Athletes, academics and politicians have trouble letting go

After Lindsey Vonn wiped out in the downhill competition in the Olympics, suffering barely endurable pain from a complex tibia fracture in her left leg, her father made clear his preferences for her athletic future.

“She’s 41 years old and this is the end of her career,” former ski racer Alan Kildow told The Associated Press. “There will be no more ski races for Lindsey Vonn, as long as I have anything to say about it.”

From his lips to G-d’s ear, we might say. Far too often, athletes, academics and, particularly, politicians, just stick around too long. They can’t let go, it seems, even when their bodies – and perhaps, their minds – should compel them to do otherwise.

Consider Tom Brady, who played professional football for 23 seasons. Unable to say sayonara, at age 45 the longtime New England Patriots star jumped to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 2022. That led to his first losing season, with an 8-9 record and a playoffs washout.

A writer at SBNATION was unflinching about the faded star. “Tom Brady’s final season was a huge waste of time for everyone involved: It was a horrible, terrible, no good, very bad year” was the headline.

Years earlier, there was Muhammad Ali, who quit boxing at 39 in 1981. After two decades in the ring, Parkinson’s Disease ultimately delivered a knockout to “The Greatest.” Ali’s pace and speech began to slow down in the late 1970s, but he wasn’t formally diagnosed with Parkinson’s until 1984, three years after he had left professional boxing, as TheSportster recorded

In academia, many professors linger well past 65. Some may be fine well into their 80s, but it’s all too likely that they grow out of touch with progress in their fields, as well as the cultural and social world their students inhabit. They also clog up the talent pipeline, keeping younger – and more diverse – potential faculty out.

“Nationally, aging faculty remain overwhelmingly white, and the diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives that swept through elite universities in the 2010s largely failed to dislodge them,” an opinion writer observed in The Harvard Crimson. “As the writer Jacob Savage demonstrated in a viral essay in December, efforts to remedy elite institutions’ lack of racial diversity fell not upon older white men, but upon incoming hires.”

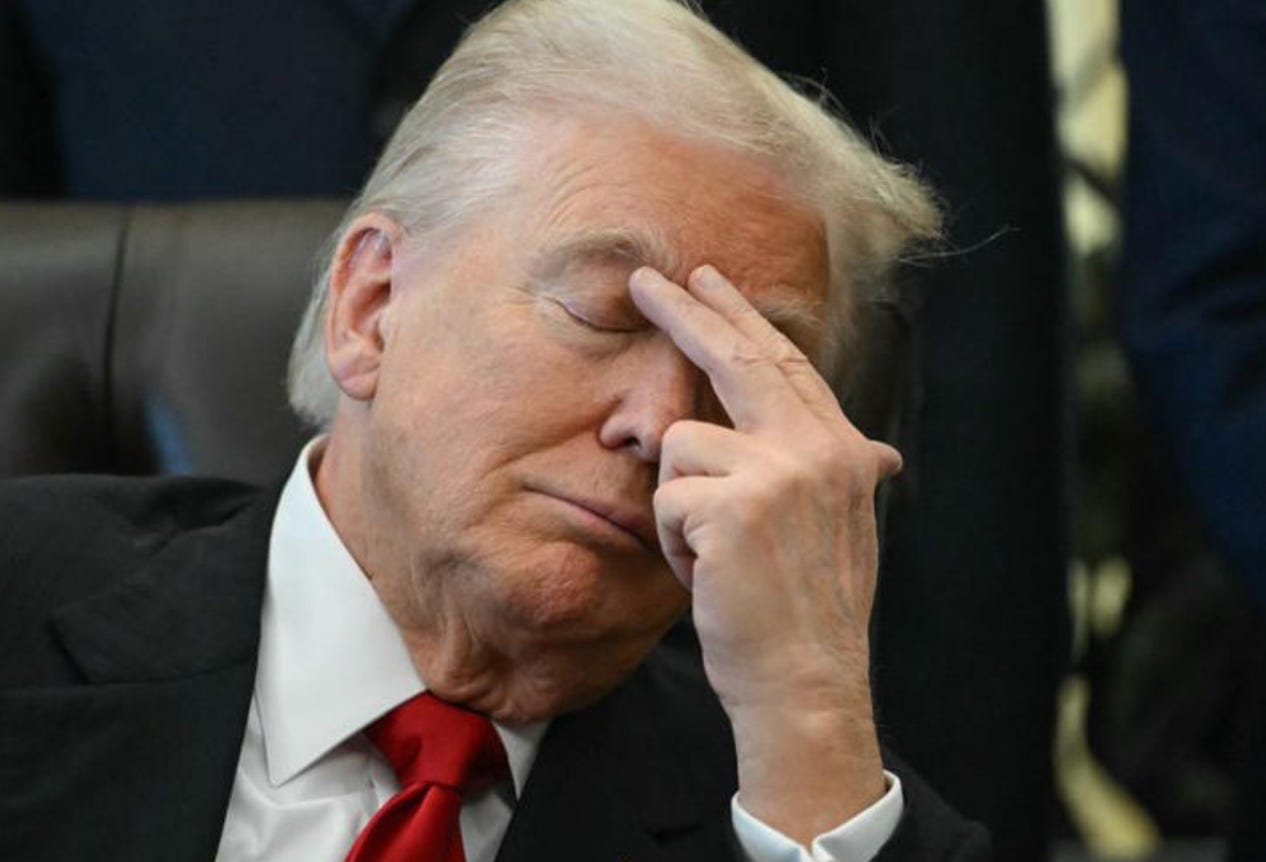

Of course, politicians are among the worst for being unable to hang it up. The infirmities of age that afflicted Joseph R. Biden, in office until age 82, and Donald J. Trump, soon to turn 80, are well-known. Indeed, had Biden quit the game earlier, we all might have been spared the many griefs inflicted on us by the increasingly doddering and rambling Trump.

Trump is showing signs of aging in public and private, The Wall Street Journal has reported. He has struggled to keep his eyes open during several televised events, and some people close to him have said he at times strains to hear. (Trump denied having a hearing problem and said he closes his eyes for relaxation.) Biden’s age-related collapse in 2024 damaged the Democratic Party in ways it is still working to repair.

As the newspaper also reported, Rahm Emanuel, a 66-year-old Democrat and Washington veteran, recently called for a mandatory retirement age of 75 for presidents, cabinet officials, members of Congress and federal judges. The former congressman, White House chief of staff, Chicago mayor and potential White House contender said that should also apply to him, should he ever return to a major Washington job.

According to The Harvard Crimson opinion writer, Alex Bronzini-Vender, in 2025, roughly 37 percent of congressional Democrats were 65 or older, along with 29 percent of congressional Republicans. In 2024, nearly 18 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs were aged 65 or older. And in 2020, about 14 percent of American lawyers and 24 percent of state judges “had crossed the same threshold.”

Twenty-four members of Congress are 80 or older, according to NBC News. In total, this Congress is the third-oldest in U.S. history, with an average age of 58.9 years at the start of this session one year ago. The median age in the U.S. is 39.1.

Of course, the threshold for packing it in can vary by field. Skiing for fun is something folks in their 80s do, but perhaps not rushing down mountains at speeds topping 70 miles an hour.

The longtime champion Vonn was famous, of course for retiring in 2019 after a slew of injuries. She underwent three surgeries between the 2017-18 and 2018-19 seasons after tearing her LCL with three tibial plateau fractures in her left leg. She also missed the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics due to injury, after winning gold at the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics despite fighting through an “excruciating” bone bruise in her leg.

After she underwent surgery for a partial knee replacement in 2024, she felt healthy, prompting her to leave retirement. Even after she tore her left ACL in training a week before her disastrous run on Feb. 8, she insisted on competing.

“But being here today, being around all of this Olympic spirit has me so excited about the potential and how I could hopefully close my career in a way that is really based on what I want to do,” she said before the race. “I retired in 2019 because my body said no more, not because I didn’t want to continue racing. I feel like this could be an incredible moment to end the chapter, this chapter of my life, and move forward in a really exciting and peaceful way.”

Skiing, of course, had been Vonn’s life. Her father and grandfather taught her starting at age 3 in Minnesota. She competed in her first races at 7 and took part in international competitions at 9, took part in her first Olympic Games at 17 and kept competing – and usually winning — for decades.

And the problem with that sort of commitment – not uncommon in sports or in some other fields with nearly lifelong obligations – is that one has to either discover or reinvent oneself when the playing field is no longer available. The question arises: “Who am I, if not a top-level skier or quarterback or professor or journalist or politician?”

Consider George Koonce, a former NFL player who attempted suicide after his playing days with the Green Bay Packers and Seattle Seahawks ended. Speaking on the point in a 2012 ESPN piece, he said: “Football becomes your identity. Your family buys into it, your friends buy into it, the alums from your college buy into it. And then it is gone. You are gone.”

But Koonce decided not to be “gone.” He earned degrees in sports management and administration (the latter a doctorate), and filled important positions at Marquette University, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Marian University. He coauthored the book “Is There Life After Football?:Surviving the NFL.”

Even as athletics, academics and politics may well shape a person’s life and career, there comes a time when they need to look to other things – perhaps in related areas, perhaps not. In hindsight, it seems that time should have come far sooner for Vonn. One wonders whether her father and others in her life might have delivered that message earlier, sparing her the globally broadcast anguish she suffered.