a disinterested party since his father was a Congregational missionary. In it, he argued the “evidence,” culturally at least, was unmistakeable.

“Among other matters, note the following: the form of oath universally prevailing, concluding with an appeal to the Almighty; the custom of opening sessions of all deliberative bodies and most conventions with prayer; the prefatory words of all wills, ‘In the name of God, amen;’ the laws respecting the observance of the Sabbath, with the general cessation of all secular business, and the closing of courts, legislatures, and other similar public assemblies on that day; the churches and church organizations which abound in every city, town, and hamlet; the multitude of charitable organizations existing everywhere under Christian auspices; the gigantic missionary associations, with general support, and aiming to establish Christian missions in every quarter of the globe,” Brewer wrote. “These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.”

Well, since 1892 many of the oaths or affirmations we now use in the U.S. don’t invoke a deity. Plenty of businesses operate on Sundays. And, along with churches, we have many mosques, synagogues, temples and other institutions that speak to the breadth of American culture. We have leaders, such as Zohran Mamdani, taking their oaths of office on the Quran, not the Christian Bible.

Of course, we also have cultural fossils such as Alabama Sen. Tommy Tuberville, who declared on X, “The enemy is inside the gates,” on hearing about Mamdani’s swearing-in ceremony. In mid-December, the GOP lawmaker wrote on X, “Islam is not a religion. It’s a cult. Islamists aren’t here to assimilate. They’re here to conquer… We’ve got to SEND THEM HOME NOW or we’ll become the United Caliphate of America.”

Muslims account for 1 percent of the American population, according to Pew. This is about the same share as Buddhists. “United Caliphate,” really?

For the fossils, even single-digit percentages are intolerable. They would have fit in well with the “pious people” who objected to the absence of Divine references in our country’s founding documents.

While the likes of Vance, Tuberville and Trump are prominent now, it may be that their time running things could prove short. That is, of course, if enough moral people — G-d-fearing and otherwise — rebel against their hypocrisy and narrow-mindedness. Another thing historian Susman was mindful of was that one of the few constants in America is change, sometimes for the better.