What is it that drives winners? For some, it is living up to expectations set by demanding teachers, coaches or parents. For others, it’s simple “self-fulfillment,” as the cliché-peddlers would have it. For still others – perhaps more of us than would care to admit it – outward success is an attempt to fill deep emotional holes left by childhood deprivations.

What is it that drives winners? For some, it is living up to expectations set by demanding teachers, coaches or parents. For others, it’s simple “self-fulfillment,” as the cliché-peddlers would have it. For still others – perhaps more of us than would care to admit it – outward success is an attempt to fill deep emotional holes left by childhood deprivations.

A few things came together in the past week to raise this question anew for me. Nationally, there was Newt Gingrich’s surprising success in South Carolina, a victory that came about just after a revealing 1995 profile in Vanity Fair gained renewed life on the Net. In the piece Gail Sheehy sought to fathom the hungers that drive Newt, someone abandoned by a father, tormented by an angry stepfather and smothered by a manic-depressive mother. How can such trauma not sear one for life? Today, we know that Gingrich’s canyon-deep needs have proved too great for three wives to fill. Nothing less than the presidency might come close to sating him (and one doubts that will be enough).

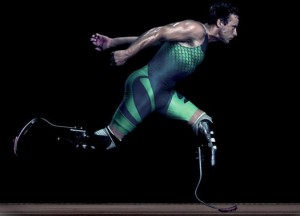

Then there was the cover story in the New York Times Magazine about Oscar Pistorius, the would-be Olympian. The “fastest man on no legs,” he runs with prostheses since both his legs were amputated below the knee as an 11-month-old because of a birth defect. That’s not all he’s had to deal with: the runner’s parents divorced when he was six and his mother died when he was 15. He is estranged from his father. “Everyone has setbacks,” Pistorius told author Michael Sokolove, shrugging off his challenges in jock-like manner. “I’m not different. I happen to have no legs.”

Then there was the cover story in the New York Times Magazine about Oscar Pistorius, the would-be Olympian. The “fastest man on no legs,” he runs with prostheses since both his legs were amputated below the knee as an 11-month-old because of a birth defect. That’s not all he’s had to deal with: the runner’s parents divorced when he was six and his mother died when he was 15. He is estranged from his father. “Everyone has setbacks,” Pistorius told author Michael Sokolove, shrugging off his challenges in jock-like manner. “I’m not different. I happen to have no legs.”

Closer to home for me, there were the autobiographies my Journalism 202 students wrote. As always, too many of their tales were troubling. Despite their fresh faces and youthful eagerness, some are hauling a lot of baggage for kids barely out of their teens (some perhaps still in them). Divorces, infidelity and alcoholism at home. Dread diseases in those close to them. One told of struggling as a single mother in high school in a religious rural community.

Will these kids overcome the bad hands life has dealt them? Will they, like Gingrich, Pistorius and plenty of others, figure out how to turn shortcomings into sources of strength? Can satisfying their cravings lead them to successes in journalism or whatever field opens for them?

There are heartening signs. Take the single mom, for instance. She was the “moral symbol” of her Christian school with a laundry list of accomplishments from church group leadership to sports and student-council activities. Then pregnancy got her kicked out. (So much for Christian charity.) Today, though, she calls her 2½-year-old son her “precious little gift from God.” She says he’s the source of her inspiration to pursue a broadcasting career.

There’s the young woman whose life has been scarred – three times – by divorce. Her mom divorced twice before she was six, a third time when she was in high school. Through it all, she threw herself into athletics, band and academics. Today, she’s making her mark in college sports. “My past has built me into a strong, tenacious woman,” she wrote. “I have only scratched the surface the surface of what is going to be an amazing life.”

Then there’s the young man who told, unblinkingly, of his mother’s failings. When he was 10, he wrote (in the third person), she “cheated on his father with her coworker.” She often came home late and drunk. She and the boy’s father split and eventually the father remarried, recreating a family. The student, who excelled in high school theater, choir and speech, told of how he’s following a passion for telling stories. “For now, I’m living my life the way I want to lead it,” he wrote.

Then there’s the young man who told, unblinkingly, of his mother’s failings. When he was 10, he wrote (in the third person), she “cheated on his father with her coworker.” She often came home late and drunk. She and the boy’s father split and eventually the father remarried, recreating a family. The student, who excelled in high school theater, choir and speech, told of how he’s following a passion for telling stories. “For now, I’m living my life the way I want to lead it,” he wrote.

I’m encouraged by the determination these kids feel. They seem to know that the same things that nearly hobbled them are the things that can put steel in their spines. There’s no self-pity in their tales, though there is, of course, hunger. There’s a need for recognition, a need for someone to listen.

Such needs are not bad things in a journalist. Richard Behar, an award-winning investigative journalist for Time, Forbes and other publications, came to UNL a while ago and told of his personal history. He grew up as a ward of the state of New York, knocking around its foster-care system. Clearly, in sharing that story, he was suggesting the challenges he dealt with were responsible, in part, for the successes he has had.

Journalists, after all, want to be heard. My longtime editor at BusinessWeek, Steve Shepard, added bylines to the magazine years ago, understanding that recognition drives writers to do their best work. For years, the philosophy had been that magazine writing was a group effort. That’s still true, but he felt – rightly – that pursuit of the limelight was too powerful to ignore. What journalist worth his or her salt doesn’t want a cover story or front-page piece bearing his or her name?

In politicians (and perhaps journalists), overwhelming hungers can be dangerous, of course. Insatiable needs nearly derailed the otherwise successful presidency of Bill Clinton. They crushed the presidency of the much-tortured Richard Nixon. Soon, voters may have to judge whether Gingrich’s psychological shortcomings will make him a good or impossible president. Oddly enough, they could face a choice between him and President Obama, a man shaped in large part by the lack of a father. Great needs may drive great winners, but an honest journalist will tell you they still they remain great needs.